Soaring college tuition prices have left Americans drowning in debt without a correspondingly enhanced set of professional skills to show for it. In the past 11 years, US student debt has increased by 157% and 1 in 10 borrowers are over 90 days delinquent.

Universities are incentivized to be unaffordable and don’t have a direct financial interest in the outcomes of their students. The average budget for career services at colleges is $90,000 including salaries, with only one career counselor for every 2,900 students on average.

Income share agreements (ISAs) have been developed as a financing model that could reshape the way education programs operate by aligning interests while expanding access to those programs and limiting payments only to what graduates can afford.

Lambda School may be the most notable startup advancing this model, having closed a $30 million Series B in January. But ISAs are neither simple to implement nor uncontroversial in policy circles.

Last week, I attended the first Life Capital summit, which convened the small (but growing) group of education administrators, entrepreneurs, investors, and policy experts who have been active in this movement. Slow Capital’s Sam Lessin organized it alongside Village Global and it attracted investors from a number of top VC firms given the wave of education and fintech startups that will arise if ISAs go mainstream.

An ISA is essentially an equity alternative to private student loans. An investment fund — which could be the school itself — covers tuition for students in exchange for a certain percentage of their income for x many years after. These almost always have a minimum income threshold before they kick in and a cap on the maximum total return.

The conference sparked a conversation about ISAs between Extra Crunch’s executive editor Danny Crichton and I. We talked about how ISAs work, misconceptions, the potential positive and negative impacts of adopting them, the dynamics of ISAs as a new asset class, the politics of ISAs, and the startup opportunities that result from this.

Here is our edited transcript:

Impacts on education

Danny Crichton: I see three angles here in terms of evaluating the ISA concept: educational institutions, investors, and politics. Why do you find this to be a big deal for education? Is it more about access or about incentive alignment?

Eric Peckham: It’s both. And about ensuring that the decision to get better educated doesn’t sink you financially if you hit a rough patch later where you aren’t making much money.

Expanding access to education is central though. Only accredited college degree programs are eligible for federal student loans. Vocational boot camps that train you on a specific skill and place you in the job market require full cash payment or financing entirely through private student loans (which have much higher interest rates). Expanding this boot camp model to more disciplines would be beneficial both to individuals who participate and to the economy overall.

If you hear “college student” and think of 19 year-olds from the suburbs who are attending Berkeley full-time, know that’s not what a huge percent of college students look like anymore either. It’s part-time attendance, it’s single mothers, it’s adults who worked for a few years after high school, it’s online degrees, etc.

A lot of people don’t have access to private student loans at reasonable interest rates and thus can’t afford college or grad school programs that they should be participating in to advance themselves. Their family is low-income, their past personal financial troubles hurt their credit score, etc. And even if they do get loans for an education program, the amount of debt they take on often doesn’t make sense for the career outcomes of the program.

Danny: And then the incentive alignment will make colleges more pre-professional?

Eric: Incentives drive behavior. The financial incentive of higher ed programs now is to get students in the door and collect the upfront tuition dollars from the loans they’ve taken out. If the incentives were aligned around students getting high paying jobs and successful careers after graduation, that would be a radical shift to reverse much of the cost disease in colleges. ISAs reward institutions that are effective at educating their students and do so in a cost-effective way.

If ISAs go mainstream, you’ll see a wave of entrepreneurs starting (non-profit or for-profit) education programs that are much better ROI for career success in a certain field than traditional colleges. More serious training, fewer $20 million gyms.

But many universities are also testing ISAs as an alternative to private student loans. That means it’s only a small amount of their revenue model, but even then it creates a shift in mindset to think more about what career advantages students are getting for the money spent. To say universities don’t prioritize career services today is a massive understatement–the budgets show its a complete afterthought.

Danny: This could also change the calculation for many people on whether to start a business or otherwise leave a stable job in order to pursue an opportunity with a longer-term payoff.

Eric: Indeed. Owing hundreds (or thousands) of dollars in monthly debt payments inhibits many talented people from starting their own business. I don’t just mean tech startups but all entrepreneurship in the economy. It likewise blocks people from taking a lower-paying job that has a better long-term payoff, like a prestigious internship or fellowship program.

Image via Shutterstock / Volhah

Danny: Flat monthly payments are tough for people who don’t have flat monthly income. The whole sharing economy.

