As I wrote for TechCrunch recently, immigration is not an issue always associated with tech — not even when thinking about the ethics of technology, as I do here.

So when I was moved to tears a few weeks ago, on seeing footage of groups of 18 Jewish protestors link arms to block the entrances to ICE detention facilities, bearing banners reading “Never Again” in reference to the Holocaust — these mostly young women risking their physical freedom and safety to try to help the children this country’s immigration service is placing in concentration camps today, one of my first thoughts was: I can’t cover that for my TechCrunch column. It’s about ethics of course, but not about tech.

It turns out that wasn’t correct. Immigration is a tech issue. In fact, companies such as Wayfair (furniture), Amazon (web services), and Palantir (the software used to track undocumented immigrants) have borne heavy criticism for their support of and partnership with ICE’s efforts under the current administration.

And as I discussed earlier this month with Jaclyn Friedman, a leading sex ethics expert and one of the ICE protestors arrested in a major demonstration in Boston, social media technology has been instrumental in building and amplifying those protests.

But there’s more. IBM, for example, has an unfortunate and dark history of support for Nazi extermination efforts, and many recent commentators have drawn parallels between what IBM did during the Holocaust and what companies like Palantir are beginning to do now.

I say “companies,” plural, with intention: immigrant advocacy organization Mijente recently released news that Anduril, the company founded by Palmer Luckey and composed of Palantir veterans, now has a $13.5 million contract with the Marine corps for their autonomous surveillance “Lattice” towers at four different USMC bases, including one border base. Documents procured via the Freedom of Information Act show the Marines mention “the intrusion dilemma” in their justification for choosing Anduril.

So now it seems the kinds of surveillance tech we know are badly biased at best — facial recognition? Panopticon-style observation? Algorithms of various other kinds — will be put to work by the most powerful fighting force ever designed, for expanded intervention into our immigration system.

Will the Silicon Valley elite say “no”? To what extent will new protests emerge, where the sorts of people likely to be reading this writing might draw a line and make work more difficult for their peers at places like Anduril?

Maybe the problem, however, is that most of us think of immigration ethics as an issue that might touch on a small handful of particularly libertarian-leaning tech companies, but surely it doesn’t go beyond that, right? Can’t the average techie in San Francisco or elsewhere safely and accurately say these problems don’t actually implicate them?

Turns out that’s not right either.

Which is why I had to speak this week with Cornell University historian Louis Hyman. Hyman is a Professor at Cornell’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations, and Director of the ILR’s Institute for Workplace Studies, in New York. In our conversation, Hyman and I dig into Silicon Valley’s history with labor rights, startup work structures and the role of immigration in the US tech ecosystem. Beyond that, I’ll let him introduce himself and his extraordinary work, below.

Greg Epstein: I discovered your work via a piece you wrote in the Washington Post, which drew from your 2018 book, Temp: How American Work, American Business, and the American Dream Became Temporary. In it, you wrote, “Undocumented workers have been foundational to the rise of our most vaunted hub of innovative capitalism: Silicon Valley.”

And in the book itself, you write at one point, “To understand the electronics industry is simple: every time someone says “robot,” simply picture a woman of color. Instead of self-aware robots, workers—all women, mostly immigrants, sometimes undocumented—hunched over tables with magnifying glasses assembling parts, sometimes on a factory line and sometimes on a kitchen table. Though it paid a lot of lip service to automation, Silicon Valley truly relied upon a transient workforce of workers outside of traditional labor relations.”

Can you just give us a brief introduction to the historical context behind these kinds of comments?

Louis Hyman: Sure. One of the key questions all of us ask is why is there only one Silicon Valley. There are different answers for that.

There is Stanford. [Another] answer that’s often offered is venture capital. Another answer, as Margaret O’Mara argues in her new book, is the lack of no-compete clauses.

