There are successful companies that grow fast and garner tons of press. Then there’s Roblox, a company which took at least a decade to hit its stride and has, relative to its current level of success, barely gotten any recognition or attention.

Why has Roblox’s story gone mostly untold? One reason is that it emerged from a whole generation of gaming portals and platforms. Some, like King.com, got lucky or pivoted their business. Others by and large failed.

Once companies like Facebook, Apple and Google got to the gaming scene, it just looked like a bad idea to try to build your own platform — and thus not worth talking about. Added to that, founder and CEO Dave Baszucki seems uninterested in press.

But overall, the problem has been that Roblox just seemed like an insignificant story for many, many years. The company had millions of users, sure. So did any number of popular games. In its early days, Roblox even looked like Minecraft, a game that was released long after Roblox went live, but that grew much, much faster.

Yet here we are today: Roblox now claims that half of all American children aged 9-12 are on its platform. It has jumped to 90 million monthly unique users and is poised to go international, potentially multiplying that number. And it’s unique. Essentially all other distribution services offering games through a portal have eventually fizzled, aside from some distant cousins like Steam.

This is the story of how Roblox not only survived, but built a thriving platform.

Seeds of an idea

(Photo by Steve Jennings/Getty Images for TechCrunch)

Before Roblox, there was Knowledge Revolution, a company that made teaching software. While designed to allow students to simulate physics experiments, perhaps predictably, they also treated it like a game.

“The fun seemed to be in building your own experiment,” says Baszucki. “When people were playing it and we went into schools and labs, they were all making car crashes and buildings fall down, making really funny stuff.” Provided with a sandbox, kids didn’t just make dry experiments about mass or velocity — they made games, or experiences they could show off to friends for a laugh.

Knowledge Revolution was founded in 1989, by Dave Baszucki and his brother Greg (who didn’t later co-found Roblox, but is now on its board). Nearly a decade later, it was acquired for $20 million by MSC Software, which made professional simulation tools. Dave continued there for another four years before leaving to become an angel investor.

Baszucki put money into Friendster, a company that pre-dated Facebook and MySpace in the social networking category. That investment seeded another piece of the idea for Roblox. Taken together, the legacy of Knowledge Revolution and Friendster were the two key components undergirding Roblox: a physics sandbox with strong creation tools, and a social graph.

Baszucki himself is a third piece of the puzzle. Part of an older set of entrepreneurs, which might be called the Steve Jobs generation, Baszucki’s archetype seems closer to Mr. Rogers than Jobs himself: unfailingly polite and enthusiastic, never claiming superior insight, and preferring to pass credit for his accomplishments on to others. In conversation, he shows interests both central and tangential to Roblox, like virtual environments, games, education, digital identity and the future of tech. Somewhere in this heady mix, the idea of Roblox came about.

The first release

Roblox, initially called Dynablox, was started in 2004 by Baszucki and Erik Cassel, an engineer who had worked at Knowledge Revolution.

It wasn’t alone. Roblox was founded during a fertile period for large virtual worlds and gaming platforms: broadband adoption, hardware improvements, the growth of multiplayer gaming and the recovering Silicon Valley ecosystem all played into producing immersive environments for socialization like Second Life (founded in 2003), IMVU (2004) and Metaplace (2006). In its pursuit of a younger audience, Roblox also shared DNA with children’s platforms like Habbo Hotel (2000) and Club Penguin (2005). It even bore some resemblance to casual game platforms like King.com (2003) and Kongregate (2006).

In the beginning, the two co-founders weren’t always sure what made their particular vision unique. “We had a couple false starts, but we finally said, we have to go for this complete unifying product,” says Baszucki.

The vision that took shape has lasted until the present. Roblox would rely on user-generated content — games made by the community. But it would take responsibility for everything else. The company would create the game development tools, and operate the servers that ran them. It would build the discovery portal, and add social features like chat and friends. To kickstart the community, it would even build its own games.

Any one of these activities would be enough to occupy a startup. For instance, the game engine Unity was founded in the same year as Roblox. Both are 3D game engines with similar functionality, allowing users to build environments and write scripts controlling every facet of gameplay. Roblox even has an advantage over Unity, in that it provides the multiplayer backend that can support up to 100 players in each shard of a game.

But Unity stopped with the engine. Roblox still had to build everything else. In practice, that meant tackling features one by one — making the most basic, stripped down version possible of each feature. During 2004 and 2005, Baszucki and Cassel worked alone to build out alpha and beta versions of the game.