Eric: What is it, a third of Americans that now work as contractors or juggle multiple part-time jobs? There is a lot of income volatility. And people change jobs much more frequently today than they used to. Especially early in one’s career, there’s a lot of uncertainty.

ISAs can eliminate some of the downside risk where if you’re not making much money — like you need to work at Starbucks after graduating because you’re having a hard time finding a job in your field — you don’t have to pay or you only pay a small amount. That’s pretty powerful. With traditional loans, even income-based repayment plans, there’s no escape from that debt, even in bankruptcy. You’re not on the hook to pay forever. Once time elapses, you don’t owe more even if you didn’t pay back the basic tuition price.

Danny: Given the caps on upside, ISAs are not really trying to create a power law distribution, right? Like Harvard’s not going to benefit a lot because it has the next Mark Zuckerberg.

Opportunities for startups and investors

Eric: When you see people talk about this on Twitter they frame it as like venture capital or angel investing for individuals. And that’s not what it is. I mean, you could approach it from that perspective. But none of the programs out there that I’ve seen are doing that and most likely there will be regulation that prevents you from doing that. It’s pretty standard that these have a cap on the total amount of money that can be earned back – somewhere in the 1.5x to 2.5x range.

It’s not about making money off one outlier student, it’s about investing in all the students who are part of a certain program – a class in a university or a software development boot camp. Within that portfolio, some students are financial losses and some of profitable, and by diversifying your risk you hope to net a stable return. The better the education program, the better market terms for ISAs.

Danny: What are the frontiers of this? Where is it being tested and what were the attendees at this summit most focused on?

Eric: You have two areas where this is being tested out. One is in traditional universities. Purdue in Indiana has led the way there. In those cases, the university is funding it themselves or partnering with an outside servicer like the startup Vemo Education who designs the program and helps them raise the capital. Vemo’s CEO said they will have launched 50 programs with universities by the end of his year.

Traditional universities are viewing ISAs as an alternative to students having to take out private student loans once they’ve gotten the maximum amount of federal student loans that they can take. That’s the use case here. Purdue isn’t doing ISAs for the entire degree. We won’t see that anytime soon.

Danny: What’s the second area? All of the coding boot camps?

Eric: Yes on the other side you have these boot camp models. These coding schools like Lambda, Make School, and Holberton use ISAs as the business model for the entire program. They’re trying to take people who are making like $40k a year and in the span of six months or two years turn them into software developers who make $120k a year. That income delta is not representative of broader use cases for boot camp, but the model could be applied to tons of in-demand job categories.

Danny: Assuming the politicians pass supportive regulation and ISAs become more common, what are the startup opportunities that result from it?

Eric: Well the first category is education programs. All of a sudden there’s a direct business model for creating high-quality training programs for people to enter new fields or advance in their fields. Every discipline where there is a skills shortage.

You’ll also see a wave of career guidance startups. Think career services at a university but a) actually done well, and b) ongoing for many years. Perhaps its a service that directly charges with an ISA or maybe it partners with education programs that give it a stake in the ISAs in exchange for handling the job placement and career guidance work.

On the finance side, you’re already seeing a number of startups that provide the infrastructure for ISA programs to educational institutions or that act as the investment partner. Some of these are consumer-facing, offering the ISA model directly to students without going through the institution they’re in. There’s a huge need for analytics here to build the financial models that inform terms of ISA agreements, which presents a business opportunity.

Danny: The student loan market is one of the largest asset classes overall. It’s a $1.5 trillion market, albeit 95% or whatever is federal dollars [ed note: federal spending is about 92%]. Obviously, students are far more diverse than the kind of loan programs we have available. What’s interesting here is you’re starting to see the creation of a new approach. It may not be right for all students, but in a universe of a trillion dollar plus loan book, can there be $100 billion that might go under income share agreements? My answer is yes. Almost certainly.

Eric: I think there’s huge potential for this market. We’re still so early. And there are fundamental questions, both from a business perspective in terms of students and educational programs and the right way to do this, but also in terms of regulation and how is this market should be allowed to develop. Maybe the government will pilot ISAs directly. What is clear is there’s interest from a meaningful subset of education programs and students who are willing to try this.