Epstein: You subtweeted The Wall Street Journal’s Christopher Mims about this last year. He was referencing some of these ideas about why Silicon Valley is in California and not Boston.

Hyman: I don’t remember that because I have a terrible memory, but all the different kinds of answers really start from the top. They start with [typically] male engineer technologists. When we talk about Silicon Valley we say “technology,” not “industry.”

When you reframe Silicon Valley, reframe electronics and software as an industry, it actually looks quite different. Because [when] you say “industry,” you think, who are the workers? Who’s making these things? And that’s when the story really quite quickly falls out of the archives.

The story of Silicon Valley, which is different than the story of Boston, is that there has long been a large pool of migrant labor, legal and undocumented labor, in the groves there, right? Before there was Silicon Valley, it was a place where oranges were grown.

And if you think about the other great hub of technology and electronics, which is Texas, that’s also true. So it’s part of what, obviously correlation is not causation, but so when I started to think about that, I said, “Let me go look in the archives and see what these businesses actually were doing with the people who worked for them.”

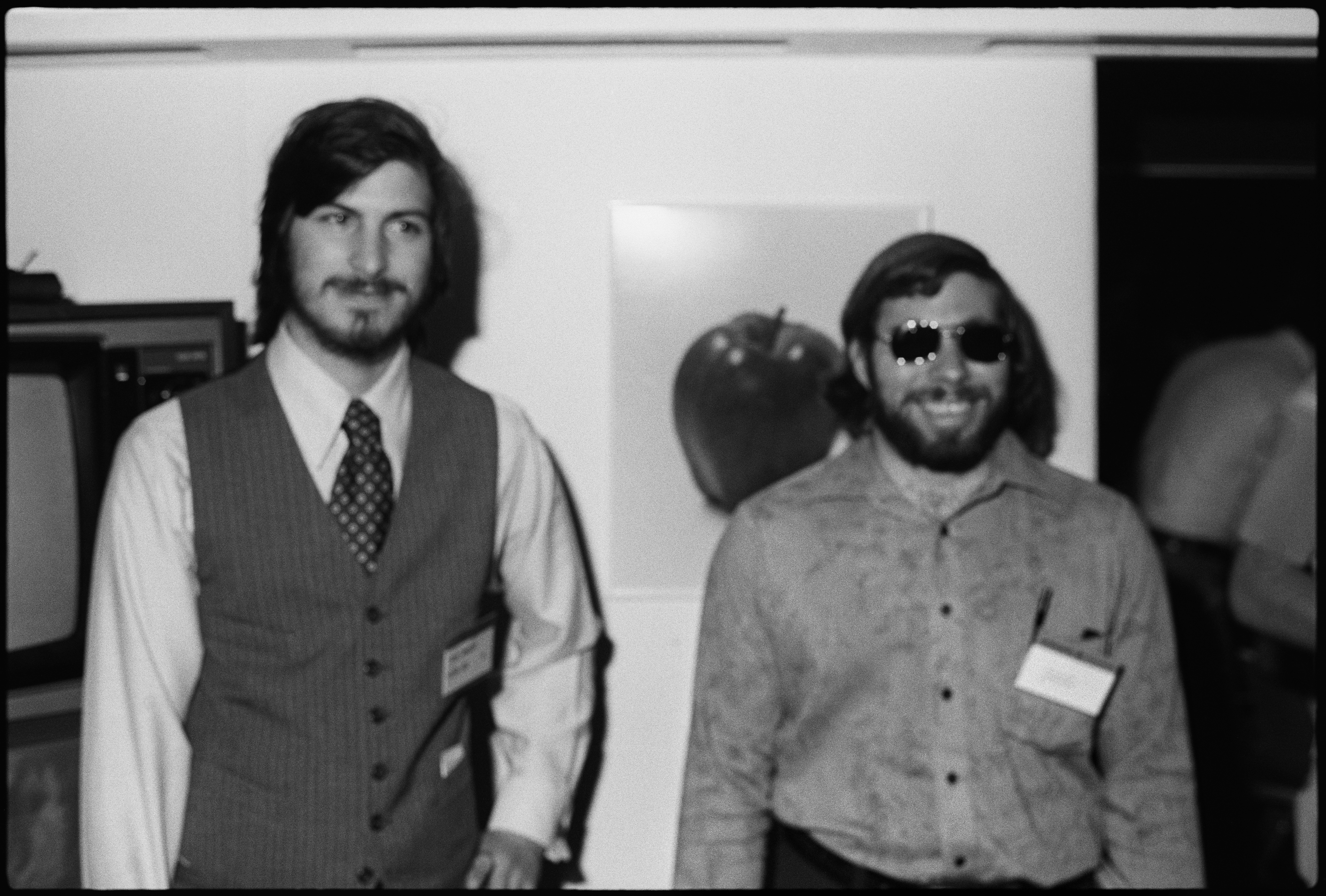

When you go into the Apple archives, the HP archives, and the INS archives, you see a very different story than the one that we’re told when we just talk about Steve Jobs and Woz.

Epstein: For those who are not academics: what does that look like, to “go into their archives?” What did you actually have to do to figure out the role of immigration in these companies?

Hyman: What makes historians historians is going to archives. A lot of things are available online these days and that’s made for a revolution in the kinds of histories we can write, but many things are still on paper and you have to find them.

I visited many different archives. Some of them are public. You can go to the Apple archives at Stanford. Or you can go to the National Archives and some of them are public, but hidden in plain sight.

So one of the issues with the history of the Border Patrol and INS, which is the precursor to ICE, is that their papers end in the late 1950s in the National Archives. As far as I know, I’m the first historian to use the internal library of ICE, of INS, in writing.

And that story really changes the history of undocumented labor in the 60s, 70s and 80s. You can see in that archive the story not of agricultural labor, but industrial labor which is, of course, what electronics is.

