Since 2013, SparkLabs Group has invested in more than 230 companies, and my general advice to our founders and portfolio companies hasn’t changed: I always tell them not to overthink valuation, know what they need in terms of capital for their seed round and how there is “good dilution” and “bad dilution.” Whether your dilution ends up being good or bad (or ugly) generally depends on how well you execute.

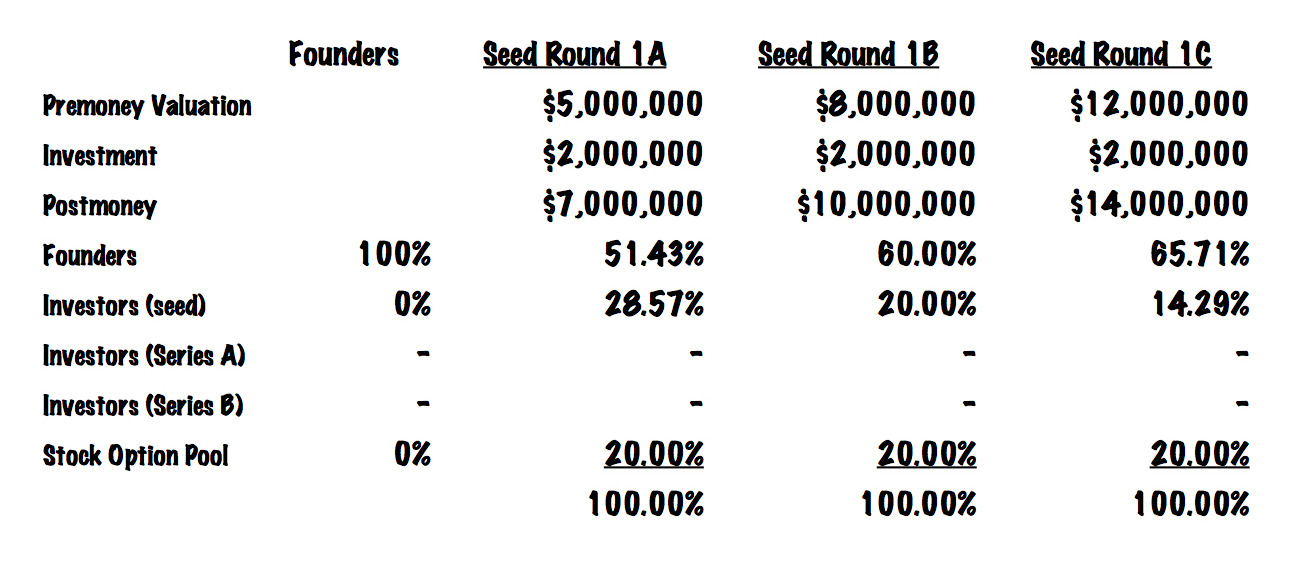

To solidify my advice, I sometimes go through the math of possible seed rounds and how future rounds can play out. To keep the discussion simple and focus on my core points, I keep the amount of investment the same and assume the company is starting with a 20% stock option pool, which venture capital firms typically require by a startup’s Series A round.

Three scenarios

I map out three valuations, representing a standard Silicon Valley startup with a pre-money valuation of $5 million (Scenario “A”), a “hot” startup with an $8 million pre-money valuation (Scenario “B”) and an outlier with a pre-money valuation of $12 million (Scenario “C”).

Let’s look at the typical pathway where the founders raise a $2 million seed round on a pre-money valuation of $5 million. They build their product, launch, gain great momentum and successfully raise an $8 million Series A, where even though they don’t get that many lead interests, they get a decent $20 million pre-money valuation.