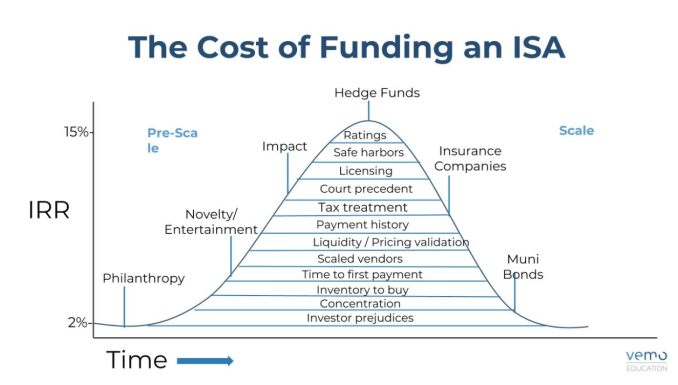

Danny: One of the big questions that is still open in my head is what does the IRR look like here? When I was an undergrad, traditional student loans were like 4% or 5%, I think, not 6% or 7%. Nonetheless, there’s this nice fixed rate. And even more importantly, traditional student loans are not dischargeable in bankruptcy. That’s unique for student loans compared to any other form of loan obligation.

Eric: The short answer is that it’s too early to answer that with much data. It’s a critical question though because we’re talking about the creation of a new asset class. If the risk-adjusted returns aren’t there then the capital markets won’t open up.

ISAs are higher risk when spread across a smaller number of people and when there’s little track record and the regulatory risk of not yet knowing what law may pass on this. The whole market right now is a few thousand students not millions of students. The capital going into this currently is from philanthropies, impact investment funds, family offices, and student lenders who are hedging in case it disrupts them. I know a couple small hedge funds in it specifically because of the risk but traditional finance is still just watching.

Tonio DeSorrento, the CEO of Vemo, put up a great graphic at the conference. It’s a bell curve outlining how IRR will increase as more of the infrastructure and regulation of ISAs comes into place, then how it will naturally decrease again with massive scale due to predictability and downward pressure on ISA terms (in favor of students). Hedge funds will enter as this explodes, then it’ll shift to insurance companies and similar large institutions as the main financiers as it matures into a stable, fixed-income asset class.

Image credit: Tonio Desorrento, Vemo Education

From the student perspective, this is about the cost of capital. How much could you end up paying via ISA in order to get your tuition covered, relative to how much you’d end up paying via loans to cover the tuition? The more data and infrastructure there is for the ISA market, and the more scale it has, the lower its pricing can drop. It can’t compete with subsidized federal student loans but it could become cheaper than private student loans in some instances.

Danny: There’s also a global macro problem where a lot of people go back to school during recessions. And so that’s exactly when the demand for ISAs will increase, but that’s also precisely when the investors are going to step back from the student loan market due to their own lack of liquidity. So I think that’s going to be a huge question as this ISA market develops. How do you handle that counter-cyclical demand for student loans?

Eric: From an investor perspective, ISAs will be cyclical. When there’s a broader economic downturn, incomes of people using an ISA will decline on average. Same problem as with traditional student loans here. Expect that ISA agreements signed during a downturn will have longer terms (and perhaps lower percent of income).

You could have this whole asset class with ISAs that is directly tracking the income of educated Americans. It’s pretty fascinating in terms of having the ability to invest in the American worker and their productivity, or on the other side, shorting that if you thought a recession was coming. If this becomes a massive market then there will be a lot of interesting financial products created around it. Like we saw with mortgage-backed securities though, I’m worried that if the education programs and investors agreeing to ISAs are reselling them as a bundle to larger investment firms then you lose some of the incentive alignment that’s supposed to come out of this.

Policy concerns

Danny: How do you address bias here? The discrimination between students that will naturally arise.

Eric: The way to address discrimination is the same as with student loans: regulation. Like prohibiting gender as a factor in terms. Everyone I’ve spoken to in the ISA space assumes the same anti-discrimination laws for student loans will apply here and are operating under that assumption. You can make a legal argument that ISAs already fall under student loan discrimination laws, and no one wants to get sued. We need regulation here though.

