Cities use paint and signs to communicate the rules of the road in a world where urban spaces must choreograph an infinite dance between pedestrians and personally owned cars, scooters and bicycles, ride-hailing services, delivery trucks, buses, rail and, someday, autonomous vehicles.

It’s a crude method for increasingly modern cities that are trying to juggle all the ways people and packages get around. It also has limitations. Paint fades. Signs become obstructed. And companies deploying dockless scooters or autonomous vehicles have no easy way to access the rules of the road.

And that’s where Inrix, a global transportation analytics company, sees an opportunity. The company is taking a digital data platform that it developed for autonomous vehicles and expanding it to all forms of transportation.

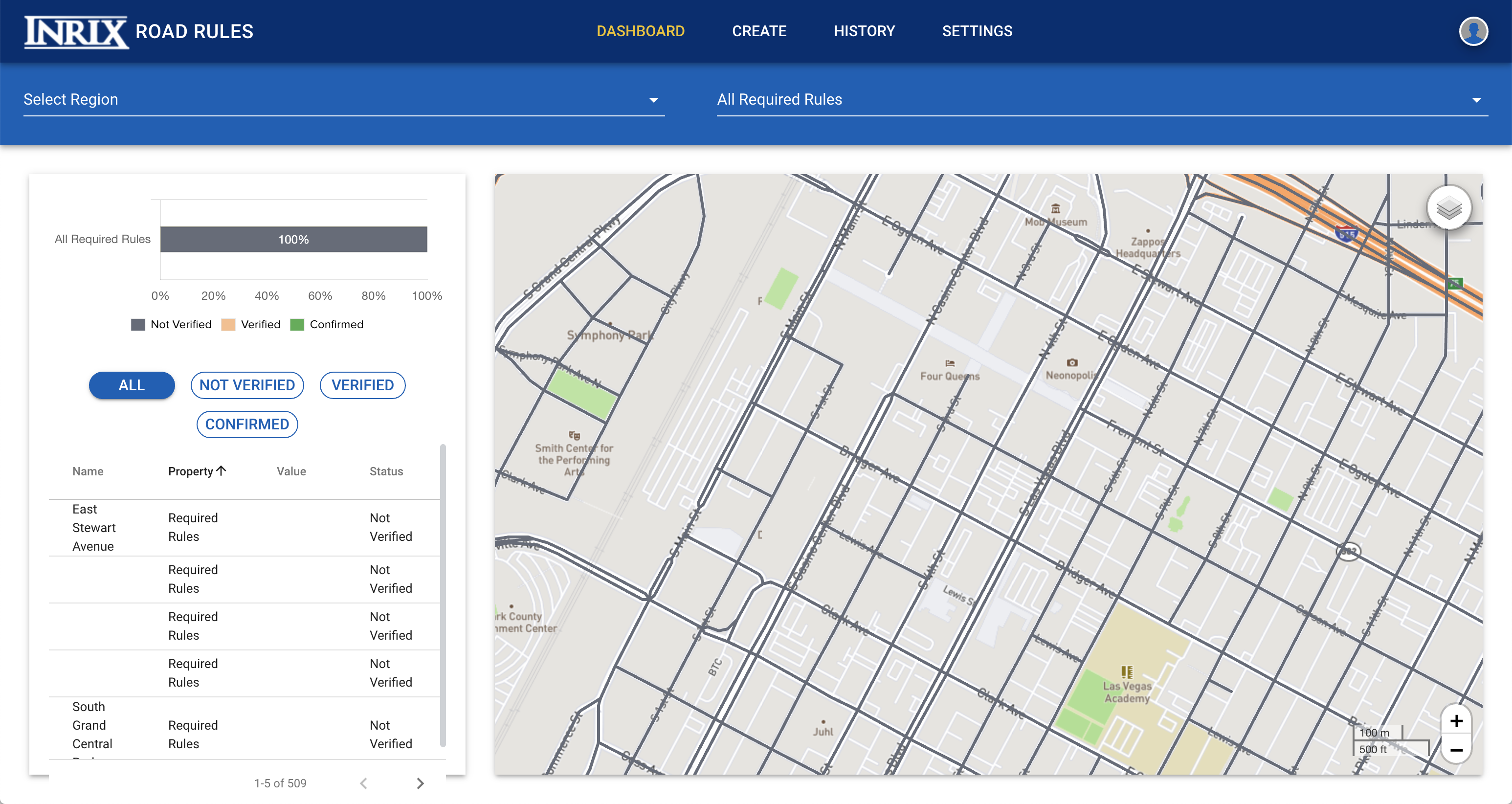

The platform, called Road Rules, was designed to help cities create a digital record of their traffic rules and restrictions. Inrix said that 11 cities, including Austin, Texas, Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts, Calgary in Canada, Detroit, Miami-Dade County, and the Regional Transportation Commission of Southern Nevada, which includes Las Vegas, have signed on to implement Road Rules and are digitizing their infrastructure and restrictions this year. Four companies — Jaguar Land Rover, May Mobility, nuTonomy (an Aptiv company) and operators running Renovo’s Aware platform — have also agreed to use the data authored by the cities.

All of the cities that have signed on are thinking about or already have autonomous vehicle companies testing or running pilot programs on public roads. The expanded version of the platform is designed to help these cities manage and communicate rules to companies deploying other forms of mobility, whether it’s a delivery bot or dockless scooter.

The tool is set up to make it easy for a city employee to enter roadway information, such as traffic signals and pedestrian crossing signs, as well as rules for curbs and sidewalks, including where loading zones, EV charging stations, dockless bike and scooter operational domains and shared-vehicle drop zones are located.

The platform initially launched as a pilot program in July 2018. This revamped and expanded version, which goes public Wednesday ahead of the TC Sessions: Mobility event in San Jose, has a new user experience, and clearer work-flows are supposed to make it easier for road authorities to digitize and manage transportation rules. And, of course, there’s the expanded focus of the platform, which should make it far more useful for cities grappling with today’s mobility problems, not just the ones a decade from now. But the killer feature is the ability for cities to share that data across departments, with other agencies and even companies.

“Cities were looking for a platform that is actually open,” Avery Ash, head of Inrix’s autonomous mobility division, told TechCrunch recently. “This keeps the control in the hands of the city to be able to manage, update and distribute the data that they are validating — and then it can be easily shareable.”

This shareable open component part is based on the National Association of City Transportation Official’s SharedStreets project, which has created a global referencing system. This means that the city, agency or company that is getting information out of Road Rules can easily snap it to whatever map they’re using.

Inrix has grand ambitions for Road Rules. Ash told TechCrunch the company is aiming to get 100 cities on the platform by the end of 2019. And here’s why cities might bite. There are companies that can provide cities with data. Inrix’s platform lets cities build this database on their own, control it and share it.

Building a database of road rules is still a massive undertaking by any city. Some of that process can be automated, although the information coming in would likely require validation from a city employee.

Ash also said that cities will likely target small sections of a city at first and slowly expand from there. For instance, a specific block where dockless scooters might be allowed to operate under a temporary permit, or a loop where autonomous vehicles might be tested and eventually deployed.