Technology is very much in the business of, quite literally, changing the world. When I was deciding whether to write for TechCrunch, I tried to imagine a human life on this planet, in 20 or 30 years, that would not have been dramatically impacted in one way or another by the new technologies we’re creating today.

I couldn’t picture such a person, so I decided this ongoing series on tech ethics was the right thing to do with my time.

Below is the second part of my interview with Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, a brilliant young author, activist, and the first Black woman in history to hold a faculty position in theoretical cosmology.

Her work critically analyzing the politics of the science world seems particularly salient to the tech world generally and to the world of tech ethics in particular: for example, Stanford recently launched an enormous new initiative in ethical technology, the “Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI),” which boasts plans for a billion dollar investment in making AI “representative of humanity.”

Yet among the 121 HAI faculty members initially announced this March, it has been much discussed that the overwhelming majority were white, most were male, and not a single one was Black. In part one of my dialogue with Prescod-Weinstein, we discussed decolonization and intersectionality; here I’ll begin by asking her about inclusion.

Greg E.: How is the science world doing, in terms of creating an inclusive culture?

Chanda P.W.: I’ve got mixed feelings about the question of inclusion. We need to ask ourselves what our aims are and where we’re going with this. I don’t necessarily think that tokens solve the problem.

I want to be clear that when I say tokens, I don’t necessarily mean that the people who end up in these rarefied environments, like I’m one of only two black women in the College of Engineering and Physical Sciences at University of New Hampshire.

Image via Getty Images / Jon Feingersh Photography Inc

I would never degrade the efforts of my colleague, the other one. And how hard she had to work to get to where she is. I know her. She has an impressive intellect. She’s an extraordinarily committed teacher. She’s absolutely earned where she is and then some.

I won’t make those same comments about myself, but I will say I think I worked pretty hard to get to where I am. But I also think that at least in my case, I’ve lived the life of a highly successful token.

For me the question is not how do I get one or two through the door, but how do I create an environment where people who want to be present are present. This is something that I’m thinking about a lot as I’m working on my book, which talks about all of the ways that I live with my science.

I am [trying to write about] my science in a way that says to people from the communities where I grew up and the communities that I am a part of, so to folks in the black community, to folks from east LA and in particular, El Sereno, which is where I grew up, that this is a book for you and that popular science books aren’t just for nerdy white kids, they’re also for nerdy black kids and nerdy Latinx kids.

Greg E.: A lot more kids in those counties that would be nerdy if they were given any kind of reasonable permission to be.

Chanda P.W.: Right. And if it was said that you are allowed to manifest. I think that for me, that’s an interesting question, is who is allowed to manifest, in their fullness of who they are and what thoughts they are interested in having and might have if there weren’t barriers associated with our ascribed identities?

I do think it’s important that the numbers reach parity. If black women make up 6% of the U.S. population, then they should make up 6% of the physics faculty in the United States. We’re at something like 1% maybe. So we’re pretty far off.

But equally important is how do we envision what our relationship and role in the community is as academics. Is the goal to get a certain number of representative people into positions of power who are part of an elite ruling class?

This goes back to my thinking about, what am I doing at Harvard, as an undergraduate. Am I joining the ruling class, or am I getting an education, or am I doing both? I was trying to get an education without joining the ruling class.

I actually found that to be a really challenging experience. Because I wanted to talk about the bifurcation of those two things and a lot of other people were really uncomfortable with that conversation.

I have no interest in reifying the ruling class and making it more colorful. If I was gonna talk about disruption, I wanna disrupt the idea that we need people on top and people on the bottom.

Greg E.: Wonderful. That last paragraph was a perfect example of what I am hoping to explore in this series. (My first piece, with author Anand Giridharadas, explores similar questions).

Image via Getty Images / Nick Lowndes

I think I’m hearing a concern on your part, which I think I share, that a lot of what we talk about when we talk about science and tech today is the creation of a ruling class.

