Deciding what to patent can be a confusing process but by creating a formal process it is something that every startup can manage.

Intellectual property (IP) is one of the most valuable assets of a startup and patents are often chief among IP in terms of value. Patents allow the startup to prevent competitors from using their technology, which is a powerful feature that can grant unique advantages in the marketplace.

From a business perspective, patents can help with driving investment and acquisitions, provide protection during partnerships and business deals, and help defend itself against patent lawsuits by others.

However, startups also often have a hard time determining when and what to patent. Innovative startups are inventing new things on a regular basis, and there is a danger of slipping into a haphazard approach of patenting whatever happens to be available rather than systematically analyzing the business needs of the company and protecting the IP that moves the needle the most.

Moreover, startups must balance the need to protect IP with other areas of the business: Patents are complex documents that require an investment of time and resources to obtain. They often require specialized legal counsel to write and a lengthy examination process at the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (USPTO).

This article is a how-to guide for startups to make the decision on when and what to patent with a mature approach to IP strategy.

Table of Contents

- Creating a regular IP harvesting process

- Invention cataloging and scoring

- The scoring system

- Conclusion

Creating a regular IP harvesting process

In order to make a decision about what to patent, a startup must first know what IP it has. For very small teams, it may be possible for everyone to have a shared idea of the IP. However, once teams grow beyond a few people, it is no longer possible to have complete visibility into what everyone on the team is doing and potentially inventing. Therefore, a regular IP harvesting process must be put in place to ensure proper reporting of IP to the executive level.

