In a world where nothing can be trusted and fake news abounds, ICO and crypto teams are further muddying the waters by trying – and often failing – to pay for posts. While bribes for blogs is nothing new, sadly the current crop of ICO creators and crypto projects are particularly interested in scaling fast and many ICO CEOs are far happier with scammy multi-level marketing tricks than real media relations.

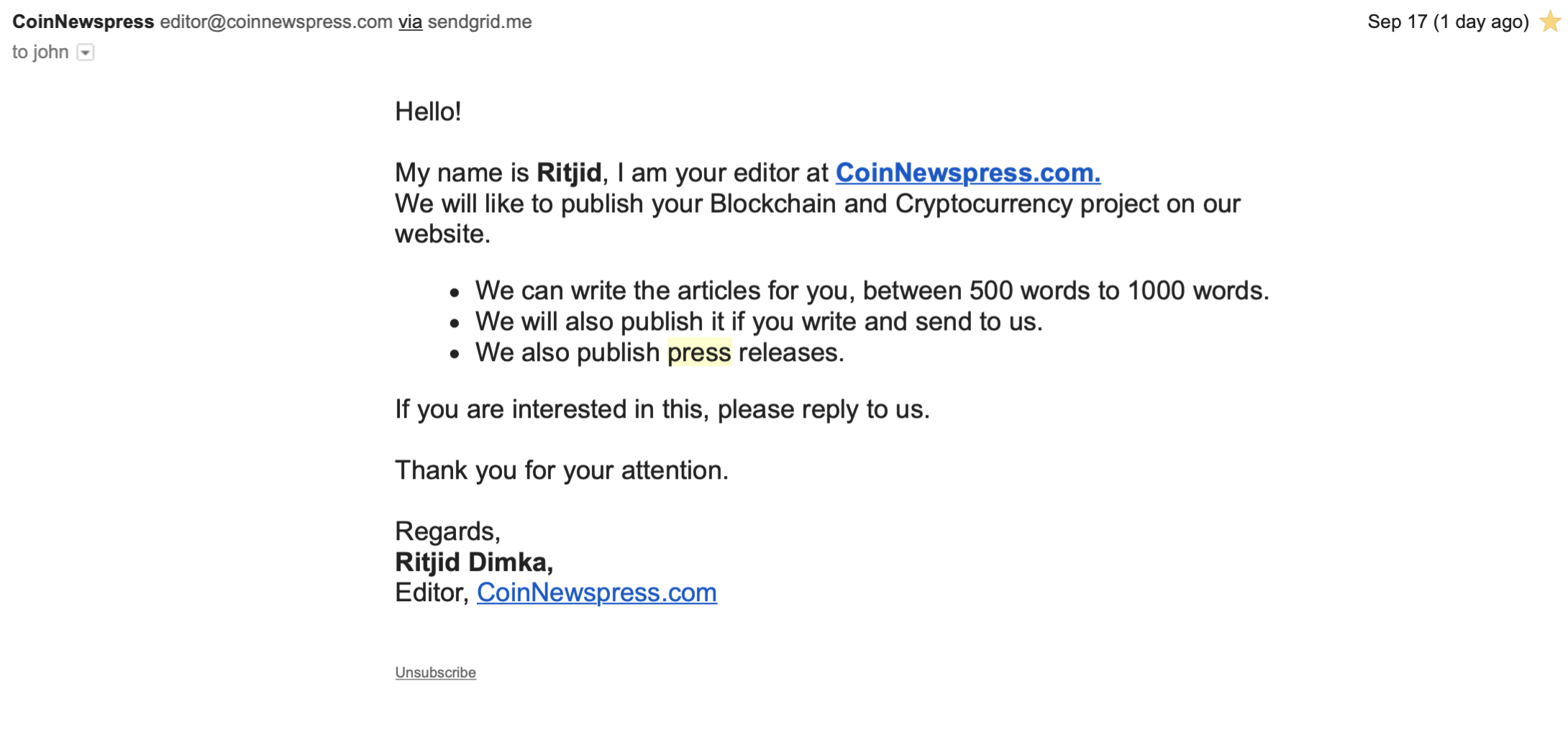

The worst part of this spammy, scammy ecosystem is the service providers. A new group of media organizations are appearing where pay-to-post is the norm rather than the rare exception. I’ve been looking at these groups for a while now and recently found a few egregious examples.

