Why do serial entrepreneurs keep jumping back in? What things might you learn the third, fourth, or fifth time around?

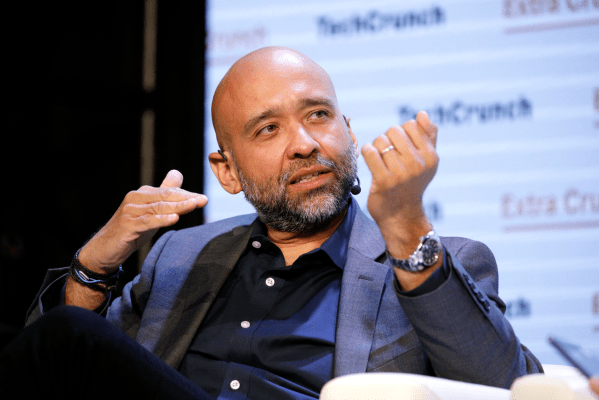

To find out, Extra Crunch Managing Editor Eric Eldon spoke to Drift CEO and founder David Cancel at TechCrunch Disrupt San Francisco. Cancel has spent more than 20 years founding SaaS companies, with exits including Compete (acquired by TNS), Lookery (Acknowledge), Ghostery (Evidon), and Performable (Hubspot.)

In their thirty-minute conversation, they cover everything from finding your first customers, to what he’s seen change over the last two decades in the industry, to why he’s willing to cut a check to employees who want to leave. Rather watch them talk for yourself? We’ve embedded a video of their chat at the end of this article.

To find what people really want, ask for money — any money.

One thing Cancel says he’s learned over the years: when you’re just getting started, you need to charge for your product right off the bat because you never know how someone really feels about a product until you ask for money.

“If you’re creating a paid-for product, you have to start charging from day one,” he says.

He outlines an experiment he calls the ‘dollar test,’ where if someone seems interested in a product before it’s even available, he’ll promise them lifetime access if they’ll hand over whatever’s in their pocket — be it a dollar, ten, twenty, whatever.

“What it teaches the entrepreneur is that most of the people who will tell you that they love this thing will not give you a dollar,” actionable information that can save time, money and stress. The dollar test “shortcuts things; most people will end up spending so much time coming back to you because you keep telling [them] you love it, because you’re a nice person and you don’t want to hurt [their] feelings.”

Cancel also uses this approach after a product launches, using it to gauge which new feature requests customers find most important.

“They’d say ‘I love your product, but it doesn’t do X, Y, or Z. My company is special, we need X, Y, or Z feature.'”

“Let’s say they were paying us $5,000 a month. I’d say, ‘it’s only going to be $20 more a month, then we’re going to build it for you and you’ll be the first ones to have it.'”

“What would happen, almost every single time, is there would be this awkward pause. They’d say ‘I have to go talk to my manager, I need to go talk to someone, I’ll get right back to you,'” he said, adding “Almost every single time that person continued to be a customer and never asked for that feature again.”

“When it’s free to ask for anything,” says David, “people will just keep asking.”

Letting people go isn’t always a bad thing

If someone asks David for a recommendation on an engineer, he’s willing to recommend his own employees.

His reasoning is twofold; on one side, it means he knows his teams are made up of people who want to be there; on the other, it means employees know he’s looking out for them.

“I want people on the team who want to be on the team. If people ask me, ‘hey, do you know a really great engineer who does X, Y, Z?'” I say ‘Eric does, and Eric’s on my team.’ I’m like, you should talk to him. And if Eric wants to go, he should go, because we only want people who actually [want] to be there. Then that person knows that I’m looking out for the best interests of them, for them — and even if they go, we may end up working together again later.”

Similarly, if an employee says they want to leave and start their own company, David says he’s often the first to write a check:

“We would attract, in the early days, people who wanted to learn how to start their own company. One of the things I would say, and I still say to everyone: Look, if you come on board, and work with us for some days, if you want to leave at any point and start a company, myself and my co-founder Elias will be the first checks in whatever you want to start, no questions asked.”

“And so we have done that for companies in Boston, companies in San Francisco, companies all over the place. And we continue to do that.”

