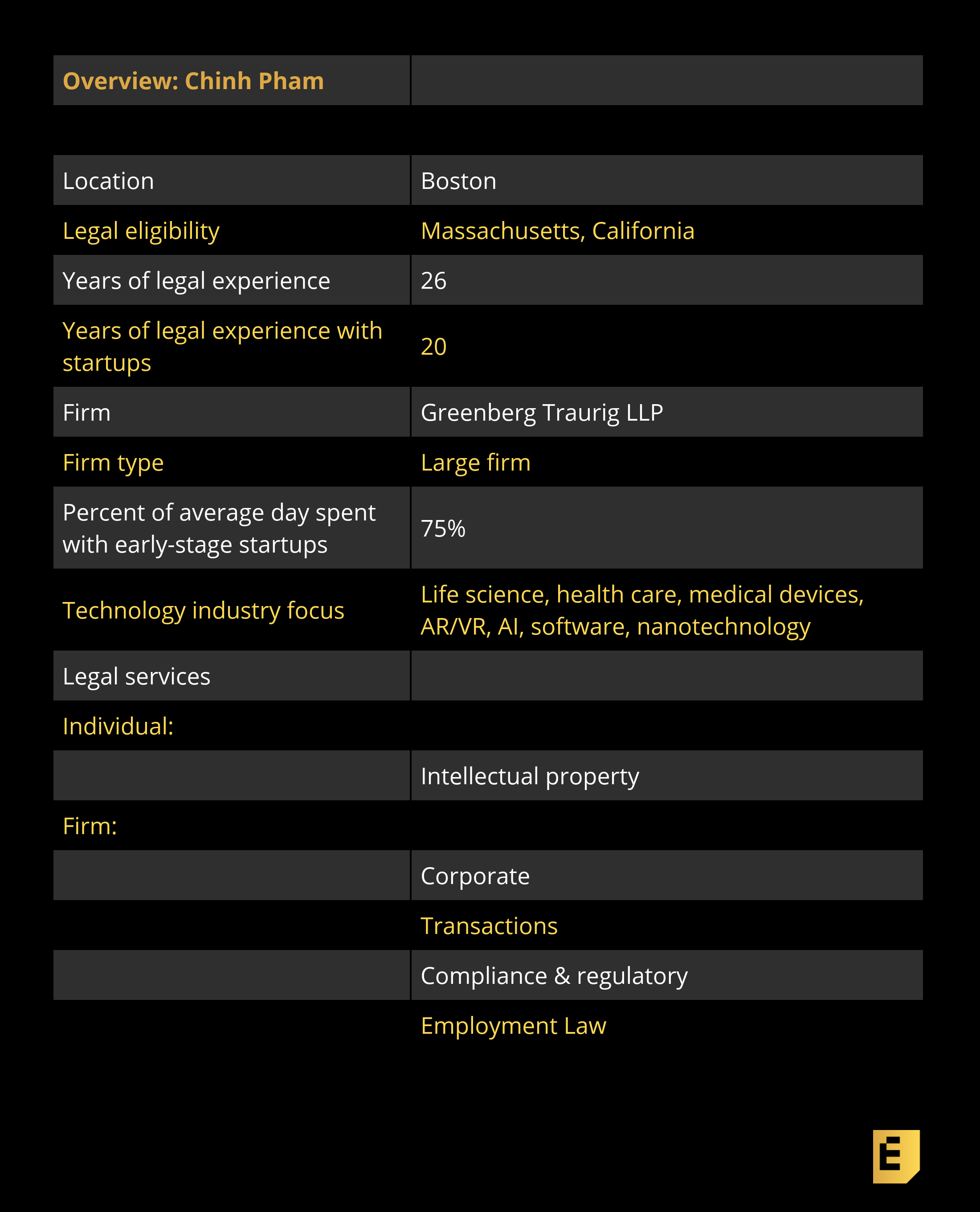

Chinh Pham got his first degree in genetics, but realized his real interest was the law as it applies to technology. Today, he combines his interests by working with a wide range of startups, including those in the life sciences, medical hardware and other industries where intellectual property defines a company from day one. As the chair of the emerging technology practice at international law firm Greenberg Traurig LLP, he and his team provide a range of services to companies from the ground floor up; he also spends significant time with commercialization programs at top universities.

