When startup founders review a VC term sheet, they are mostly only interested in the pre-money valuation and the board composition. They assume the rest of the language is “standard” and they don’t want to ruffle any feathers with their new VC partner by “nickel and diming the details.” But these details do matter.

VCs are savvy and experienced negotiators, and all of the language included in the term sheet is there because it is important to them. In the vast majority of cases, every benefit and protection a VC gets in a term sheet comes with some sort of loss or sacrifice on the part of the founders – either in transferring some control away from the founders to the VC, shifting risk from the VC to the founders, or providing economic benefits to the VC and away from the founders. And you probably have more leverage to get better terms than you may think. We are in an era of record levels of capital flowing into the venture industry and more and more firms targeting seed stage companies. This competition makes it harder for VCs to dictate terms the way they used to.

But like any negotiating partner, a VC will likely be evaluating how savvy you appear to be in approaching a proposed term sheet when deciding how hard they are going to push on terms. If the VC sees you as naïve or green, they can easily take advantage of that in negotiating beneficial terms for themselves. So what really matters when you are negotiating a term sheet? As a founder, you want to come out of the financing with as much overall control of the company and flexibility in shaping the future of the company as possible and as much of a share in the future economic prosperity of the company as possible. With these principles in mind, let’s take a look at four specific issues in a term sheet that are often overlooked by founders and company counsel:

- What counts in pre-money capitalization

- The CEO common director

- Drag-along provisions

- Liquidation preference.

What counts in pre-money capitalization

When reviewing a term sheet, you’re often so focused on the pre-money valuation number itself that you can easily overlook the language that follows that number – which shares in the company count towards the pre-money capitalization. They’re not perfunctory words. And it actually matters how the pre-money share number is calculated. Not all VCs use the same formulations so you should be careful in parsing the language. The slightest variation can have a material effect on your percentage holding of the company.

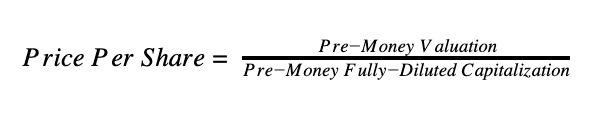

As you may know, the formula for the price-per-share paid by a VC in an equity round is this:

Basic math tells us that the denominator is just as important as the numerator in a formula like this. So, focusing on the pre-money valuation to the exclusion of the pre-money capitalization is a costly and unnecessary concession. The more shares that are included, the lower the per-share-price and the higher the percentage that the VC investor gets of the company.

You might think the way the pre-money capitalization is calculated is standard and non-negotiable, but that’s not true.

The following examples show how that pre-money fully-diluted capitalization number can vary. This definition of the purchase price only factors in the post-closing pool when calculating the fully-diluted share number:

Purchase Price: $XXXX per share based on the valuation divided by the pre-money fully diluted shares (including an increase in the option pool that results in post-financing available options equal to approximately 10% of the Company’s post-money full diluted capitalization.

This definition of the purchase price factors in the post-closing pool and any notes being converted but uses the post-money valuation to calculate the numbers:

Purchase Price: The per share purchase price shall be based upon the post-money fully-diluted valuation (assuming the full amount contemplated is raised, and which includes any note conversion shares, the unallocated pool and all other rights to acquire shares of the company’s capital stock.

Another way to say the same thing but using a pre-money valuation formulation instead is:

Purchase Price: The pre-money capitalization of the Company shall include (i) the company’s reserved but unissued, unpromised option pool, which shall constitute 10% of the post-money capitalization of the company on the basis of a fully subscribed round, (ii) any promised but unissued option grants, and (iii) shares issuable on conversion of the company’s outstanding SAFEs, convertible promissory notes or other convertible instruments.

That is not to say convertible securities should never be considered part of the pre-money capitalization number. As long as you have prepared a planning pro forma cap table and understood the implications of the various formulations above, you can make an informed decision on the terms presented by your VC. Just don’t gloss over the language and assume it’s non-negotiable.

The CEO common director

As I’m sure you’ve heard the horror stories of founders getting pushed out of their own companies, it is important for a founder to retain overall control of the board through the financing round. Your VC investor will likely get at least one seat on your board, if not more. And in addition to pushing for an independent director seat, they will insist that one of your common director seats go to the CEO. That language will sound innocuous to you because the founder is often the CEO in the early rounds. The provision in the term sheet will say something like this:

Board Composition: One director designated by the investor and two directors designated by the holders of a majority of the common shares, one of whom shall be the CEO.

But what happens when the founder is pressured into bringing a “professional CEO” or two founders have a falling out and the VC helps negotiate a truce by bringing in a new CEO? Suddenly, that new person will be required to have that common board seat. And if you’re still vesting your stock, you could risk losing your shares if terminated by the new board.

As long as the common shareholders have a majority of the shares in the cap table, there is a good basis to argue that the board should be controlled by the common shareholders, including the founders, even if the CEO is replaced in the future. The VC will argue that, for various business reasons, the CEO should have a board seat and that is why they are proposing that one common seat go to the then-serving CEO. However, in that case, everyone can be made happy by proposing something like the following:

Board Composition: One Series A director and two common directors. But if “founder” ceases to be CEO, then the board is expanded to five members, as follows: three common directors, one Series A director and one CEO director.

