As autonomous cars and robots loom over the landscapes of cities and jobs alike, the technologies that empower them are forming sub-industries of their own. One of those is lidar, which has become an indispensable tool to autonomy, spawning dozens of companies and attracting hundreds of millions in venture funding.

But like all industries built on top of fast-moving technologies, lidar and the sensing business is by definition built somewhat upon a foundation of shifting sands. New research appears weekly advancing the art, and no less frequently are new partnerships minted, as car manufacturers like Audi and BMW scramble to keep ahead of their peers in the emerging autonomy economy.

To compete in the lidar industry means not just to create and follow through on difficult research and engineering, but to be prepared to react with agility as the market shifts in response to trends, regulations, and disasters.

I talked with several CEOs and investors in the lidar space to find out how the industry is changing, how they plan to compete, and what the next few years have in store.

Their opinions and predictions sometimes synced up and at other times diverged completely. For some, the future lies manifestly in partnerships they have already established and hope to nurture, while others feel that it’s too early for automakers to commit, and they’re stringing startups along one non-exclusive contract at a time.

All agreed that the technology itself is obviously important, but not so important that investors will wait forever for engineers to get it out of the lab.

And while some felt a sensor company has no business building a full-stack autonomy solution, others suggested that’s the only way to attract customers navigating a strange new market.

It’s a flourishing market but one, they all agreed, that will experience a major consolidation in the next year. In short, it’s a wild west of ideas, plentiful money, and a bright future — for some.

The evolution of lidar

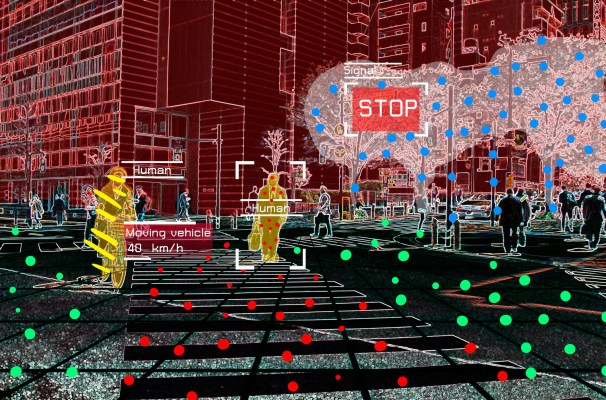

I’ve previously written an introduction to lidar, but in short, lidar units project lasers out into the world and measure how they are reflected, producing a 3D picture of the environment around them.

Lidar is being rapidly developed. So while the underlying principles may be the same from a decade ago, other aspects have changed considerably today.

The most visible change is the form factor. Not long ago the only really credible form of lidar was what is now called a spinner, which put the lasers and receivers in a little package like an ambulance’s spinning light unit. It’s a natural fit for the task of spraying lasers in a wide arc, and spinners have the advantage of 360-degree coverage. For this reason, Velodyne and its devices came to dominate the early days of autonomy.

Spinners, though, are also bulky and expensive, and their quickly-moving mechanical parts are prone to failure. That’s why a new wave of lidar systems emerged over the last couple of years that eschews moving parts and diversifies the technique in other ways.

The last two years have been salad days for startups in the space, as blue-sky research and production-ready engineering alike pulled in record funding as venture capital firms made early-stage bets and automotive concerns backed favorites.

Replacing the spinner with better concealed sensors

As the lidar industry has evolved, the consensus is that it’s slouching towards maturity, mainly by departing from the approaches that established it in the first place.

As the lidar industry has evolved, the consensus is that it’s slouching towards maturity, mainly by departing from the approaches that established it in the first place.

“The whole industry has matured in terms of understanding and technology,” explained Scott Burroughs, CEO of Sense Photonics. “We’ve seen some segmentation as well — it’s not just one-size-fits-all. I wouldn’t be surprised if over the next 12 months we see more segments appear as the OEMs, auto companies, and lidar companies all start to better understand what their needs are.”