Hyman: Another key archive for this stuff was also interviews. In the early 1980s, there was a group of sort of counter-culturalists who wrote zines which were sort of a paper version of blogs, for people who don’t remember zines. And I did lots of interviews of people who were part of that, for a zine called “Processed World” talking about what they saw in San Francisco and Silicon Valley in the early 80s.

Epstein: I’m going to check out that zine.

Hyman: It’s awesome, and actually available online.

Epstein: What you then found was this tremendous reliance on undocumented immigrants, and you emphasize the role of women of color in building Silicon Valley.

We’re currently having this nationwide conversation about “Donald Trump versus The Squad”, and what you’re saying is before we had visible, brilliant women of color congresswomen, we had women of color who were creating our modern world through their unheralded work in technology. Could you tell some of that story?

Hyman: Sure. What I tried to do in the book is, write the first labor history of the Macintosh. I mean, how many books have been written about the history of Apple and the Macintosh and Steve Jobs? I thought to myself, “How does a computer actually get built?”

In Silicon Valley, there is a small team of engineers, nearly all white, all men more or less and then beneath that is the production. That production has been left out of the story.

So in 1984 Apple opens the first Macintosh plant and it’s right across the street from the NUMMI plant which was meant to be this Toyota/General Motors joint project to reinvigorate American auto manufacturing. What’s interesting is that that story is told a lot in industrial history, but the story of the Macintosh is not and they’re right across the street from each other.

In [Apple’s] factory the headlines all read “Robots building robots. Machines building machines.” This is an important part of the ideology of Silicon Valley: a disposable workforce.

People don’t matter. It’s an automated future. It signals this sort of post-scarcity utopia, like Star Trek, and this is deeply influential to how we make the very unequal present palatable to people who otherwise would really strongly object to it.

Anyway, if you look in that factory, which is what I did in the archives, you can see the faces and the names of the people who were actually not robots. They’re people, and they’re mostly women of color who are putting together the Macintosh, who are Asian immigrants, who are Latina immigrants.