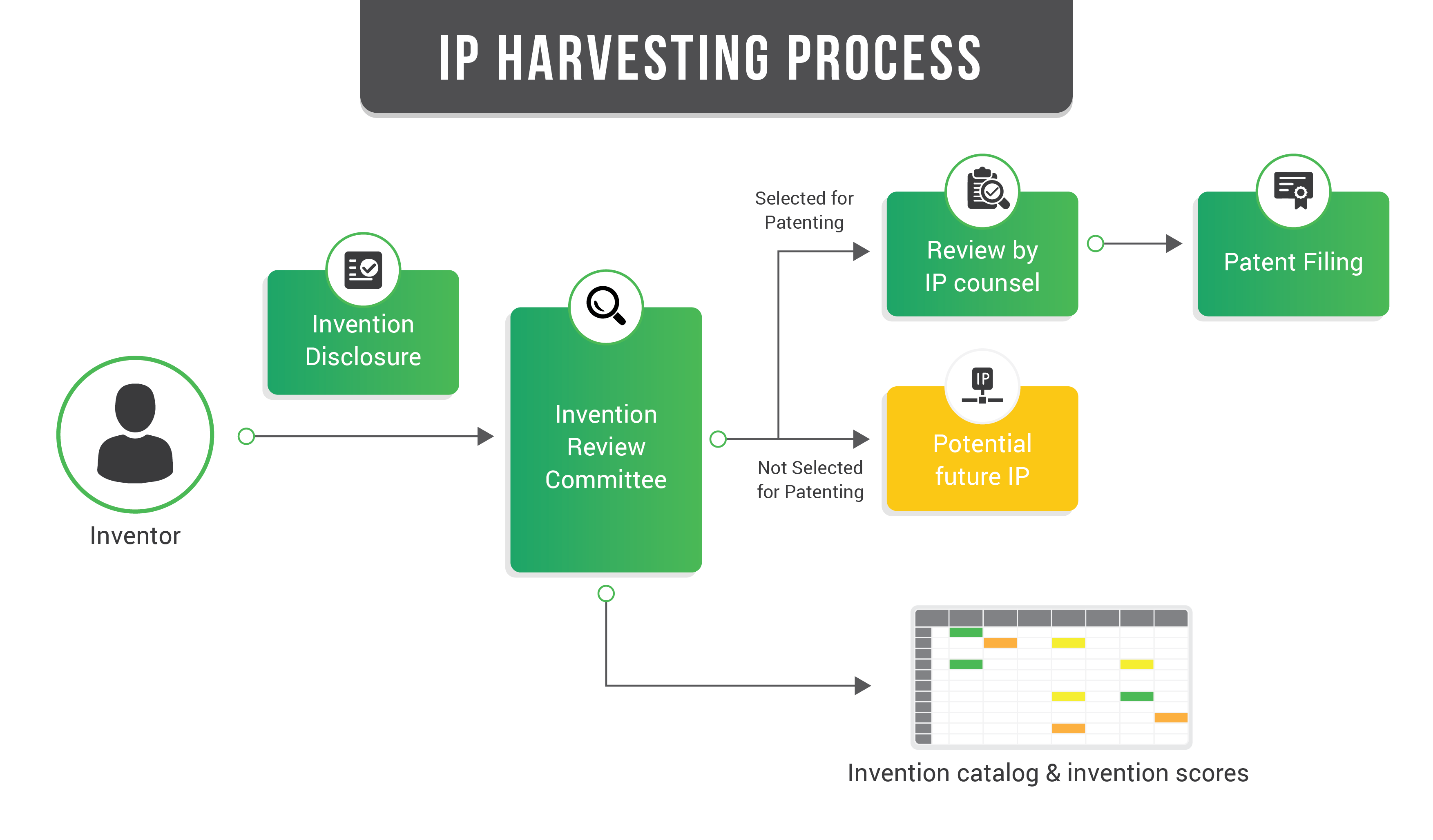

Most startups are best served with a simple IP harvesting process involving just three steps: (1) disclosure (2) invention review and (3) patent filing. In the disclosure stage, employees who are in IP creation roles must be trained to disclose ideas that are potentially protectable IP.

At this stage, as the name suggests, the startup wants employees to disclose as much as possible so only a coarse filter should be used. The ideas will be further filtered later. Employees should be trained to disclose inventions so long as they meet two criteria: first, that the invention gives the company a competitive advantage and, second, that the invention is new.

Both criteria should be low bars and employees should disclose inventions so long as both criteria are at least minimally met. When an employee identifies an invention meeting the criteria, he or she should complete an invention disclosure form to describe the invention – a process that should only take 15 – 30 minutes.

In the invention review stage, members of an invention review committee review the invention disclosures and enter them into an invention catalog along with scores along different factors, as discussed further below. The invention review committee should be selected from the team members who are most interested and excited about IP.

The invention review committee selects the most promising inventions and discusses them with their IP counsel. IP counsel can help the invention review committee determine the appropriate goals, such as how many patents to pursue, which products to protect, and the timeline, and determine which inventions to file as patents to meet those goals.

This leads to the final stage, patent filing, where the IP counsel handles the task of drafting and filing the patent applications with the assistance of the inventors.