That’s just one of many ways to address the VC’s concerns and the founder’s concerns at the same time. The CEO is on the board, but the common shareholders still have a majority of board votes.

Drag-along provisions

As experienced founders can tell you, drag-along provisions, or provisions that require minority shareholders to vote their shares in favor of a majority-approved sale transaction, can be very important at an exit. The absence of such drag-along voting provisions in your corporate documents can lead to nightmare scenarios of hold-out shareholders that need to be bought out at the 11th hour. Unfortunately, many VCs will include a drag-along provision in the term sheet but only require approval of the preferred shareholders to trigger the drag-along. The common shareholders, or founders, should insist that the drag-along only be triggered if a majority of the common shareholders, voting as a separate class, approve the sale as well.

If the VCs agree to such a separate class vote, they will often insist that only the founders that are still with the company have the right to vote.

Drag-Along Provision: Holders of preferred stock and all current and future holders of common stock shall be required to enter into an agreement with the investors that provides that such stockholders will vote their shares in favor of a deemed liquidation event if approved by the (i) the holders of at least a majority of the common stock who are then providing services to the company, and (ii) holders of at least a majority of the outstanding shares of preferred stock, as a single class on an as-converted basis, subject to customary qualifications and limitations.

This cuts both ways. On one hand, it would mean that a founder that is pushed out would lose his or her ability to vote their own shares in connection with a merger. On the other hand, it would also prevent a disgruntled ex-founder from blocking a sale. You should think long and hard about the consequences of choosing the right drag-along provision for you.

Another variation in the drag-along provision that we would recommend all founders negotiate in their term sheets is a provision that allows the common shareholders to force the VC into the sale transaction if the preferred shareholders get at least “X” times their return. The language would read:

Drag-Along Provision: Holders of preferred stock and all current and future holders of common stock will be required to enter into an agreement that provides that such stockholders will vote their shares in favor of a deemed liquidation event or transaction in which 50% or more of the voting power of the company is transferred provided such transaction (i) is approved by the holders of a majority of the common stock, and (ii) yields the preferred stockholders a minimum 3X return on their investment.

This gives founders the flexibility to direct the future of the company if the investors can be guaranteed a certain minimum return. This version of the drag-along provision is not one that founders often ask for but it is one that the VCs sometimes agree to when prompted.

Liquidation preference

Most term sheets call for 1X, non-participating liquidation preference for preferred shareholders. This means the preferred shareholders have a choice in a liquidity event: 1) either get their money back; or 2)elect to convert into common stock and share in their pro rata percentage of sale proceeds. This is pretty standard and not something you are likely to be able to negotiate away.

But there may be negotiating room in the important details of how this plays out. In particular, there is the question as to whether preferred shareholders’ liquidation preference ends of serving to inoculate the VCs from any escrow or other holdback obligations. This is a detail most founders do not consider, but it can have huge economic impacts.

Usually a buyer will require a percentage of the proceeds to go into escrow to satisfy any indemnification obligations the company may have post-closing. Any funds left at the end of the escrow term (often 6 months to 2 years after closing of the transaction) get paid out to the shareholders. The VCs may ask that the burden of that escrow risk fall solely on the common shareholders and the preferred shareholders get 100% of their liquidation preference irrespective of the escrow holdback. The language would read something like this in the liquidation preference section:

Liquidation Preference: The Investors’ entitlement to their liquidation preference shall not be abrogated or diminished in the event part of the consideration is subject to escrow in connection with a deemed liquidation event.

This means if there is an escrow in an acquisition at a low purchase price and the liquidation preference is exercised, then a common shareholder could end up bearing all the risk of the escrow, rather than it being pro rata. When it comes to earn-outs or other contingent consideration, VCs will often object to sharing in the risk of future proceeds because those future payments are tenuous at best and rely on post-closing efforts by the founders typically.

They will only want to count the proceeds paid out at closing to determine their pro rata share or liquidation preference. However, escrow amounts and payments made out of escrow have nothing to do with post-closing actions of the company or its employees. It is a risk that exists at the time of closing. While it may be typical for VCs to not bear the risk of earn-out provisions or other contingent considerations in a sale transaction, for standard escrow holdback, all shareholders should bear the same risk, even if putting proceeds in escrow cuts into the preferred liquidation preference.

There are many other variations in a standard financing term sheet and it takes an experienced reader to recognize the ramifications of each formulation. Do not assume all of the language is standard. Run the term sheet by your counsel and ask them to educate you on each provision. And ask them to mark up the term sheet with a view to protecting the founders. While you may not ask for every point your counsel suggests, you will be making an informed decision if you’ve gone through the exercise.

[Editor’s note: This is part of our ongoing series of guest articles from industry experts, covering the hot topics that founders are wrestling with every day as they build their companies. If you have ideas for one, please email ec_editors@techcrunch.com]