Chanda P.W.: Yes. And what’s interesting about this is sometimes the concept of Silicon Valley is offered as some kind of panacea, like it’s going to disrupt traditional power frameworks. [But] just look at the impact that it has had locally of the inability of people to find housing.

I have a friend who, I would say, is pretty well paid at a big tech company that I won’t name. He makes way more than I do. In fact, until fairly recently when I started this faculty position, he was making more than twice what I was making, even though we have the same training. He is never going to be able to buy a house anywhere in the Bay Area. I’m laughing because that’s ridiculous.

Where does equality come into the conversation when highly paid employees who are the engine behind this machine are unable to do what used to be everyday middle-class things? I actually think what we’re seeing is a hardening of the hierarchy rather than a disruption of it, although maybe we’re seeing a disruption of how you become part of the hierarchy or how you end up at the top of it.

Greg E.: Maybe some of what we’re seeing is a disruption of the disruption. As the world began to become more global and as a non-white, non-male majority was beginning to emerge in this country, for example, and as we were beginning to rethink certain aspects of our colonial or violent heritage in this world, maybe some of these disruptions have actually interrupted that process and are now keeping power in the hands of fewer than otherwise it would have ended up in.

Chanda P.W.: Yeah, I think a fantasy people sometimes tell themselves to get them through the day is, ‘what I’m doing is okay; I’m making the world a better place because I’m developing technology that makes it easier for people to communicate. It makes it easier for people to get into a taxi or a taxi-like vehicle.’