Sense Photonics is a newer entrant that claims a major advantage due to its form factor, which allows the laser emitter and detector to be physically separated — making them much easier to conceal on an otherwise ordinary vehicle. The company recently announced a $26 million series A round.

Spinners are fine for pilots, but they’re not a good long term solution. They’re too big, expensive, and unreliable.

That is already a significant departure from how things were a few years back when Velodyne was the de facto standard and most early autonomous vehicles had the telltale bumps and buckets on top.

Another possibility for flattening the unsightly bump is to use what are called metamaterials: custom-engineered surfaces with useful properties, such as being able to steer a laser across the environment without complex mechanics or optics. Intellectual Ventures has a pretty strong grip on this IP, and it gave birth to metamaterials startups Echodyne (for radar) and more recently for lidar, Lumotive. The company has the (no doubt marketable) distinction of counting Bill Gates among its seed investors.

“The approaches that tests have relied on to date used what we call spinners. They’re bulky and costly; the advantage is you get 360 degrees, but if you put them on the roof you have blind spots all over the apron of the car, which is where all the action is,” said Lumotive CEO Bill Colleran. “So we hear people saying spinners are fine for pilots, but they’re not a good long-term solution. They’re too big, expensive, and unreliable.”

Burroughs thinks along the same line. “They’re really starting to think about integration right now, the tier ones and OEMs in particular,” he said. “No one wants a box on the top of the vehicle. Everyone wants to hide the sensors. That’s why we’ve found there’s a lot of interest in our solution: the ability to separate the laser emitter from the receiver makes it much easier to integrate it into the automobile.”