That said, let’s keep in mind that with the incentive alignment of ISAs, you’ll have education programs competing to be the most effective at helping disadvantaged groups of people rise up to better living standards and rewarded for doing so. Competition here will result in better and better programs at terms that are ever friendlier to students. It’s the opposite of these scandals we’ve seen many times of schools preying on low-income Americans and veterans with high-priced, low-quality programs that just aim to get the upfront money from loans or GI Bill payments.

Danny: How do you sort out the moral hazard that comes with this? The adverse selection? If I know I’m going to make a lot of money out of school, I wouldn’t want this, and if I expect to not make much I’d be eager to sign on to it.

Eric: Mary Claire Cartwright, a VP from Purdue University, said at the conference that they had an economist analyze the three years of data about their ISA program to identify adverse selection and he didn’t find any. The proportion of ISA students who were Pell Grant recipients, first-generation college student, in-state/out-of-state, and male/female all matched the student body overall and there’s a fairly even distribution of majors. (She did note that Hispanic and multiracial students over represented.)

Adverse selection is an open question in this space. It came up a lot during the conference. With boot camps it’s more straightforward: often the only way to participate is through an ISA and they offer a type of professional training that isn’t widely available elsewhere. They’re also specialized to career ambition, unlike most universities. You’re not gonna find many people in a software development boot camp who plan to become actors or social workers once they graduate. A boot camp for acting or social work would have to be run in a cost-effective way that makes sense for the expected income in that field.

One issue that came up here is that when ISAs are explained to students they focus a lot more on the payment cap than the downside protection. Everyone assumes they won’t be the one to drop out of school or run into a financial rough patch. If people aren’t valuing downside protection as a premium benefit of ISAs compared to loans then they won’t go for it. An ISA is like an insurance policy: you could end up paying more than you otherwise would but you’re protected if you end up not making much money.

Image via Getty Images / VLADGRIN

Danny: You’re making a bet on students who are engineers and not liberal arts majors. Would I have to pay a lower income share if I took a certain major versus another?

Eric: That depends. Purdue does set different terms depending on major, other colleges testing this don’t. It is rational to give better terms to an engineering student than an art history student when you look at average income post-graduation. The question for each program to decide is whether they believe that difference is good or bad. I believe it’s good: it causes students to reflect on the real-world implications of their decisions and weigh the cost/benefit of different career paths. Variable tuition based on major is quite common outside the US by the way.

This also drives healthy competition for education within a given career field. I just Googled next year’s tuition at Tufts where I went to undergrad. It’s $57,000 without financial aid. $76,000 with room and board. If terms for an ISA on that as a music major aren’t attractive, well that’s because it’s probably crazy to spend that much on that education if you’re planning to be a musician. If you consciously decide it’s worth it for the social experience, and the gym facilities, and the broader liberal arts survey of courses then great. But you’d be better served in a specialized music program that’s lower cost if your priority is to prepare for a certain career path and you’re not wealthy. These are all healthy wake-up calls.

Danny: Do we know how people are handling both the regulatory and political aspects of ISAs?

Eric: The biggest question in this entire space right now and the variable people are most concerned about is the political risk as opposed to the business challenges.

You have something here that’s actually bipartisan in nature. You’re talking about using market forces to expand access to education, fight predatory private student loans, make schools accountable for offering a quality education. And it places the risk on investors as opposed to on students. This alignment of both Republican values and Democratic values is pretty fascinating. But at a time like this, bipartisanship is definitely against the grain. Everything is just a political football to attack the other side. There’s a lot of risk here. If it gets framed as a Republican idea then the Democrats automatically attack it, and vice versa.

Danny: What do the next couple of years look like for this ISA movement?

Eric: There’s a surge of interest in this space. I can tell you a year ago, when I called dozens of people to research this, the only people serious about this were a handful of education startup folks, a few small investors, and a few think tank researchers. It’s really taken off. More VCs have taken an interest. Lambda School has attracted a lot of attention to it with its big fundraise and with its founder Austen Allred — who has 100,000 followers — sharing student success stories on Twitter. There are more and more entrepreneurs who are looking at this.

This isn’t is a billion dollar market in the next couple of years. There’s clear momentum though. Higher ed is all about social proof… colleges wait to see others adopt something new and wait until they feel pressure to do the same.

The biggest question that everyone has is around what’s going to happen in regulation and politics. And that ultimately comes down to how well ISA proponents can educate key stakeholders about what this is and how the right regulations can make it impactful.