The first live prototype of the Roblox environment, released during this time, was incredibly rough. “We had a big debate about whether it was ok to ship the avatar before it animated,” recalls Baszucki. The answer was yes. A few dozen testers, brought in through display ads, played a version of the game with stiff avatars that floated around like ghosts. They even complained when a later update added animations.

But the true test was whether community members would use the creation tools, which were rough and limited at first. Baszucki and Cassel launched the first edition of Roblox Studio in 2006, and community members immediately began making their own games, rivaling what Roblox itself was making. “It was way better than anything we could think of. We were getting paintball wars, model trains we could ride, Halloween mansions,” says Baszucki.

In the middle of the same year, Roblox hired its first employees, who immediately dove into building out its other features. Matt Dusek, one of the first two hires alongside John Shedletsky, built some of the early communication features. “Back in 2006, it may be a little difficult to put yourself in the mindset, but playing together online was still a chore. There was no social graph, so early on I built the friend system. They had a message board at that time, but there was no private messaging, so I built a private messaging system. We started laying a lot of the groundwork,” he says.

Shortly after hiring Dusek and Shedletsky, Roblox closed a series B investment for $1.1 million, securing its immediate future. During the following two years, the company continued developing features for the creators and community as well as games that lived on the portal. However, in 2008 it stopped routinely making games: the creator community had grown large and active enough to create most content. The foundations were in place — they simply needed years of hard work.

Sticking to a vision against all distractions

Roblox Developers Conference

Of course, simply saying a company needed years of work trivializes the nature of building companies.

For one thing, there were all the distractions. Companies from Roblox’s generation were constantly trying out different strategies, and ignoring the successful ones was not easy. Club Penguin, for instance, had bet on making its own environment, a sort of massively multiplayer online game for kids, and became so successful that it sold to Disney for $350 million in 2007. Second Life had lower user counts, but seemed to attract an endless amount of attention from the press.

In casual gaming, the tides were shifting. Apple’s App Store launched in 2008, and would become central to mobile gaming in the ensuing years. Facebook was even more attention-grabbing, with Farmville reaching 20 million MAU by October 2009. These two destinations for games pulled the attention of many of Roblox’s peers. King.com, for instance, joined the Facebook rush in 2010 and abandoned its portal in subsequent years. It even managed to look prescient, once Candy Crush Saga was released in 2012. Roblox launched its own iOS app the same year, but stuck with its strategy: players had to use its portal to enter individual games.

Also in 2009, Mojang released Minecraft with a similar blocky look but with a single world entirely produced by its developer — a game to Roblox’s platform. It reached 10 million paying users by 2013. “Minecraft was one of the biggest events. When Minecraft arrived, with a very similar audience, it just blew through Roblox. It took some fortitude to not just copy Minecraft and say that’s more of a game, we should be more of a game,” says Adam Miller, the VP of Engineering, Technology at Roblox.

In some ways, Roblox stayed trendy: for instance, it launched sales of its Robux currency in 2008 and virtual goods for developers in 2013, adding microtransactions at a time that much of the game industry was still trying to come to grips with the idea of free gaming. It also supported and nourished a community of unpaid content creators during a time that few other companies had done so, with a few exceptions like YouTube.

Still, the activity taking place in gaming was a philosophical threat. When a company in Roblox’s space hit it big, years before Roblox itself had any hope to, that winning strategy became a temptation. “There are friends, acquaintances, competitors chattering in your ear and saying, maybe you can just do that,” says Dusek.

But ultimately, competitors served to highlight what made Roblox’s vision different. “We were talking about Second Life and their wandering from virtual world to an adjacent virtual world. Is that really what we see? You walk from Pirate to Astronaut to Dinosaur land? You could do that, but it’s not what we saw,” says Dusek. Instead, the Roblox team stuck to its vision of a platform with many games.

Other distractions popped up as Roblox hit on internal features that became short-term successes, exclamation points in the daily grind of building a huge platform. One of these was hats. As any dedicated gamer knows, the shooter video game Team Fortress 2 is famous for its hats, which are sold and traded between players. It’s the basis for the game’s enormous economic success. Roblox had the same feature: its first effort at selling virtual goods was player hats, which players seemed to love. “The early introduction of hats was so overwhelmingly successful. There was this clear pent-up demand… so there was the idea that we could have a whole company about creating an online persona,” says Dusek.

The ability to ignore these distractions is a facet of Roblox’s success that should not be underestimated. Without exception, everyone TechCrunch spoke to for this article lays much of the credit for this stubborn adherence to a vision at the feet of Dave Baszucki (except for Baszucki himself, who gives the credit to the whole team).