Invention cataloging and scoring

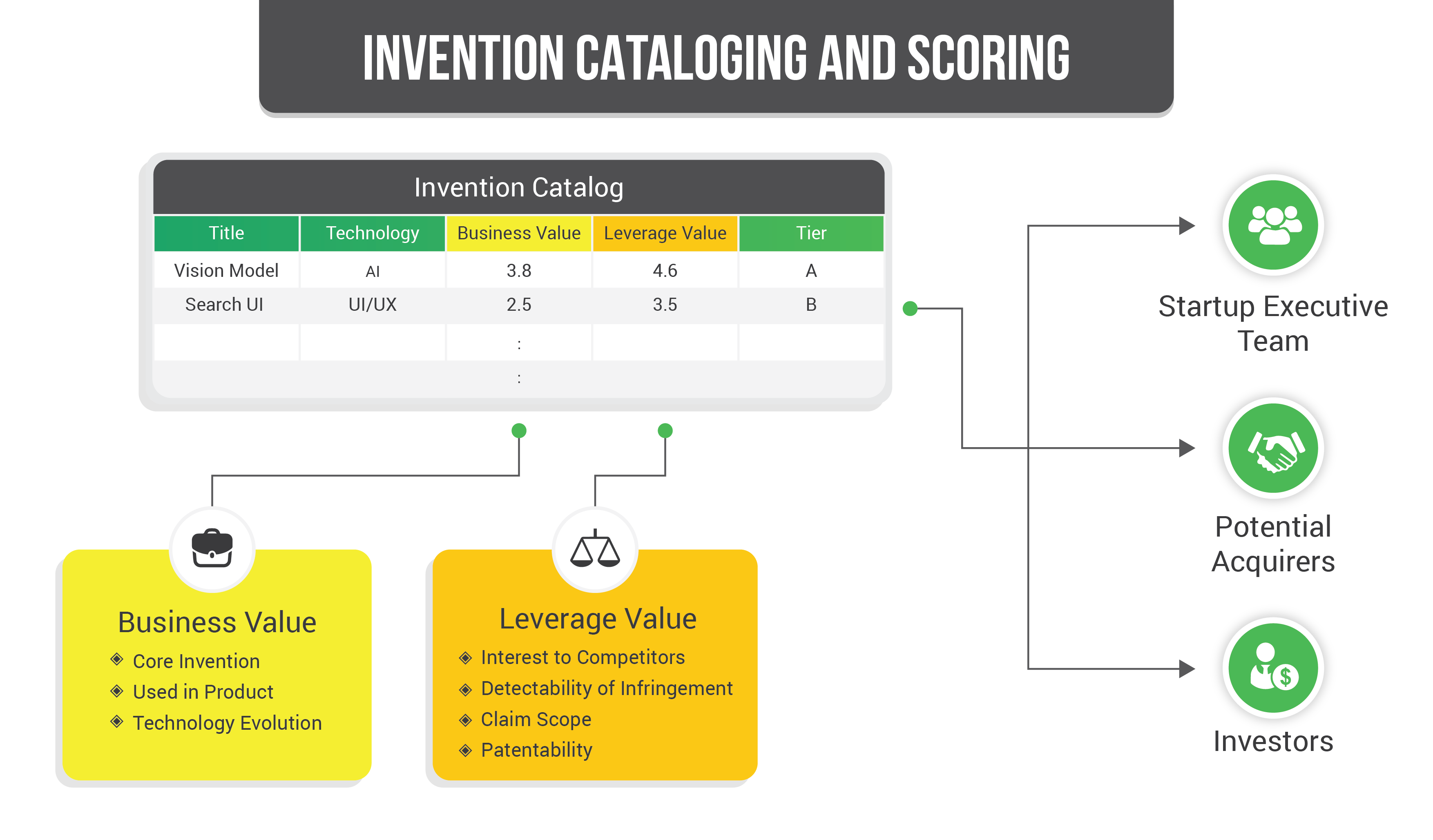

Developing an invention catalog is critical for startups to know what IP they have, and, by the same token, an invention scoring system is essential for startups to be able to sort through the catalog of IP and determine which ones to prioritize for IP protection. Invention scoring systems are used very commonly at large companies, and the best practices from that realm are applicable to startups too.

The invention catalog serves as the centralized documentation about the IP of the startup. It isn’t just the inventions that are chosen for patenting that are valuable. Even inventions that are not pursued as a patent can still qualify as IP in the form of trade secrets. The catalog is useful documentation for proving the existence of trade secrets in later litigation or in an acquisition.

The invention catalog is a tool that can be used for anyone who wants to understand the inventive activity at the startup. Company leadership can use it to view snapshots of IP creation at the company. Another primary constituency is investors.

The invention catalog can be shared with investors during the fundraising process, sometimes with just the names of the inventions and without the details in order to avoid making a public disclosure that could eliminate trade secret protection or trigger a bar against obtaining patent protection in the United States or overseas.