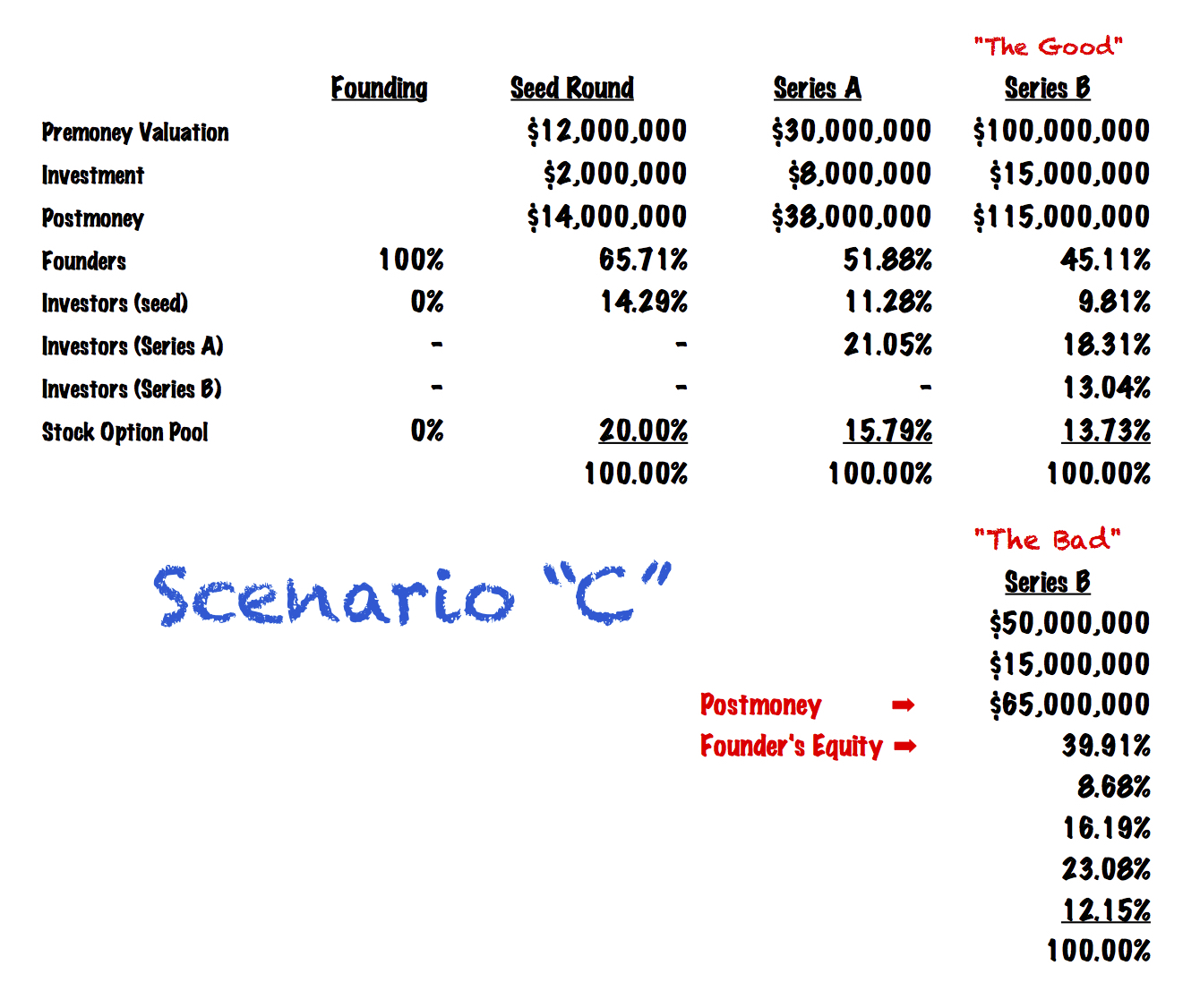

Let’s assume this startup is in a mature startup space where investors are looking for good revenue traction. With the $8 million raised, a startup team can face “The Good,” which I define as executing on all cylinders, or “The Bad,” which I would define as a struggle.

Sometimes it’s not about executing poorly or mismanagement. A product can be too early, deal with longer than expected sales cycles or face other factors outside a startup team’s control. Regardless, “The Bad” situation can be where a company isn’t able to raise their Series B at all — or struggles to find investors that still believe in the product and team, and gets funding but not at the best valuation for the founders and team ($15 million raised on a post-money valuation of $50 million).

“The Good” would be a startup hitting traffic, revenues, clients sales or whatever metrics help drive success. Here the same startup raises a $15 million Series B on a post-money valuation of $95 million.

Scenario “C” was the startup with the outlier valuation at their seed stage that raised a $2 million seed round with a post-money valuation of $14 million. Probably a company founded by a co-founder of Twitter or a hot YC company. Their Series A continues on a similar trajectory, raising $8 million with a post-money valuation of $38 million. Their fork in the road is similar to the prior situation. “The Good” is a Series B that raises $15 million with a post-money valuation of $115 million, while the “The Bad” raises the same amount but has a post-money valuation of $85 million, and the founders owning 39.9% of the company versus 45.1%.

Don’t overthink or overplan your fundraising rounds

The easy conclusion is that it is really hard for founders and a team to predict and plan their fundraising rounds over the next several years, much less how well their product will turn out.

But you can make sure you’re better prepared as entrepreneurs by asking yourself some basic questions:

- How much capital do you really need to last you 12-18 months?

- Will this amount allow you to hit milestones to raise your Series A or Series B?

Some startups don’t need much capital to take off, while others need more. An entrepreneur’s problem can be raising too little or too much capital.

During my second startup in 2000 — during the first internet boom when money was flowing easier than today — we raised $7 million as our first round. I would describe that experience as “big rounds are like meth for entrepreneurs,” which typically ends in “The Ugly.” Money burns quicker than most entrepreneurs think. It’s not paper, it’s paper soaked in kerosene. Luckily, while facing bankruptcy, we closed an additional $7.5 million and the company became profitable — but not without a lot of pain and torment.

We have seen a fair number of our founders underestimate their cash needs at the seed round. Then they have to raise additional seed capital, which isn’t easy. Some might have been too confident in their sales ability or how efficient they would be with their capital. Investors might assume those were issues, plus question whether the market is really there, or whether the management team made too many missteps. Be prepared to answer these types of questions if you need to raise additional seed capital.

Pitching the valuation game

We typically remind our founders that the best way to increase their valuation is to execute well and gain enough interest to be offered at least two term sheets.

If you are raising a Series A and your seed round was a convertible note or a SAFE, that cap really isn’t your valuation, so don’t get fixated on that as a minimum. We’ve had portfolio companies with valuation caps of over $30 million pre-money, but their Series A was priced above $20 million. We’ve also had a founder overzealously focused on their valuation cap from their seed round on, who ruined negotiations with a top 10 VC firm because they wouldn’t go lower than their cap.

If you have one potential lead, I generally recommend knowing your value and negotiating reasonably. If your lead lowballs you, of course you should walk away. But if it’s within range, don’t nickel and dime on the valuation.

Your goal is to create investor interest from multiple firms while generating the least amount of friction to quickly close your round. It might be a difficult balance between knowing your value but respecting what investors are looking for, but don’t kill your fundraising efforts by not being flexible on valuation. Remember, it’s not all about the money and your ownership percentage. If one of our portfolio companies had a term sheet for a $10 million pre-money valuation from an unknown family office or an $8 million pre-money valuation from a top-tier venture capital firm, we would tell them to take the lesser valuation, even if it’s a smaller gain on our books.

Although raising money while navigating dilution can be tricky, with the right preparation and mindset, it’s possible to close your round with the best value for your company.