How do you know your product is priced too low? One way is when you raise the price between 13 and 18%, you have almost no churn, not many complaints, and your stock price actually goes up!

When Netflix increased its prices a few weeks ago, investors were so confident in the revenue increase that would be delivered that they didn’t even wait to see what customer’s reaction would be.

Netflix spends an astounding amount of money on content rights and content development — supposedly budgeting $15 billion for 2019 — and resulting in $3 billion in negative cash flow, which is heavily funded with debt — at $10.4 billion by the end 2018.

Even at its already large size, the company continues to grow rapidly, so I am not suggesting their cash flow or spending is any cause for concern.

What I am suggesting is that Netflix is too cheap, and could likely be cashflow profitable without reducing investment in content, by implementing some pricing model changes. The fact that customers and investors did not seem to bat an eyelid at the recent price increase gives me some confidence that they are not maximizing profit per customer!

In some scenarios, especially early on, companies decide to focus on customer acquisition at the expense of revenue maximization. Other than the unfathomable madness of some companies that do this while running a negative GROSS margin (a big ‘thank you’ to their investors for subsidizing consumers!), market share ‘land grabs’ in B2C can make sense. It looks like Netflix has been focussed on market share for a long time and continues to focus on maximizing subscriber numbers over profit.

But is it really a linear equation — where an increase in price will result in a decrease in new subscribers or total subscribers? Clearly not in this case. Wouldn’t it be worth at least testing variations on the pricing model in somemarket segments to discover the optimum value price?

Quick definition — the Optimum Value Price is where you can capture the highest number of customers, at the right price for each type of customer.

Right now — Netflix differentiates price in 2 ways only — number of screens, and HD or Ultra HD. I think Ultra HD is a bit of a red herring as most devices and connections are not capable of getting it, and there’s not much content either. So really — the primary driver of price is number of screens — 1 for $9, 2 for $13 and 4 for $16.

This assumes the only difference between customers is the number of devices they want to watch content on at the same time. This is a misnomer. No one is watching 2 devices simultaneously— one with each eye?! So it’s really the number of users on an account — 1 user for $9, 2 users for $13 (nearly a 30% discount off list) or 4 users for $16 (a 45% discount from a single user account).

Consider some of the likely differences between consumers, and the variables by which they derive value:

- Number of Hours Watched

- Variety of Content Consumed (number of different shows and movies)

- ‘Binge Watchers’

- Demographics (geographic and individual)

- Devices, Connections and Locations Watched From

- Frequency and Length of Simultaneous Connections

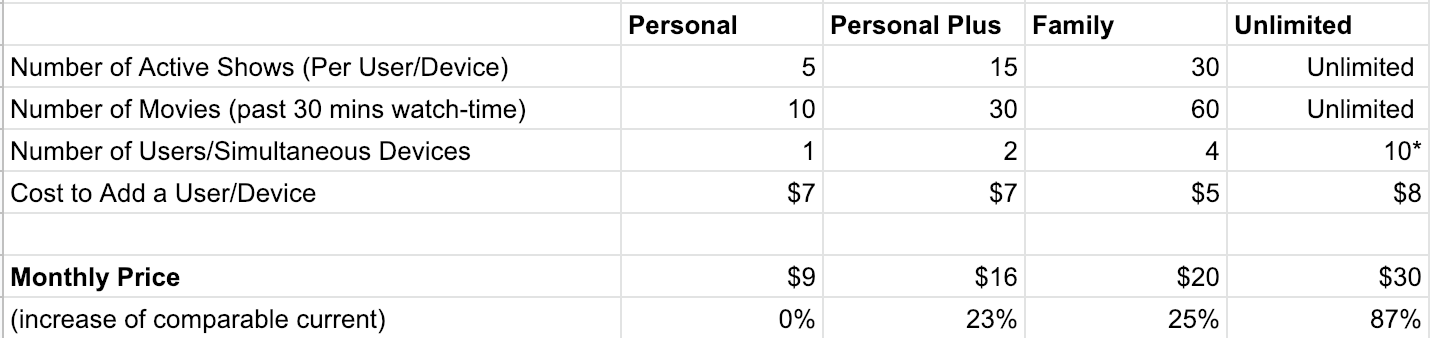

If you wanted to be aggressive, you could think about time of day, early access to new series and movies, premium content, subscriptions to different genres. But lets keep it simple for now — here’s a slightly more value-based pricing plan idea:

The base plan price hasn’t been changed— but that may be doable — so these increases are from what might already be a not optimized starting point.

On the Unlimited Plan — think about how many people have more than 1 user, watch Netflix multiple times a week, don’t ever want to think about usage limits and are not price sensitive to $30 a month for something they use regularly (and that has exclusive content they really want to see — Netflix has so many ‘must watch’ shows!)? Is it 10% of US subscribers? If so, a back-of-the-envelope calculation shows that’s likely over $1bn in 100% margin contributing revenue.

The real question is this — if Netflix changed its pricing model to be a little more complex and value-based — what is the level of change that can be sustained without materially reducing subscriber retention and addition? My guess is there’s at least enough leeway to reduce the need for debt to fund content.