Moving from the lab into production

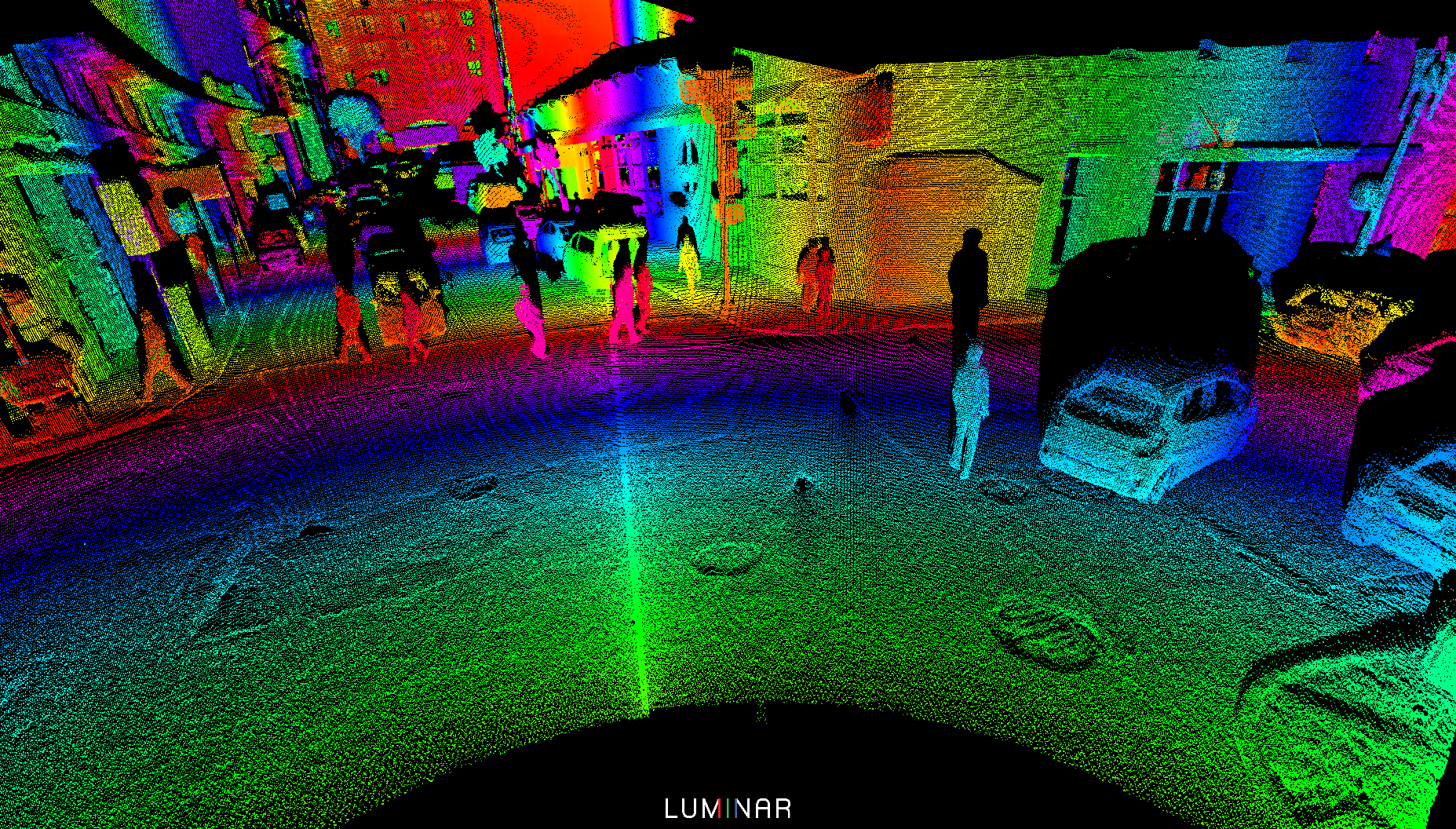

Visualization of data gathered by Luminar’s LiDAR, as a high-resolution point cloud. Courtesy of Luminar.

There’s no shortage of lidar alternatives — as long as you don’t need something that’s ready to roll off the production line.

“Almost everything is in R&D, of which 95 percent is in the earlier stages of research, rather than actual development,” explained Austin Russell, founder and CEO of Luminar. “The development stage is a huge undertaking — to actually move it towards real-world adoption and into true series production vehicles. Whoever is able to enable true autonomy in production vehicles first is going to be the game changer for the industry. But that hasn’t happened yet.”

Luminar is another relatively new entrant, pioneering a unique sweeping curtain method of scanning the scene. In a bid to achieve scale, it has also massively reduced the amount of exotic material (indium gallium arsenide) required to build its unit. But it is perhaps more well known (though he must certainly tire of hearing about it) for the youth and ingenuity of Russell, who was only 22 when the company came out of stealth in 2017.

Meanwhile, Israel-based Innoviz is hardly older than its peers, but has managed to out-raise them. With strong but comparatively straightforward tech and go-to-market, it has raised nearly a quarter of a billion dollars since 2017. Taking advantage of its less US-centric roots, it has established influential and far-reaching partnerships internationally and also seems the most practical of those I spoke with — not to say a wet blanket.

“Without touching on specific companies or issues, it’s not only about range and resolution and field of view and frame rate. It’s also very much about size and power,” said Innoviz CEO Omer Keilaf. “For lidar, because of the optics, there are only a few places where it’s really relevant — behind the windshield or grill, and those areas are very tight. Power consumption becomes an issue.”

The automotive companies are realizing that you only need to reinvent the wheel so many times.

“Those are discussions that are usually not public, but can be showstoppers,” he continued. “It’s really interesting to look how decisions are made in this industry. Car makers really need to have a risk-averse approach when they are going to production.”

Russell echoed his sentiment: “The automotive companies are realizing that you only need to reinvent the wheel so many times. At the end of the day, it’s absolutely critical for these automakers to be able to work with something that can be designed into their vehicle platforms.”

In other words, the likes of Audi and Toyota aren’t necessarily just picking the “best” tech, but rather the tech that’s best able to be married to existing design and engineering work.

Is it what you’ve got or who you know? (It’s both)

The risk-averse approach is very different from VC firms, which (supposedly) offset risk with careful research, often backing technological plays. Bridging the gap from high-risk VC seed funding to risk-averse major company funding is something few companies have been able to do.