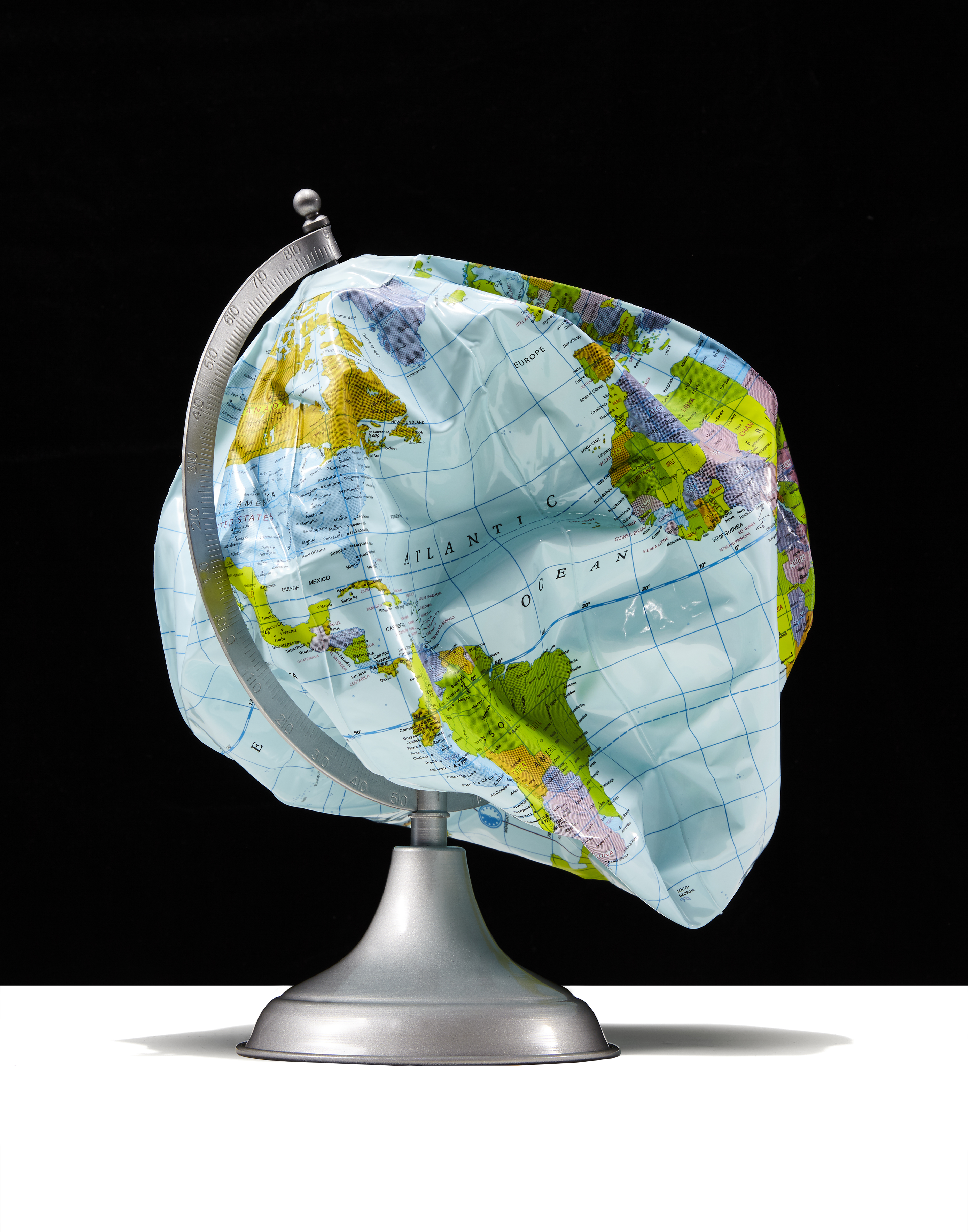

But which people? It’s rooted in this foundational concept that technology always makes things better, but I really like to remind people that global warming is a technological development.

Greg E.: Missiles are a technological development.

Chanda P.W.: Missiles are a technological development. Maybe [some] people think missiles are a good thing. But everybody, for the most part, is on the same page that global warming is a bad idea for earth. [Yet] it is also a phenomenal symbol of our technological prowess.

Image via Getty Images / Shana Novak

It also proves technological evolution is not always social progress, because it’s clear that global warming is a disruptive technological development, for the worse. On the other hand, people who were thinking about colonizing Mars, they’re probably really interested in this global warming thing because that’s certainly something that would be needed to be done on Mars, to make it more habitable.

…Do I have anxiety about that comment possibly being published and giving people ideas? Yes.

Greg E.: I’ll go one step further then, just so you’re not alone. I think a lot about how global warming is superb for Russia. I mean, Chanda, we’re all gonna be living in Siberia in a few decades.

Chanda P.W.: Right. I mean I just read the LA Times had a great article about the Yakutsk punk scene just a couple of days ago, so maybe we’ll have a super awesome punk scene because I really think that American punk has been in trouble for a while. As sort of an old punkhead.

Greg E.: Did you know that in Birobidzhan in Siberia, which is where some of our Jewish ancestors would get banished to if they were a problem for the Soviet State, there are now Korean Yiddish teachers there who are responsible in many ways for preserving the development of the Yiddish language?

Chanda P.W.: Oh, I didn’t know about that particular intersection. I was aware of the Korean ethnic community in that region because I saw a really phenomenal art show at one of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art locations in Seoul a couple years ago; I spent a lot of time in Korea.

One of the artists that they kind of did this lifetime show on was someone who would now be considered to be from North Korea, who spent most of his life in what was called the Soviet Union. I learned a lot about the ethnic Korean community there.

Actually, the reason the Yakutsk article stuck out to me was because pretty much all of the people in the pictures were people we would identify in an American context as being Asian. So I saved it to show to my husband, because he’s Asian American and I was like, look at all of the central Asians.

There’s a whole conversation about race in Russia that we’re not having that I think we’re going to have to have soon. That’s a totally different topic, but I think there’s a whole conversation there. That’s really interesting about the Yiddish Korean teachers.

Greg E.: Korean culture apparently has had a real fascination with the Talmud as well, but let me bring us back from this digression for a couple more questions.