For finding customers and employees, he turns to LinkedIn

Thanks to recruiter spam and “work anniversary” notifications, LinkedIn tends to be the butt of a lot of jokes — but Cancel says, used right, it’s still quite valuable.

“We built a lot of marketing within LinkedIn, which I think is a place that I would advise people to go spend time on now. You can find your buyers, you can find the people that you recruit.”

“It’s amazing, the performance we have on LinkedIn,” he says. “Even today, it’s insane. Some of the stuff they added — once they added video, and live [broadcasting] recently, all that stuff — you have the audience that you want to address, and you have the ability to build a [network of people] who are your future buyers, or future people who you want to join the company.”

“It’s way more effective than Facebook, Instagram, or any of that stuff for a largely B2B audience,” he adds.

What’s changed?

In the twenty-two years he’s been in tech and SaaS, David says he’s seen the industry go through three phases, which he calls the “Thomas Edison,” “Henry Ford,” and “Proctor & Gamble” phases.

“In the first generation of SaaS companies — which was like, the late 90s, early 2000s — we had a decade of companies that were really in this phase that I call the ‘Edison’ phase,” he says. “In that world, when we were creating companies, the fact that we could even create the technology itself, and that we could hide behind patents, or we could hide behind trade secrets and all that stuff… that was the competitive moat that we had in there.”

“It was more about pure invention in that phase,” he notes. “That’s why I call it the Thomas Edison phase.”

Next came what he calls the “Henry Ford” phase, which he says started around 2007, comparing it to the automaker who popularized the production line. It was no longer just about being able to build a thing, but finding the best ways to build a thing — and how to know what was really working.

“It was about factory-building, right? The technology was no longer the moat, because everyone could copy technology.”

“We had open source. We had ways to understand. We had Google — now we could search for things on Stack Exchange. We could copy thing easily from a code standpoint; the real differentiator, in that decade, was go-to market metrics.”

“How do you measure this stuff? How do you build the factory? Was it horizontal SaaS? Vertical SaaS? Is it freemium? We didn’t know what freemium was.”

“Was it sales reps, was it inside sales, was it field sales — or was it a combination of those things?” he asks. “There was no way to find this information — so that was the moat.”

Now, a few years into founding the automated marketing platform Drift, David says we’re now in the “Procter and Gamble” phase, in which there are a thousand competitors for every offering. Now that customers have a thousand choices, it’s all about building a brand.

“Everybody knows what the metrics look like. Everybody knows how to build the technology. Those moats are gone. So what’s the next moat? We believe it’s a brand moat.”

“We’re effectively selling a commodity. The power moves all the way to the customer at that point; if you have a thousand alternatives for marketing automation, you have all the power. It’s not 20 years ago, where there was one vendor or two vendors that you had to sit through a sales pitch for. You have all the information, and it’s free. You can go to G2 Crowd, you could go to TrustPilot, you can go anywhere and read everything you ever wanted to know about these products. So that information moat is gone.”

“So that’s the phase I think we’re in right now,” he adds. “We’re seeing the number of competitors in every given market accelerating. They’re not holding steady, and now we’re competing truly on a global stage. Even in marketing itself, we have, you know, 7000 alternatives for that dollar.”

Why he keeps starting companies

Starting a company is hard. It’s stressful, the hours are endless, and successes are the exceptions. It’s not something that most people ever do — much less something that people do time and time again.

“If you start one company, it’s excusable because you were naive — you didn’t know. You start two, it’s questionable. You start three or more, you’re like… certifiable,” he told the Disrupt audience. “Like there’s something wrong. There’s like… there’s some deep psychological need that you’re trying to fill.”

So why keep rolling the dice, even after multiple successful exits? “I feel like I still have something to prove,” he says.

After Drift, though, he says he’s done. “I will never start another company again. This is the last one, I’ll just make it last as long as possible.”

His advice to founders

Asked to share one piece of advice with the founders in the audience, Cancel offered up a straightforward concept: be open to learning from others.

“I learned most things by brute force and pain by just trying to learn on my own. [But] these lessons are out here, including at events like this… listen, actually listen, to a lot of these things and save yourself the heartache,” says Cancel. “Now I read a lot, and I have mentors and role models and a lot of people that I talk to, because I don’t want to keep learning everything through brute force and pain.”