“Early investments really get in the weeds technically. It’s a really big challenge for later stage investors to suss out the technical difference between the companies — they’re waiting for the market to speak, and when that happens they’ll jump in a big way,” predicted Congruent Ventures founding partner Josh Posamentier. Congruent is a newly launched $94 million fund focused on frontier tech, and an investor in Sense Photonics.

“There’s a lot of capital waiting on the sidelines,” he assured me.

Luminar’s Russell was more skeptical. “There’s definitely a number of VCs taking very early stage bets not understanding any aspects of the technology but hoping that something will work out,” he said (though, in the interest of preserving the peace, not in reference to Posamentier). But $5 million here and $20 million there, he pointed out, is peanuts compared with the billions being sunk into autonomous programs at large.

This results in tension between surpassing competitors with technological advances or establishing partnerships that pull a company above the pack.

Investors have started to realize that it’s about time to see proof, and not just proof of concept.

Innoviz made just such a partnership with BMW recently, and Keilaf said this was “tremendous” for the company’s recent $170 million series C round. Anticipating this would be their last raise, they targeted “deep pockets,” but those pockets would remain buttoned up tight if not for the BMW connection. “Investors have started to realize that it’s about time to see proof, and not just proof of concept. They want to see programs for serious production.”

Lumotive’s Colleran pointed out that without a partnership, you’re unlikely at this point to get the venture funding.

“Many existing players have already raised additional capital. What that means for new entrants is you need a specific technical advantage to your approach,” he said. Hence his confidence in Lumotive’s high-tech strategy.

There are lots of partnerships, and a lot of fanfare, but none to my knowledge are exclusive. It’s still the wild west.

Crucially, he and others pointed out, there are few if any strong commitments on either side of the table. “There are lots of partnerships, and a lot of fanfare, but none to my knowledge are exclusive,” he said. “It’s still the wild west.”

“Even if one company locks up an early OEM, that in no way locks them in long term, assuming you can drop into that socket, so to speak,” echoed Posamentier.

And a related advantage for the tech-loving startups is that automakers are hunting high and low for advantages during this comparatively early stage — as long as integration isn’t a problem, of course — and it’s unlikely they’ll overlook a truly good solution.

“They’re really good at boiling the oceans,” said Posamentier. “They have staff for that.”

Was 2018 ‘peak lidar’?

But while automakers keep an unblinking eye on the crowded lidar startup field, small fry are finding it hard to keep the lights on, let alone take over the market.

“I’ve been approached at least four times in the last two months with an offer to buy a lidar company,” said Innoviz’s Keilaf. “It doesn’t surprise me to see some convergence. While there are 20 or 30 car makers, only a few are early adopters — companies like BMW, Daimler, Audi — and they’re built in a way to do that. They have dedicated teams for working with companies like us, making sure everything goes right in such a complicated project. And that trend is even stronger when it’s related to functional safety.”

And Innoviz isn’t the only one getting buy-me notes.

“I’ve had three different acquisition opportunities cross my desk, just in the past week alone,” said Luminar’s Russell. “I think people are in many cases given a choice of after they recognize that the primary path was a bit of a dead end and that they need a pivot in order to survive. Oftentimes these are towards near-field lidar solutions, or to adjacent markets, or to even trying to just sell their company and technology get acquired by another larger company for talent.”

The investment profiles have changed as well. Fewer seed rounds for new entrants, more A and B rounds on companies that passed the sniff test. But overall there seems to be less cash flying around.

“The volume of investment last year and this year slightly decreased,” said Keilaf. “But last year you saw smaller investments in lots of companies, this year you see larger amounts in fewer companies.”

Everyone I spoke to agreed that the next year or two will see a “winnowing down” (three independently used the phrase) of lidar companies. Even if there are strong new entrants, we’ll see a net decrease, they suggested.

In other words, we seem to have reached peak lidar.