Legal in that facility, but then beneath that — and this is true not just for Apple, but for IBM, for Seagate, for Ampex, for all the major manufacturers of Silicon Valley in the 80s — beneath that is a layer of subcontracted production.

This is important because when you subcontract out, you don’t take legal responsibility for the workers, you don’t take legal responsibility for the ways in which those products are produced. And a lot of the ways in which these components are subcontracted for are very toxic and very labor-intensive.

The toxic work gets subcontracted out to a rotating panoply of Quonset huts, which are ad hoc buildings filled with open trashcans, full of chemicals where different electronics components are dipped and processed with fumes and toxic effluvia, by men who don’t speak English, by men who are not part of the official workforce count. And this is essential to the operations.

The intermediate world between those subcontractors and the main assemblers are temporary workers that are white and native-born, who shuttle these materials back and forth. Again, so the companies don’t have to take responsibility.

[There is] another part of that network — which investigators in the 1980s knew, so a lot of the story is known by people who have been paying attention. But a lot of us have not. And it’s something we don’t want to see — is the way in which components are assembled together.

[Assembly] is done through kitchen labor by Asian immigrants, especially Vietnamese immigrants and, again, Latina immigrants and their children. So their children are all around a table like cigar rollers, only this is the 1980s and they are putting together components.

And investigators basically threw up their hands. State regulators threw up their hands and said, “Look, we can’t regulate this. It’s too hard. We can’t find them all.”

It’s easy to say that, because there’s so much incentive to look the other way. This is the new growth industry of the 80s.

So that’s the story. And you see the same kind of subcontracted illegal labor when so-called tech moves to Texas. Not at Apple, but in many other kinds of companies, there were undocumented workers, again, mostly women, officially working in these factories.

This is where the INS archive really comes into play because you can see in the INS investigations from the San Jose field office that this undocumented workforce of women of color is essential to the operation of factories in Silicon Valley.

Epstein: Can you walk me through the process of reading the archives and deriving that information?

Hyman: It is right there on the page. Various people, talking about how they want to get rid of these illegals and how important it is for the American economy to do so. And there is a tension [in] treating undocumented people as illegal.

Who should you prosecute? The people who are working there? The employers? Our intuition as moral people is to prosecute the employers. And I basically show why that doesn’t work again and again, as people try to do that.

Epstein: Can you clarify why that doesn’t work again and again? Because the industries are increasingly powerful financially and/or politically, so employers are given a free pass? Or other reasons?

Hyman: Historically, whenever these attempts are made to prosecute employers, the government simply does not enforce the law. It is… shocking. A more satisfying solution to illegal employment would be penalizing the employers who seek to subvert our laws.

This plan was first tried, and failed, in California in the early 1970s. In California, in the decade after its passage, no one was prosecuted under the law. Gaylord Grove of the San Diego Office of the Labor Commission told an interviewer in 1982, “Oh, we don’t enforce that law…It’s a dead law.”

[And when] the California law failed, its failure went unnoticed. The logic of employer sanctions, with its moral high-ground, became a model for national policy, starting with President Carter in 1977. Meanwhile, of course, undocumented laborers were still being captured at electronics factories across the state and deported, with no consequence for the companies themselves.

And so part of the story in the book is that failed legislative and regulatory history and it’s disappointing that this basically happens again and again and nothing changes for the actual workers who are rounded up and put in detention facilities.

Epstein: What I think I’m hearing is a story about an emerging industry that has radically transformed all of our lives, essentially only because of women of color growing their fingernails long in order to be able to handle delicate materials, and then also many men of color transporting toxic and dangerous materials.

Without all of that, there would not have been these products that glamorously came onto our scene as economical and fancy and trendy and helpful. At least not anywhere near at the price that they were at.

