Squad could be the next teen sensation because it makes it easy to do nothing… together. Spending time with friends in the modern age often means just being on your phones next to each other, occasionally showing off something funny you found. Squad lets you do this even while apart, and that way of punctuating video chat might make it the teen girl “third place” like Fortnite is for adolescent boys.

With Squad, you fire up a video chat with up to six people, but at any time you can screenshare what you’re seeing on your phone instead of showing your face. You can browse memes together, trash talk about DMs or private profiles, brainstorm a status update, co-work on a project or get consensus on your Tinder swipe. It’s deceptively simple, but remarkably alluring. And it couldn’t have happened until now.

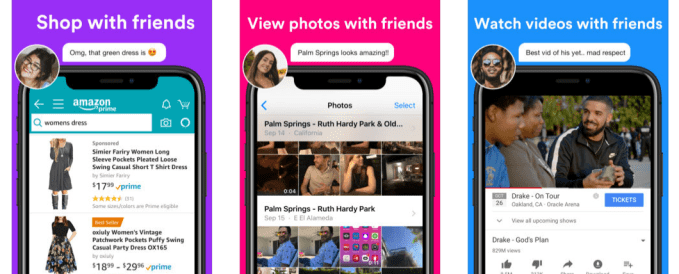

How Squad screensharing looks

Squad takes advantage of Apple’s ReplayKit for screensharing. While it was announced in 2015, it wasn’t until June 2018’s iOS 12 that ReplayKit became stable and easy enough to be built into a consumer app for teens. Meanwhile, plus-size screens and speedy LTE and upcoming 5G networks make screensharing watchable. And with Instagram aging and Snapchat shrinking, there’s demand for a more intimately connected social network.

Squad only launched its app last week, but droves of Facebook and Snap employees have signed up to spy on and likely copy the startup, co-founder and CEO Esther Crawford tells me. Screensharing would fit well in group video chat startup Houseparty too. To fuel its head start, Squad has the $2.2 million it raised before it pivoted away from Molly, the team’s previous App where people can make FAQs about themselves. That cash came from betaworks, Y Combinator, BBG Ventures, Basis Set Ventures, Jesse Draper, Gary Vaynerchuk, Niv Dror, and [Disclosure: former TechCrunch editor] Alexia Bonatsos’ Dream Machine. Next, Squad wants to let people tune in to screenshares via URL to unlock a new era of Live broadcasting, and equip other apps with the capability through a Squad SDK.

“People under 24 do video chat way different than people 25 and above” says Crawford. Adding screensharing is “an excuse for hanging out.”

Serious ideas are preludes to toys

Screensharing has long been common in enterprise communication apps like Webex, Zoom and Slack. I even called a collaborative browsing and desktop screensharing app my favorite project from Facebook’s 2011 college hackathon. But we don’t just use our screens for work any more. Teens and young adults live on the digital plane, navigating complex webs of friendships, entertainment and academia through their phones. Squad makes those experiences social — including the “social” networks we often scroll through in isolation. Charles and Ray Eames said “Toys are preludes to serious ideas,” but this time, it is happening in reverse.

Squad co-founders from left: Ethan Sutin, Esther Crawford

“The idea came from a combination of things — a pain we were experiencing as a team,” Crawford recalls. My development team is constantly sending each other screenshots and screen recordings. It seemed ridiculous that I can’t just show you what’s on my screen. It was a business use case internally.” But then came the wisdom of a 13-year-old. “My daughter over the summer was bugging me. ‘Why can’t I just show what’s on my screen with my friends?’ I said I think it’s not technically possible.” That’s when Crawford discovered advances in ReplayKit meant it suddenly was possible.

Crawford had already seen this cycle of tool to toy before, as she was an early YouTuber. Back in the mid-2000s, people thought of YouTube as a place to host videos about eBay listings, professional presentations or dating profile supplements. “They couldn’t imagine that if you let people just reliably and easily upload video content, there’d be all these creative enterprises.”

Use cases for Squad

After stints in product marketing at Coach.com and Stride Labs, she built Estherbot — a chatbot version of herself that let people learn about her. Indeed, 50,000 people ended up trying it, convincing her people needed new ways to reveal themselves to friends. She met Ethan Sutin through the project and together they co-founded FAQ app Molly before it fizzled out and was shut down. “Molly wasn’t working; it had high initial engagement sessions, but then they would drop off. Maybe it’s not the right time for the augmented version of you,” noted Crawford.

Crawford and Sutin pivoted Molly into Squad to keep exploring new formats for vulnerability. “What excited Ethan and I was this mission to help people feel less lonely.”