Climbing the tech stack for prestige and profit

With convergence, the strongest players get stronger. But that doesn’t mean the same thing for all of them — especially depending on who they acquire, acquihire, poach, or rescue from the ashes of a fallen firm.

With convergence, the strongest players get stronger. But that doesn’t mean the same thing for all of them — especially depending on who they acquire, acquihire, poach, or rescue from the ashes of a fallen firm.

As these companies grow, a major question for them is whether they want to remain a “lidar company,” or become something greater than that. There are risks on either side: Over-specialize and you become just a hardware supplier for a handful of partners, or get bought by a competitor; Over-extend, and you may end up competing with your customers, or building a product that falls short of the specializers.

The larger raises we’re seeing generally correspond to larger ambitions. But what ambitions are reasonable? Lumotive’s Colleran argues that many companies are going to spend a fortune chasing unnecessary independence or expansion.

“The reason some have raised a lot of money is that they want to do their own manufacturing infrastructure, which is obviously costly. We don’t think that’s the way to go,” he said. “There’s plenty of electronics manufacturing capacity, even with automotive qualification, out there. It’s better to partner with people who have that expertise.”

“Some are building AI capability to move up the software stack,” Colleran continued. “Again, there are plenty of companies with tons of AI software and experience that are developing autonomous systems. Does a sensors company need to vertically integrate in that direction?”

It’s a big task just to do lidar — why should we do the computer vision on top of it?

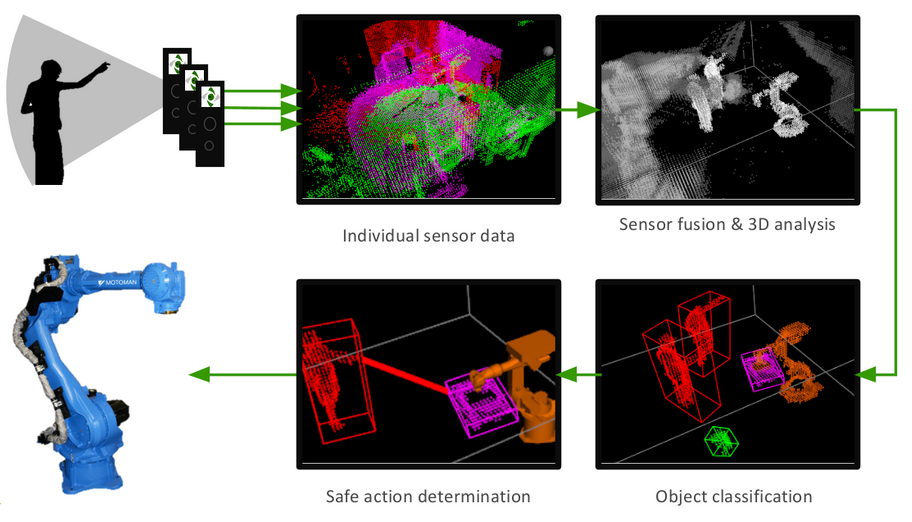

That question, in particular, is a serious one that nearly every lidar company has to grapple with at some point. It’s entirely possible that customers will want more than a point cloud and other raw data coming out of a lidar unit. How much processing should a company be doing on its own before passing it to the next system, be it a separate computer vision chip or the vehicle’s decision-making AI?

For some, it makes perfect sense because of the nature of their technology. Sense Photonics, for example, has a unique approach that makes some level of smarts both desirable and relatively simple to add. Because the receiver and an RGB camera can be mounted together, the depth data can be mapped directly onto flat image data, a capability many customers desire.

Sense Photonics makes it easy to match traditional camera views with depth data.

“We’re planning on moving up the tech stack ourselves, to be a full solution,” said Burroughs. “A lot of companies are looking for that. We don’t want to move up so far that we’re competing with our customers. But we can add a lot more functionality into the solution so it becomes more attractive and beneficial to them.”

Innoviz is already creeping further up the stack, and Keilaf’s explanation why is convincing.

“It’s a good question; We asked ourselves that when we started,” he said. “It’s a big task just to do lidar — why should we do the computer vision on top of it? That’s where our customers are going to go anyway.”