And we then herald the people who thought this arrangement up as geniuses, while as for the people who made it possible, their legacy seems to me to be that now people in their position or who may be coming to this country to try to get into that position are not only being exposed to dangerous situations or maybe being detained or maybe being subject to racism, but now they’re literally being stripped in many, many cases from their children. They’re being subject to abuse. They’re being put into concentration camp-like conditions.

Do you want to dispute or nuance any of what I just shared?

Hyman: No. I mean it’s really straightforward. There’s no secret here. That is exactly what has happened and that’s exactly what is happening.

One might say, “Well, that was hardware. Hardware is different than software. Software is different. Software doesn’t create toxic work environments. Software doesn’t do this. Software doesn’t do that.”

That’s not true either. So many of the ways in which our machine learning is being trained, because you have to train machine learning algorithms, [are] by exporting visual information to basically, again, women of color, mostly in Asia, who are then training the algorithms.

Imagine if your job all day was to watch the worst most violent, most degrading, most horrifying pornography on the internet. That’s what these people do all day.

There’s this dodge where they say, “Oh, it’s the algorithm. It’s the machine. It’s automated.” But it’s actually just poorly paid women of color who are doing it.

And again, they’re saying, “Well, this is a transitional workforce so it doesn’t matter how we treat them, because in the future, once we have machine learning algorithms, we can automate these people away.” Just erasure.

It’s about who counts and who doesn’t, [who] deserves to be part of the social compact and [who gets] pushed outside of it. And in that way, it’s exactly the conversation we’re having today about the border: “Who is American and who gets to have American lives?”

Epstein: You’re raising the issue of “ghost work,” a term coined by Mary Gray, an anthropologist at Microsoft and the Harvard Berkman Center, and Siddharth Suri, a computer scientist, to refer to all the invisible and erased human work required to make tech what it is today.

Thankfully the issue is starting to get more attention: UCLA scholar Sarah Roberts has a very good new book, “Behind the Screen,” and there is a harrowing new documentary called “The Cleaners,” about all the content moderators who are suffering incredible mental health stress and strain because of the online content at companies like Facebook and YouTube right now. I hear you as putting all that in historical context.

What I take from your comments is that and saying that the content moderators who are sometimes literally dying from the stress and strain of moderating online tech are the direct successor of the kind of ghost work that was done by migrants to this country when Silicon Valley still needed to be physically built up and assembled.

Is there really a direct trajectory where these two things can be considered part and parcel of the same phenomenon?

Hyman: That’s exactly what I argue in [Temp]. Exactly. This is in the DNA of Silicon Valley, both as an ideology and a practice. Outsource, subcontract to people that then don’t matter.

The idea that you can have this world of “tech” without disposable people, I don’t know if it’s possible, but I know it never happens. All this wealth is being built on the backs of people who are considered disposable and that’s about race, it’s about gender, it’s about nationality. [It’s about] where we draw the lines between who matters and who doesn’t.

Epstein: I also think there’s something there about our narratives about intelligence and genius.

Hyman: Yeah.

Epstein: It seems to me the only way we’re able to justify all of this to ourselves is to subconsciously or consciously convince ourselves, through somersaults of cultural manipulation, that some people are just so brilliant, so ingenious, so special that they absolutely deserve to be at the center of this kind of dramatic transformation and disruption.

That it’s their brilliance that justifies all of this injustice because they thought it all up. If we didn’t perceive things that way, then the radical inequality we’ve been discussing would just come down on us in a landslide of moral reckoning. But that landslide never comes because we believe these things about intelligence. What do you think?

Hyman: Meritocracy is the legitimating ideology of our age. It has been for decades. A lot of tech innovators are very smart — nobody’s saying they’re not.

They’re creative people, but without that ability to build what they’re imagining through these millions of people, it wouldn’t have been possible. Also, there’s always somebody smarter.

I don’t know if I want to live in a society where just because I’m not as smart as you are, I don’t get to have a stable life. And I think fundamentally, that’s the moral question.