“Next to Mark Zuckerberg I haven’t seen someone as mission-focused and vision and long term focused,” says David Sze, a managing partner at Greylock Partners who led Roblox’s most recent $150 million round. Sze knew Baszucki in those early days and watched Roblox as it grappled with these early questions. “He got tons of pressure that it wasn’t working and he needed to change things… [but] he really understood the pieces that needed to come into place and never wavered from that, whereas other people had pieces of the vision and didn’t stick with it for the long term.”

Sze, it should be noted, makes these observations in retrospect; he knew Baszucki because their kids went to the same school, but didn’t invest in Roblox’s early rounds. And indeed, it may be easiest to see Baszucki as a visionary in retrospect. He lacks the impatience and willfulness that, for better or worse, have come to be associated with the fiery-eyed prophets of tech. He simply seems quite sure of what he knows — and what he knows is Roblox’s long-term vision.

Building a community

(Photo by Leon Neal/Getty Images)

Recounting Roblox’s early years is easy: the company was still adding features and nailing down its strategy. But there were 15 long years between founding and the current day, an eternity for a consumer company. The years it took to build on the platform look, from the outside, like a long, slow buildup.

“The way I’ve looked at it is you have a broad swathe of different components, and Roblox started by building all of them in the most primitive fashion possible and iterating on them over time. I think it’s a little hard for people to see even internally how it changed over time because it’s so incremental,” says Adam Miller, the VP of tech.

The best place to see these changes might be the platform itself. Nearly every game ever developed on Roblox is still live, thanks to an effort to update tech over time without breaking old games.

Older games look blocky and primitive in both their environments and avatars. Over the years, that look has become more polished. Avatars in newer games became sleeker and more streamlined. The blocky terrain now includes smooth, complex shapes. The game UIs have improved, which has an impact on how the social features look and feel. Performance has also gotten better, and the game now runs well on both PC and its mobile app, which was released in 2012 and now accounts for more than half of all users. Less visible, but still important, it became harder to cheat due to a change in how the server and client communicate.

But those are the major changes. The actual day-to-day changes were typically much smaller. Matt Dusek describes a blade server sitting on a plastic chair in a back room, used to create thumbnails for games. “It was screen scraping pixels, but what that meant was whenever you had a Windows update, the update would pop in front of it and all the thumbnails would show a corner of the Windows update box on it.” Replacing early band-aids like that server was a process that took years.

Adam Miller, the VP of engineering, relates another story about arriving at the company eight years into its existence and realizing that the game seemed to run at only 30 frames per second. “They were like, no no, it’s 60. So we looked at the screen and measured it, and sure enough, we were rendering at 60fps but we were running the world step once then rendering two frames.” Needless to say, that particular issue was quickly fixed, but plenty of low-hanging fruit remained.

It was also in those middle years when community developers became more important. In the early years, Roblox made its own games, many of which were popular. Later, the company stopped making games of its own: it was up to the community to create everything.

But most Roblox developers were just kids. Matthew Dean started developing games on Roblox when he was 16. After a few tries he hit on a success, called Catalogue Heaven. But he was so casual about the entire experience that he didn’t even track the game’s number of players. “I built out the game in a couple weeks, published it, told people about it, it didn’t get any traction, so I forgot about it. Six months later I looked at the front page of Roblox and it was at the top, out of the blue. I don’t know how it got there,” recounts Dean, who is now a product manager at Roblox.

If there’s any way to summarize those long years of gradual growth and improvement, it’s by Roblox’s continued adherence to the long-term plan. “Five years ago, Dave led this initiative to create a document that was a shared reference point for the company about the vision we agree on,” says Miller. “We’d get into a room and debate them, and once we got to an agreement point it became a document we could refer to, and once a year I’d give a talk to the org. We brought it up just recently, and every item on there was still valid.”

Losing a co-founder

One event does deserve a special highlight. In 2013, Baszucki’s co-founder Erik Cassel passed away. “He almost had like an upset stomach one day and went home, and we found out he had cancer,” says Baszucki.

Cassel was the kind of technical founder that startups hope and wish for: he was capable of building systems that lasted, even in their earliest form. “Erik was a master of prototyping, but with the qualification that his prototypes could run in production for several years. He would bang it out and a team would produce it in coming years,” says Dusek.

“For many of the key foundational elements of Roblox, he’d come up with the super-long view,” says Baszucki. “There was an early example wherein my more primitive way I was trying to figure out architecture around scoring and games, and Erik said we have to embed Lua scripting so you can do anything, rather than burn stuff in. Having an elegant, simple view was really powerful.”

Cassel’s colleagues remember him as a kind and gentle presence, who taught the earliest engineers at the company their trade.