This allows investors to measure the IP progress of the startup and the progression in the technology. Moreover, the catalog helps demonstrate to investors that the company understands the importance of IP protection.

Similarly, the invention catalog is also valuable when a startup is in talks with a potential acquirer. The inventions that have already been patented or are patent pending represent valuable IP but so can the inventions that have not been patented because they may have the potential for future patenting by the acquirer. In addition, the potential acquirer will want to know about the existing trade secrets, which are also included in the catalog.

An invention scoring system builds on the invention catalog by allowing startups to formally value the IP. The invention scoring system formalizes what it is that the startup is seeking in patentable inventions, which provides a number of benefits.

First, it allows training team members to know what to look for in a patentable invention. Without a system, team members will approach the problem of deciding what to patent with different values and goals and it is difficult to form a consensus.

Time ends of being spent in each discussion about what the evaluation criteria should be. Instead, the scoring system should be established ahead of time and individual discussion can focus just on the application of the scoring system to the particular invention.

The formality and objectivity of a scoring system also keeps startups’ IP programs on a consistent path. It helps protect against variance that can arise from biases of the team members who are running the IP program and against any oversights. It also allows tracking progress on IP with metrics, so that it can be measured just like other business units.

In addition, the scoring system helps prioritize which inventions to patent next. With limited resources, startups need to pick and choose where to patent. The scoring system allows the startup to identify the most important IP to protect and the IP of lesser importance that can be deferred until later.

The scoring system

Image via Getty Images / nadia_bormotova

This section describes an invention scoring system that is appropriate for most startups. A spreadsheet for computing the scores is attached here. The system can also be customized to a startup’s needs by modifying the factors and increasing the weight of certain factors that are more important for the startup and decreasing the weight of factors that are less important.

An invention should be considered for patenting based on a total of two components: Business Value and Leverage Value. The combined Business Value and Leverage Value can be ranked on a 3-tier scale of A, B, and C.

The top tier A, B ideas are those that the company should pursue for patenting. In addition to the tier, it is also useful to track the technology area that the invention relates to so the company can ensure it has diverse coverage across its most strategically important technology areas.

Business Value and Leverage Value are each weighted scores of multiple factors rated on a scale of 1-5. Each factor is multiplied by one of a series of weights that add up to 1 and then summed to generate a score of 1-5 for the overall component. The Business Value and Leverage Value scores are combined together to form a total Composite Score. The Composite Score may then be ranked into a tier of A, B or C.

Business Value measures factors related to importance to the business and is also referred to as internal value because it is inward-looking to the business. The factors are: core invention, used in product, and technology evolution.

Core Invention measures how core the invention is to the startup’s business. Inventions that are core to the business are those that are central to the success of the overall business. High scoring inventions are those that are the secret sauce or main competitive advantage of the business. Inventions that are more peripheral should be given lower scores.

Used in Product is a measure of whether the invention is used in the startup’s product and how important it is to the product. If the invention is the main driver of marketing and sales of the product, then it would receive a high score. If the invention is not used in the product at all, or used in only a peripheral feature than it should receive a lower score.

Technology Evolution measures how big the evolutionary jump is when the invention is compared to prior versions of the technology. Bigger leaps in technology deserve higher scores, while more incremental improvements receive lower scores.

Leverage Value measures factors related to importance to competitors and the market and is also referred to as external value because it looks externally to the business. The factors are: interest to competitors, detectability of infringement, claim scope, and patentability.

Interest to Competitors measures how interested competitors will be in the technology. Technology that is highly sought by others in the market will be more valuable than if no one else wants to use it.

When competitors will be very interested in the invention, then a higher score is merited. If competitors will not be interested in the invention, then a lower score should be given.

Detectability of Infringement is a measure of how easy it is to detect if others are using your invention. The importance of this measure is two-fold. First, when an invention is easier to detect, it is easier to pursue the competitor for licensing fees or in litigation because the case for showing patent infringement is more apparent.