Epstein: I think that’s a moral question and I also think it’s important to recognize that it’s a lot easier to be smart when you have a stable life.

Hyman: Yeah.

Epstein: Or at least when somebody involved in raising you had a stable life, or at least when your entire society wasn’t disrupted again and again and again and again for 500 years or 1000 years. That makes it a lot easier to develop certain kinds of intelligence.

One of the things people are responding to right now in our current politics is that Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ayanna Pressley, Ilhan Omar, and people like them, I mean, to me they’re just obviously really brilliant. And people sometimes don’t know what to make of that because it defies the stereotypes they’ve internalized.

But anyway: if tech leaders in Silicon Valley today look at an issue like immigration and see themselves as not responsible for our current troubles, what would you say to that?

Hyman: I think what Silicon Valley wants are cheaper engineers, H-1B visas. They want to be able to push the psychic trauma of machine learning training outside the US to cheaper and cheaper pools of labor.

And I think they need to have a serious reckoning with themselves. about how I mean, machine learning offers a lot of opportunity. I’m not a Luddite. I’m not an anti-technology person, but I think we need to reconcile and be honest with ourselves about the trauma [involved in] these kinds of activities.

The hard question is, why are we so oblivious to it? Why do we not care about a woman in India who’s watching a day full of extreme videos, but we do care about a white man who might lose his arm in the factory?

And truthfully we didn’t always care about white men losing their arms in factories, getting back to the history. But it was the organization of those workers from the bottom up, [and] the passage of laws from the top down that made it possible to have factories that were both productive and also more humane.

I think that’s what we need today. How do we make our workplaces more humane around the world, as well as productivity.

And that is, again, the story of bottom-up and top-down. But the very first part is acknowledging the pain that is currently being caused by our industries.

Epstein: Given discussions today about a Green New Deal and green technology that would ostensibly be crucial to it, you write in Temp about the New Deal and how it created, for the first time, healthier working conditions for Americans, which various business interests then worked to disassemble for profit.

That asset stripping of decent government is what followed The New Deal, essentially. Do you see people hoping to rescale that mountain in an environmentally sustainable way?

Hyman: I would agree with that. The New Deal had its limits and its limits were about gender and race and nationality.

Very intentionally, the New Deal was about white American citizens who were men. The story I tell in Temp is the story of the people who were left out of that world, on whose backs our contemporary instability is rehearsed – women, people of color, the undocumented.

And it doesn’t have to be that way. I mean we could have a green New Deal that is more inclusive, [as] I wrote for The Atlantic a few months ago. That’s what’s so scary to Trump about the Squad, that they are saying “We insist on being treated as full humans, as full members of society.”

Epstein: As I ask at the end of all my TechCrunch interviews, how optimistic are you about our shared human future?

Hyman: Oh, wow. You know what? I’m a compulsive optimist and I think it’s important to be an optimist. It’s so easy to retreat into pessimism. To see the rise of White Nationalism and environmental decay and inequality and think that nothing can be done.

And the role of a historian is to denaturalize the changes in our society, whether that’s cultural or economic and to make sure that we reposition these changes as choices that we make. We make choices to turn industrial capitalism from a place where you could lose an arm and get poor into something that today we’re nostalgic for.

And to a place of prosperity. And that is exactly the same kind of operation of capitalism, but we just made it different. We made it work for us rather than work us over.

So [today,] how do we create a green capitalism that provides a good life for American workers, that provides a decent return for investors, just like we did in the post-war? That’s the great political question of our age; I think we can solve it.

I don’t know whether we will solve it. It’s very easy to fall into short-term thinking or into anti-humanist nationalist values and that does scare me.

Epstein: Okay. Louis Hyman’s book is Temp: How American Work, American Business and the American Dream Became Temporary. I hope everybody reading this interview will buy a copy, because it’s necessary stuff.