You’re living on Twitter right now in a way that few people are; few people get to see what it’s like to really be a prominent, vigorous, energetic activist on Twitter where you’re tweeting all the time and you’re having really controversial conversations, or at least conversations that other people view as really controversial all the time. About being a black Jew in science, being agender, etc.

What’s that like for you, and how are you feeling about all the time you’re spending on Twitter? Does the dialogue we’re all investing ourselves in, there, seem worthwhile?

Image via Getty Images / Gary Waters

Chanda P.W.: My feelings about Twitter are really complex; it’s a great place for black scientists to find each other and get to know other black academics or “blackademics” as we often call ourselves. [Those are] key reasons I’ve stuck with it.

I also think Twitter has done an absolutely abominable job of managing the amount of white nationalist, white supremacist vitriol that goes on on the network.

Juxtapose this with how they’ve handled the Islamic State’s presence. They actually went out of their way to get that under control, but they don’t feel the same kind of pressure with white nationalists because some of them happen to be elected officials who are members of the Republican party. I also just think we should also worry about Jack because apparently he only eats once a day or something like that and that’s really unhealthy. There are all sorts of weird stuff going on.

I’m also very concerned that we seem to be almost dependent on this network that’s privately owned, where there’s no regulation of what happens to our data and all these things. So it’s a mixed bag.

At the same time, it can be very hard to get people to go and read a blog. If you want to offer commentary to people, Twitter threads are one of the best ways to do it. It’s a lot harder to actually get anyone to read [a blog] besides emailing my mom and being like, ‘mom, can you read this?’

So for me, Twitter is a place where I exchange ideas with people … in the best case scenario. It helps me think out loud. I’m able to see what kinds of ridiculous responses people have to things. This morning, I made a comment [that] black Christians are influenced by a tradition of antisemitism that was inherited from white Christianity.

Someone was like, ‘you’re overgeneralizing about Christians and that’s not fair.’ And I’m like, ‘we’re a few days out from a white Christian nationalist shooting up a synagogue so maybe today’s not the day to be complaining about Jews being unfair to Christians.’

Actually, my feeling is, it’s too early in the millennium. Give it a few hundred years and some massive social changes. Also, in practicing articulating my objection to the comment [above], I have practiced articulating myself. That’s a useful skill to have.

Greg E.: Speaking of useful skills to have, I think that if anybody is feeling triggered or challenged by this conversation, they should just follow you on Twitter. Maybe even give themselves an alert for your tweets for a couple days. They’ll get to read all of your tweets and just monitor their blood pressure and breathe and think about the things that you’re tweeting about.

I think that would be a great exercise for people. One does not need to agree with you 100% of the time to learn a tremendous amount and be provoked in thought by your writing. They should also buy your book (in 2021), The Disordered Cosmos: From Dark Matter to Black Lives Matter.

Image via Getty Images / Caiaimage / Trevor Adeline

Chanda P.W.: I’ve written this long tirade about quarks but there are also discussions about racism in science. So if you’re interested in a book that talks about quarks and dark matter and also how race and gender shape science, then my book will be the book for you.

Greg E.: Last question: how optimistic are you about our shared human future?

Chanda P.W.: It really depends on the day and the week and the month. I’ve dealt with enough questionable things in academia that I am not optimistic that academics will be the solvers of the problem. Although I do think that many academics may be able to play a role.

I think humans are more competent than we think we are, even though sometimes we overestimate ourselves, we are competent in ways where we underestimate ourselves. So I’m going to place my bets on that. I have to because I don’t have kids, but my friends do and I love their kids.

So I just have to keep thinking it’s possible, whether or not I feel optimistic about it at any given point. I have to choose to believe that and work toward that on the off chance that I’m right.

Greg E.: Beautifully said. Thank you. Chanda, this has been a real privilege for me, probably in more ways than one.