But in exploring the space the company quickly found that doing visual learning on 3D data is exceedingly difficult, and very different from approaches even experienced AI researchers would know.

“We learned that computer vision for lidar is very different. You can’t even find any good articles on how to do it,” he said (referring to journals and research papers, of course, not just searching online for it). “The algorithms are really new, we need to run it on a lean platform… it takes a lot of engineering to make it a product.”

“At the beginning, when we asked, companies said, ‘no, you do the lidar, that’s complicated enough, we’ll do the computer vision. Don’t worry about it!’ But we saw more and more companies come back to us and say, ‘you know what … let us see what you’re doing, let us play around with it.'”

These automakers and tier 1s were realizing that understanding lidar data wasn’t a trivial task — that to do it right, you need the kind of expertise and attention that only a dedicated computer vision company with native lidar experience could do. And they weren’t about to build their own at great cost when they already had one in their rolodex.

“In fact,” Keilaf added,” now you see some computer vision companies buying lidar companies just to get that understanding of 3D.”

He credited Innoviz’s native expertise in this domain as the reason they got the BMW contract, and the BMW contract was the reason they raised such a large round this year (both partly, anyway). That’s effective leverage.

Timing full production

The next step, most agreed, was deploying in a production environment — that is, real products on the road. No surprise there. But there were differing ideas on both timelines and markets. The most convinced of imminent deadlines was Innoviz’s Keilaf.

The next step, most agreed, was deploying in a production environment — that is, real products on the road. No surprise there. But there were differing ideas on both timelines and markets. The most convinced of imminent deadlines was Innoviz’s Keilaf.

“If an autonomous car is coming in 2021 or ’22, it will take them [i.e. automakers] three or four years to bring the design of the car to maturity and get it to production. So they need to make decisions today,” he said. “Startups in their A round now are going to miss that window.”

And when the next window opens up — by Keilaf’s estimate, in another four or five years when the next generation of cars is being prepared — it will be very difficult for a startup to compete. They might not even make it to the starting line. So in his opinion, the critical time is now.

Performance, economics, and scalability — whoever solves those three things wins the game

Luminar’s Russell says that despite his company providing units for testing and development for some time, there just isn’t a path to full production yet.

“Historically, no one has been able to put any of these types of LIDAR products into any production vehicle that can enable true autonomy. Nor has anyone historically actually had any type of roadmap to be able to successfully do that.

“Performance, economics, and scalability — whoever solves those three things wins the game,” he went on. “It’s also critical getting designed into these development fleet platforms so that people can really start developing their software on top of it, especially for those that could ultimately evolve into series production. A key thing for them is seeing the maturing of the product and company, from robustness to manufacturing process, to reliability, to repeatability of performance, to a point where the technology can actually be put into real production vehicles. That’s not a trivial thing.”

Nor will it happen all at once, or even in the next five years. Lumotive’s Colleran sees a much more graduated development occurring as the market moves from one surefire, low-risk proposition to the next. The first, he believes, is robotaxis: highly-specialized vehicles with a single purpose.

May Mobility’s autonomous shuttle.

“Full autonomy is a very strong business proposition,” he said. “They’ll get the best lidar possible. You’re replacing the driver in the car who you’d pay however much a year, so you can pay whatever you want. Of course, those robotaxis will be limited in their deployment, maybe even on fixed routes. From a lidar perspective, unit volumes will be lower but the selling price will be higher.”

It won’t be someone throwing a switch and saying ‘here’s our self-driving car!’ It’ll be hundreds of baby steps.

Consumer vehicles won’t come for another five to seven years, he said. And even then they won’t go fully autonomous but rather will improve driver assistance systems (ADAS). And production autonomous vehicles that an average buyer can afford won’t be available for a considerable time after that.

“These systems will start to get better and better, and become more and more capable,” he continued. “It won’t be someone throwing a switch and saying ‘here’s our self-driving car!’ It’ll be hundreds of baby steps.”