On common startup mistakes:

“I’d say it is important to get all the founders in place and on the same page very early on. We’ve seen so many situations where there’s some internal turmoil before the company even gets off the ground, and then the whole venture falls apart. I typically suggest that each team member be responsible for specific tasks, because not everyone is good at everything.

“We are med-tech entrepreneurs who have created six companies over the past decade. Chinh has been with us since the beginning and has been one of the most significant contributors to the value we have created.” Lishan Aklog, MD, New York, NY, Chairman & CEO PAVmed Inc

“I also find that many student entrepreneurs are in the United States on an academic F1 visa. They may not realize that while they may found a startup, an F1 visa may not allow them to work or be employed by the startup. Therefore, consultation with an immigration attorney may be needed.”

On the importance of IP to many startups:

“I divide the world into wet, under which life sciences fall, and dry, under which everything else falls. Regardless of the type of client, I’ve found that most often IP is fairly critical for their success, because as they’re thinking about fundraising, they need a solid IP portfolio for investors to look at because most of these investors, as you know, aren’t going to put money into a company that really doesn’t have any innovation.”

Below, you’ll find founder recommendations, the full interview, and more details like their pricing and fee structures.

This article is part of our ongoing series covering the early-stage startup lawyers who founders love to work with, based on this survey and our own research. The survey is open indefinitely so please fill it out if you haven’t already. If you’re trying to navigate the early-stage legal landmines, be sure to check out our growing set of in-depth articles, like this checklist of what you need to get done on the corporate side in your first years as a company.

The Interview

Eric Eldon: First of all, how did you get into working with startups and within the wider world of the legal profession? I’d love to hear about your experiences working in Boston in particular as well.

Eric Eldon: First of all, how did you get into working with startups and within the wider world of the legal profession? I’d love to hear about your experiences working in Boston in particular as well.

Chinh Pham: My work with technology companies began while in law school in San Francisco back in the early 90s. As an intellectual property attorney, I’ve continued to work with technology companies, from startup phase to exit, throughout my entire career. Very early on in my legal career, an investor friend asked me about nanotechnology, which at that time, was a little-known but promising technology. I spent some time researching the nanotech industry and learning everything I could about the technology and its potential applications. Almost instantly, I was the nanotech expert at my firm and quickly became known as a nanotech specialist in the business world. That was an exciting time in my career, and I discovered that I loved the challenge and promise of emerging technologies, so I dedicated my practice to helping innovators develop, commercialize and protect their technologies.

Eldon: That sounds entrepreneurial.

Pham: I suppose you need to think entrepreneurially in order to represent entrepreneurs. Around that same time, I was involved with the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences over at Harvard, and a number of those professors knew my background in intellectual property and my work in the technology space. Over the years, I’ve formed a good relationship with these professors, and I enjoy helping them to determine the potential commercial implications of their research. I did that with Harvard, with UMass, and various other universities. That’s been going on for about two decades now.

When Harvard University launched its Innovation Lab, aka i-Lab, about a decade ago, some of the professors introduced me to the executive director at the i-Lab. Since then, I’ve been going over there on a weekly basis, advising these student entrepreneurs on their projects and the likelihood of success, and looking at the legal aspects of possible business opportunities for them.

After working with startups for so many years, I’ve realized that there are four main areas where the founders need assistance: corporate fundraising, IP, immigration, and labor employment. To address this need, we’ve created a team that we can connect with the student entrepreneurs at Harvard or other incubators to help address these questions, by holding office hours, giving a presentation, or networking with the innovators. One day, Northwestern University heard what we were doing at Harvard, and they asked if we could work with their new incubator, The Garage. Since then, I have been flying out to Northwestern University in Evanston pretty regularly to put on seminars and hold office hours.