When the invention is hard to detect, it can be hard to know if competitors are using the technology, which hinders licensing, and also makes it more difficult to bring a patent infringement lawsuit (because the startup must be aware of reasonable grounds for believing someone is infringing the patent to file suit).

Second, inventions that are easier to detect are also easier and more likely for competitors to copy. When a feature is visible, like a user interface element, it is ripe for competitors to adopt into their own product.

Image via Getty Images / Giii

Claim Scope is a measure of the breadth of a patent’s claims. The claims determine the coverage of the patent and are written in legal language to describe what was invented and what the monopoly covers. Patents have three main parts, the claims, specification, and drawings.

The specification and drawings can be thought of as the supporting part of the document that further explains the claims and shows that the startup is entitled to ownership of the claims. Broad claims mean that the claim covers a wide range of technologies, while narrow claims cover a more specific set of technologies.

It is more valuable for startups to obtain broad claims, so long as the broad claims are not so broad as to be invalid. Therefore, broader claims should be given a higher score and narrower claims should be given a lower score. Startups may benefit from having their IP counsel be involved in the process of rating claim scope.

Patentability measures how likely the invention is to be patentable. Patentability involves analysis of three different requirements: (1) the invention must be patentable subject matter (2) it must be novel and non-obvious and (3) it must be enabled and described by the patent.

The first criteria knocks out certain inventions that are considered to be abstract ideas, which mainly affects very abstract inventions such as mathematical concepts, certain methods of organizing human activity, mental processes, laws of nature, and natural phenomena. The second criteria relates to what is known as the prior art, which are inventions and ideas that already exist and have been publicly disclosed.

Critically, the invention must be new and non-obvious as compared to what already exists in the prior art. The more different or ground-breaking the invention is, the more likely it will be to meet this criteria. A rating based on the prior art may be partly conjecture since the startup is probably not aware of all the prior art that exists, and there are some potential disadvantages to performing a search for prior art, including the requirement to submit any relevant prior art to the USPTO during the examination process and the potential for increased damages due to alleged willful infringement if the startup finds an existing patent that it itself is infringing.

The third criteria, related to what are known as the enablement and written description requirements of patent law, comes into play with life sciences and hard tech inventions. In a patent application, the applicant must describe the invention in sufficient detail that a person having ordinary skill in the art would be able to make and use the invention.

For the life sciences and hard tech fields this can frequently include a requirement for experimental data to show that the invention actually works based on the details provided. Startups may also want to have their IP counsel involved in evaluating this factor.

After assigning a value to each of the factors, values for the Business Value and Leverage Value are computed based on the weights that were assigned to each factor. Inventions can be divided into A, B, and C tiers based on the Composite Score of the Business Value and Leverage Value, with the highest scoring inventions being in the A and B categories and being prioritized for patenting.

The catalog of inventions and scores should be treated as a dynamic document and updated at critical junctures. For example, as the company’s roadmap evolves, the invention may become more or less core to the company’s business or may or may not be included in future products.

In addition, other competitors may start to move toward or away from the technology. Also, during the patent examination process, it is common for claims to be amended, which affects claim scope. If claims are narrowed, then the value may be decreased.

In other cases, the claims may be amended to cover competitor products more closely, which should increase their value. By re-evaluating the Business Value and Leverage Value factors at these critical junctures, the Composite Score and tier of the invention may change. The company may then reassess the importance of the invention and whether to invest additional monetary resources in pursuit of patent protection for the invention.

Conclusion

IP is an important part of a startup’s value and a holistic approach should be taken to determining how best to pursue IP that will be valuable to the business.

It is important to look across the entire business for IP and not fall into the trap of deciding piecemeal whether to file patents based on a narrow view of one invention and without a broader view of the business. Implementing a process to harvest inventions, catalog them, and score them helps formalize the IP creation process at a startup and can help with decision making, fundraising, and potential exits.