That gives lidar companies a pretty long timeline for bringing their solution to production. In fact, today’s integration styles may pass into disfavor as new multi-system (long-, medium-, and short-range) lidar setups become more realistic and affordable.

If the data guys get access to richer and richer data, pretty soon they can’t live without it.

Not only that, but other industries will be happy to keep the more modest companies afloat as they await the maturation of the automotive market.

“Every week that passes a new use case is introduced to us,” said Sense Photonics’ Burroughs. “As soon as the prices become affordable there are going to be markets that emerge that none of us will have thought of yet.”

“As you see capabilities evolving in the segment, resolution, scan rate, pixel rate, etc, you’re going to see use cases explode,” agreed Posamentier, the VC. “Then you’re going to see them latching onto the higher performance ones, and that will be a main driver for the winnowing. If you’re okay with a 64-laser spinning lidar, great, but if you can get high resolution, if the data guys get access to richer and richer data, pretty soon they can’t live without it.”

“As you see capabilities evolving in the segment, resolution, scan rate, pixel rate, etc, you’re going to see use cases explode,” agreed Posamentier, the VC. “Then you’re going to see them latching onto the higher performance ones, and that will be a main driver for the winnowing. If you’re okay with a 64-laser spinning lidar, great, but if you can get high resolution, if the data guys get access to richer and richer data, pretty soon they can’t live without it.”

That’s particularly acute in the case of lidar, because it ties into safety and awareness. If you could bump the specs on your sensing system and say you’re that much safer than the alternative, that’s marketable and maybe even could save a life down the line. It will be hard to cut corners in these systems once improvements due to better data are documented.

Responding to Musk’s anti-lidar views

On this topic though, it is worth touching on a recent comment by Elon Musk that perplexed more than worried the industry.

“Lidar is a fool’s errand. Anyone relying on lidar is doomed. Doomed!” said Musk at a Tesla event showing off some new computing architecture. He called lidar “expensive sensors that are unnecessary. It’s like having a whole bunch of expensive appendices. Like, one appendix is bad, well now you have a whole bunch of them, it’s ridiculous, you’ll see.”

Few of the CEOs seemed bothered by this dire prognostication.

“I don’t think anyone really knows what goes on inside Elon’s head, but he’s a really smart guy,” ventured Burroughs. “But from the standpoint of needing or not needing lidar, we’ve looked into it quite a bit. And it’s fair to say that all the auto OEMs have done the analysis and concluded that lidar is necessary. All the ride-hailing companies have come to the same conclusion. All the AV companies have come to the same solution. Cameras and radar alone aren’t enough.”

It seems that Musk’s comments are not unreasonable, however, when viewed strictly as an evaluation of the current market and the viability of using it in a production vehicle.

“Let’s be candid, lidar is unaffordable in consumer vehicles,” said Colleran. “But if a lidar unit were available today that had good performance and was affordable, it would quietly show up in a Tesla car and this whole hubbub would go away.”

The light industry gets heavy

Lidar’s position as a key sensor in autonomy seems cemented — but that’s about it. What type, what size, where on what model, and for how much, all these variables are in flux as practically everyone involved in the nascent autonomous vehicle market (alongside the already formidable industrial automation market) husbands the startups of the industry, tasting but never taking a bite.

The best-laid plans of any AV concern or full-stack sensing startup could be toppled by regulation, a technical oversight, or a fatal accident. Just ask Uber.

And after two years of expansion and open wallets, slip-ups and strategic mistakes at this stage may not be able to be fixed with a bit of cash and six months of extra dev time. Lidar has entered a sudden-death phase where those that fall will be quickly devoured by the competition — yet at the same time, it’s clearly too early to pick winners.

The companies featured embody different techniques and philosophies, and having stated them clearly at what may be considered a watershed moment (or period at least) in the industry’s history, we may better judge the outcomes when inevitably, one, or two, or all of them ascend to higher glory — or succumb to a defeat that will seem obvious in hindsight.