Our approach to the academic incubators like Northwestern and Harvard is really to identify

universities that have strong R&D but also have a robust business program. I remember when the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences asked me to address the legal component of commercializing some of the research being done by their professors, and I suggested that they may want to team up with Harvard Business School, because that seemed like a logical gateway. Next thing I know, they have a program, and they invited me to go over and do a little presentation.

In addition to Harvard and Northwestern, we engage similarly with Northeastern University’s IDEA program, and a number of other high-profile universities as well.

I think this model works well for our Emerging Tech Group and is a benefit to both the schools and the startups coming out of major universities. By combining strong R&D with high-profile business programs, universities can compete more effectively for top students and faculty. Students nowadays are interested in doing startup work, and by creating this type of platform, it is appealing to all involved and everyone wins.

Eldon: Tell me more about your work with early stage companies and the services that you provide them and what percentage of your practice that is.

Pham: As chair of Greenberg Traurig’s Emerging Technologies Group, my approach is to have specific legal teams in place, whether those are IP, corporate formation, finance, immigration, tax or labor and employment lawyers. This multidisciplinary model enables us to help an early stage company with whatever the company may need as it progresses.

As for an example of my work with early-stage companies, I have a client in the medical device space that created a fund. The client’s goal is to determine a market need, then develop a product to meet that need, and subsequently spin out a company around the innovation created. The client team consisted of a number of doctors and one team member who served as CEO.

Essentially, the team would identify an area of need, whether it is surgical implants or some other medical product. They then prototype the product. If it works, the information is sent to me. Then we’ll create an entire IP portfolio based on their business objectives. Once some value is generated around the IP, they spin out a company around the IP, raise money, and eventually sell it off to a larger medical device company. We’ve spun out a number of different companies for this fund. The first one was really three years’ worth of work, and they sold it for a significant amount of money.

Eldon: Given that you’re oriented around industry sectors where IP is everything, and that you’re based in a life sciences hub, your view is probably pretty different from the consumer internet startups that usually make the headlines in Silicon Valley. When does IP matter for the clients you decide to work with?

Pham: Boston is certainly known for its life sciences market, but many of my clients are more on the software or materials side. I divide the world into wet, under which life sciences fall, and dry, under which everything else falls. Regardless of the type of client, I’ve found that most often IP is fairly critical for their success, because as they’re thinking about fundraising, they need a solid IP portfolio for investors to look at because most of these investors, as you know, aren’t going to put money into a company that really doesn’t have any innovation.

Eldon: What sort of advice do you give in general to entrepreneurs when they’re just starting out, assuming that they’re in an industry sector where IP is what decides everything? Let’s say you’re talking to a university spin-out. You do a lot of work there, and I know each university has its own policies in terms of of who owns what. So what sort of general advice do you give founders at that early stage of ‘You’re thinking about forming a company. Here’s what you need to have in mind’?

Pham: First, I’d say it is important to get all the founders in place and on the same page very early on. We’ve seen so many situations where there’s some internal turmoil before the company even gets off the ground, and then the whole venture falls apart. I typically suggest that each team member be responsible for specific tasks, because not everyone is good at everything.

Regarding companies that are spun out or licensing technology from universities, I think it’s worth reminding these companies that they need to think about who is going to own the innovation that’s going to be developed or arise from the licensed technology. If they are not careful with the terms of the license, the university may own all the IP, which is likely not good for a new company. In most cases, the new company should own any new innovation.

I also find that many student entrepreneurs are in the United States on an academic F1 Visa. They may not realize that while they may found a startup, an F1 Visa may not allow them to work or be employed by the startup. Therefore consultation with an immigration attorney may be needed.

Eldon: Can you tell me a little bit more about the disasters you’ve seen that you warn people against?

Pham: I’ll give you one great example involving a trademark issue. A startup company that was in the process of going public wanted to use a particular name but did not end up clearing the name beforehand. Long story short, when the public documents were being prepared, the issue of whether a search was done to see if the name was available came up, and we identified a few that may be problematic. We ended up working overtime to clear a new name so that the filing would not be further delayed. The company now is very diligent with clearing their trademarks.