“The really wild thing was, when we read all these books about people who get cancer, I have this preconceived notion that I drop everything, climb Everest and hang out with family. With him, this was exactly what he wanted to do. He kept working right up to the end almost,” says Baszucki.

The modern era

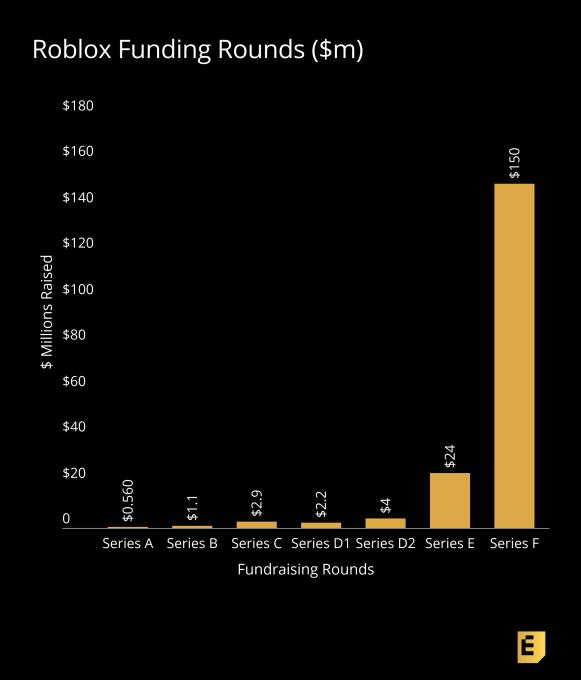

With such a long buildup, it’s not clear when Roblox could finally be qualified as a success. Maybe it was in December 2016, when the platform announced that it had reached 30 million monthly active users. Or in March 2017 when it announced a $24 million Series E. The company raised another $150 million in September 2018, and trebled its MAU count by April 2019, reaching 90 million monthly users.

Or it may still not be the right time to declare Roblox a success. If there’s anything to learn from the company’s long life to date, it’s that it would not have survived with goals like an ordinary consumer startup. There was no viral inflection point, no quick turnaround for early investors. Roblox has stayed focused on long-term, almost philosophical goals: building a new category of entertainment and communication, not just a company or quick cash-out.

“We’ve had this attitude that the product is never finished. We think of it in terms of percent to the vision. When we launched on it was 3 percent. We still carry that forward today,” says Baszucki. Later, he mentions having a 30-year vision in which users have a fully-fledged digital identity — perhaps in an immersive environment like Roblox.

The work coming out of Roblox’s engineering teams also indicate that the company still sees itself as building foundations. For instance, the company spent several years and a significant amount of its engineering resources designing its game engine so that it can also run its app infrastructure, and writes to the lowest level APIs available on each platform, such as Metal on iOS. As a result, Roblox now runs with native-level performance on devices like the iPhone, Android, and the Xbox, but only needs a handful of engineers to maintain those apps. “Doing this has been a three-year-long effort at Roblox, and I don’t know many companies at our size, at the time 100 now almost 500, willing to expend that much engineering effort for that long a payoff,” says Claus Moberg, the senior director of engineering who led the effort.

Whether Roblox can be called a success or not, incoming funding and players pouring in have kicked the company’s recruiting into high gear. Grace Francisco, for instance, who was Atlassian’s head of developer relations, moved to Roblox as a vice president for their growing developer community. Enrico D’Angelo, an executive at Activision, came in as Roblox’s vice president of product. Dan Williams left Dropbox, where he was a director of infrastructure engineering, to lead Roblox’s shift onto its own cloud, building its own server farms and moving off managed services like Amazon AWS. Chris Misner, a former Apple general manager of Asia-Pacific, came on as president of international.

Much of the new blood in Roblox represents either new initiatives, or vast expansions of old priorities. Developer relations, for example, has been important at Roblox since Studio was launched in 2006. But as the developer community grew — currently, it’s at 2 million creators — the company has added in more ways to interact with that community. It allows some of the most successful creators to work out of its San Mateo office. The company started an accelerator for developers and teams in 2015, and a conference the same year.

In short, Roblox has left behind its slow, steady growth and moved into a period of high growth. It’s not a risk-free transition. The company still has to win the international audience, as well as older players. It must survive newer competitors and changes to the social network landscape.

Continue to part 2 of our Roblox EC-1 to learn how the company is navigating these challenges.

Roblox EC-1 Table of Contents

- Part 1: Origin story

- Part 2: Growth strategy

- Postscript: Lessons learned

Also check out other EC-1s on Extra Crunch.

Update: The graph of Roblox’s funding rounds was corrected. The company’s series E round was $24 million, not $92 million as originally depicted.