Alone, together

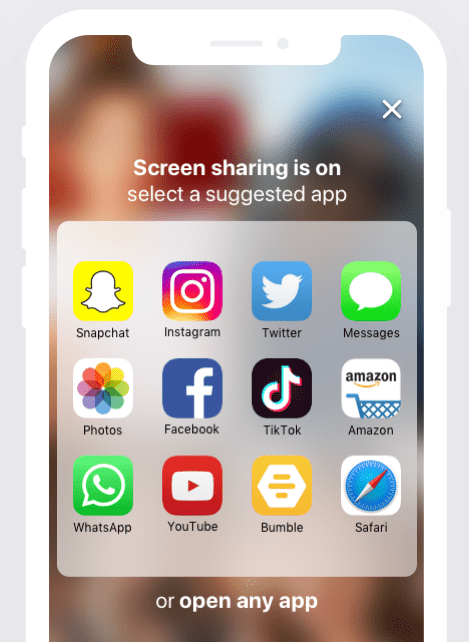

Squad recommends apps to screenshare

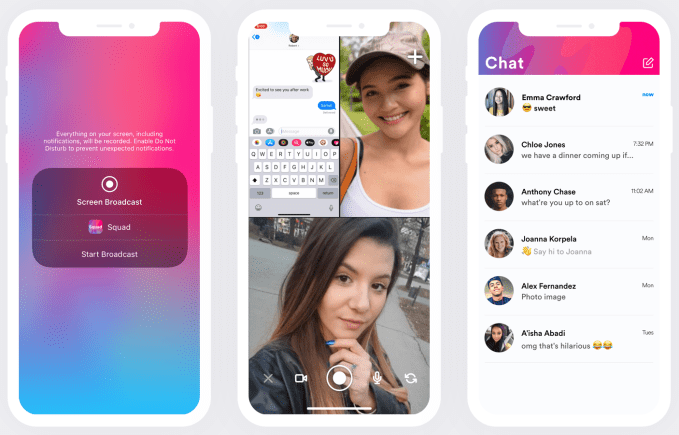

Squad worked, thanks to a slick way to activate screensharing. The app launches to the selfie camera similar to Snapchat, but with a + button for inviting friends to a video call. Tap the screenshare button at the bottom, select Squad and start the broadcast. To guide users toward the best screensharing experiences, a menu of apps emerges encouraging users to open Instagram, TikTok, Bumble, their camera roll and others.

People can bounce back and forth between screensharing and video chat, and tap a friend’s window to view it full-screen. And when they want another friend to see what they’re seeing, Squad goes viral. One concern is that Squad breaks privacy controls. You could have friends show you someone’s Instagram profile you’re blocked by or aren’t allowed to see. But the same goes for hanging out in person, and this is one reason Squad doesn’t let you download videos of your chats and is considering screenshot warnings.

What’s so special about Squad is that it lacks the intensity of traditional video chat, where you constantly feel pressured to perform. You can fire up a chat room, and then go back to phoning as you please with your screen displayed instead of your blank face (though the Android version in beta offers picture-in-picture so you can show your mug and the screen).

“There’s no picture-in-picture on iOS, but younger users don’t even really care. I can point it at the bed and you can tell me when there’s something to look at,” Crawford tells me. A few people, alone in their houses, video chatting without looking at each other, still feel a sense of togetherness.

The future of Squad could grant that feeling to a massive audience of a celebrity or influencer. The startup is working on shareable URLs that creators could post on other social networks like Twitter or Facebook that their fans could click to watch. Tagging along as Kylie Jenner or Ninja play around on their phone could bring people closer to their heroes while serving as a massive growth opportunity for Squad. Similarly, colonizing other apps with an SDK for screensharing could allow Squad to recruit their users.

Squad makes starting a screenshare easy

The startup will face stiff technical challenges. Lag or low video quality destroy the feeling of delight it delivers, Crawford admits, so the team is focused on making sure the app works well even in rural areas like middle America where many early users live. But the real test will be whether it can build a new social graph upon the screensharing idea if already popular apps build competing features. Gaming tools like Discord and Twitch already offer web screensharing, and I suggested Facebook should bring the feature to Messenger when in late-2017 it launched in its Workplace office collaboration app.

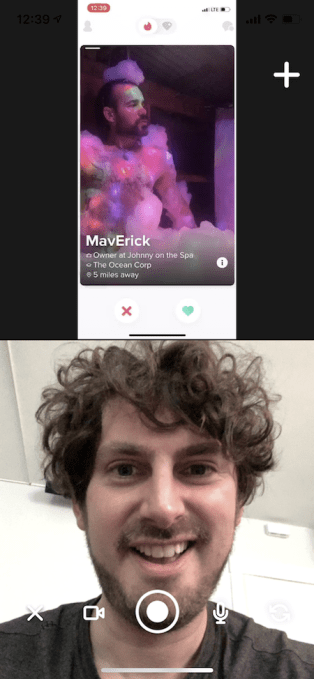

Helping a friend choose when to swipe right on Tinder via Squad

In June I wrote that Instagram and Snapchat would try to steal the voice-activated visual effects at the center of an app called Panda. Snapchat started testing those just two months later. Instagram’s whole Stories feature was cloned from Snapchat, and it also cribbed Q&A Stories from Polly. Overshadowed, Panda and Polly have faded from the spotlight. With Facebook and Snap already sniffing around Squad, it’s quite possible they’ll try to copy it. Squad will have to hope first-mover advantage and focus can defeat a screensharing feature bolted on to apps with hundreds of millions or even billions of users.

But regardless of who delivers this next phase of sharing, it’s coming. “Everyone knows that the content flooding our feeds is a filtered version of reality. The real and interesting stuff goes down in DMs because people are more authentic when they’re 1:1 or in small group conversations,” Crawford wrote.

Perhaps there’s no better antidote to the poison of social media success theater that revealing that beyond the Instagram highlights, we’re often just playing around on our phones. Squad might not be glamorous, but it’s authentic and a lot more fun.