Eldon: Wow. That delayed them going public?

Pham: It was a factor.

Eldon: Wow. Tell me a little bit more about operationally how you work, like what portion of your clients are early stage and how do you do billing for them?

Pham: I represent a wide range of tech companies, from large, multinational corporations to mid-sized companies to startups. Working with early stage companies requires some vetting on our part, based on a number of different criteria that we have developed. Depending on the situation, we can offer a flexible billing structure. At Greenberg Traurig, the billing structure has some flexibility, which is an important benefit to a startup organization. Based on a startup’s specific situation and legal needs, we can do what’s best for that client. Depending on the situation, we may be able to do a deferral, a reduced fee, a hybrid or a combination of other arrangements.

Eldon: Can you share any more about your prices, when you’ll decide to do deferred versus some sort of fee, and any more about the specific fee structure that’s normal for you?

Pham: Our billing structure is not uniform across the board, because we have 39 offices and more than 100 members in the Emerging Tech Practice Group. I will say the process is fairly flexible. It’s never black and white, but we aim to do what’s best for the startup to help them succeed.

Founder recommendations

“Chinh has always been available to answer questions as we developed our patent portfolio for our off road wheelchair, essential to growing and protecting our technology as we get our startup off the ground and battle for business against much larger incumbents. In addition to be transparent about the costs associated with the process, Chinh has opened GT’s Boston network such that we can learn about the community, not to mention effective IP advice. It’s been a positive relationship that has resulted in us not worrying about legal details and focus on getting more people with mobility challenges appropriate equipment to get outdoors and hiking.” — Ben Judge, Boston, MA, CTO, GRIT

“My company is a nanotech materials startup and Chinh not only provided guidance and expertise on intellectual property strategy but also brought his network influence to help us on strategic relationships.” — Mike Masterson, Boston, MA, founder and chairman, ALD NanoSolutions, Inc.

“Chinh and his firm helped my company, local technologies, create robust terms and conditions sheets, privacy policy sheets, and contractor sheets. They also helped us with our trademark and copyright applications. Further, they helped us form a C corp. Chinh also has helped numerous start-ups get patent applications approved, though he did not help my company do this.” — Collin Pham, San Francisco, CA Co-founder, Mistro

“Able to achieve broad claims on intellectual property applications and effectively navigate around prior art.” — A CTO of a medical device company in New York

“Their greatest contribution was taking us on in the first place. In the early days of the company, back when we just had pieces of paper which sketches and notes, we were looking for a firm that would listen to what we wanted, help us save money, and help us avoid obstacles. After consulting with 3 firms we settled on GT because they weren’t just trying to help us get a patent just to say we had one, but rather they helped us build an IP portfolio of value. Chinh also did something that no one else we had interviewed had done, which was try our prototype. This made me feel like he actually cared and believed in what we were trying to build. Since then, Chinh has helped us with in adapting our strategy to our changing financial positions and market conditions. We were able to strategically able to focus our IP strategy on key regions and even collapse some patent applications into each other cut costs while maintaining broad IP coverage.” Corey Mack, Los Angeles, CEO, LaFORGE Optical

“We are medtech entrepreneurs who have created 6 companies over the past decade. Chinh has been with us since the beginning and has been one of the most significant contributors to the value we have created. He is bright, knowledgeable and dogged in his pursuit of broad IP protection for his clients. He is a master claims writer — able to navigate examiner’s responses and cited prior art without narrowing scope of claims, which is what many IP attorneys do. His expertise extends beyond our niche of medical technology and includes specific expertise in nanotechnology for which he has received national awards.” — Lishan Aklog, MD, New York, New York, CEO and chairman of PAVmed Inc

“Chinh discusses solutions in ‘human being’ language even when dealing with IP and start-up labor laws. He has proven himself invaluable to my clients as they navigate the world of start-ups, to buy-outs, to public offerings.”— J. Timothy Delaney, Managing Director of Investment Strategy, Lowell Blake & Associates, Inc.