But first some background.

Oh yeah, Mr. Smart Guy? How do I get press?

Say you’re trying to publicize a startup. You’ve emailed all the big names in the industry and the emails have gone unanswered. Your product is about to flounder on the market without users and you can’t get any because, in perfect chicken-or-egg fashion, you can’t get funding without users and you can’t get users without funding. So isn’t it a good idea to pay a few dollars for a little press?

No.

And isn’t most PR just pay-for-post anyway?

No.

PR people are consummate networkers and are paid to reach out to media on your behalf and their particular set of skills, honed over long careers, are dedicated to breaking down the forcefield between the journalist and the outside world. They are your surrogate hustlers, dedicated to getting you more exposure. A good PR person is worth their weight in gold. They can call up a popular journalist and make a simple pitch: “This cool new thing is happening. Can I put you in touch?”

If a journalist’s mission is to afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted, a good PR person makes the comfortable look slightly afflicted in order to give the journalist a better story. Also, like velociraptors, they are tenacious and will follow up multiple times on your behalf.

A bad PR person, on the other hand, will cold-call hundreds of journalists and read a script that is half the length of Moby Dick. They produce little more than spam and their efforts begin and end with pressing the “Send” button. It’s also interesting to note that many bad PR people, of late, have found new life as ICO specialists.

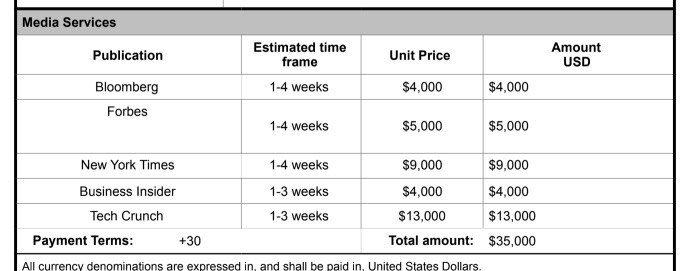

Now meet the pay-for-post hucksters. As I wrote before, there is now a subset of the PR world that offers to get your press release or story on the top of various websites for the low, low price of between $500 and $13,000. For example, one set of hucksters created a small business selling posts on Harvard.edu by creating garbage WordPress blogs and posting press releases to increase SEO coverage. Further, I received a document that outlined the prices for placement in various blogs including this one. While it is impossible to buy a post on TechCrunch this way, it doesn’t stop many from trying.

What’s the difference between that price list and the job a PR person will do for you? The difference is trust. A pay-for-post huckster is dependent on convincing poorly paid freelance writers to add links and other dross to their posts in order to get a “placement.” I get requests like this almost every day and almost all the journalists I talked to reported the same.

Some entrepreneurs are savvy enough to avoid these scams. Even more aren’t.

“I’ve never paid since I think it’s almost always a waste of money but I’ve been offered this type of coverage many times,” said Rick Ramos, of HealthJoy.com. “The last offer was for Kathy Ireland’s Worldwide Business… A TV show that I’ve never heard of in my life. I’ve also been approached by niche publications like InsuranceOutlook and HealthCareTechOutlook that want $3,000 for a ‘reprint branding package.’ A quick Alexa.com search shows their rank as 1,725,207 and 1,054,501 globally. I think I get pitched at least every six months for one of these types of packages.

Unfortunately, many of these organizations hide their request for payment until the last minute. That said, how do you know when it’s someone selling pay-for-play vs. a real editor? It’s usually obvious.

“It’s usually pretty easy to sniff out based on their email blast. It’s pretty untargeted with no reference to what your company does or how it related to a story. Some people are up front about the payment but others want a ’15 min call to discuss.’ A quick LinkedIn search always shows them as a sales person versus a reporter or editor,” said Ramos.

It’s getting worse

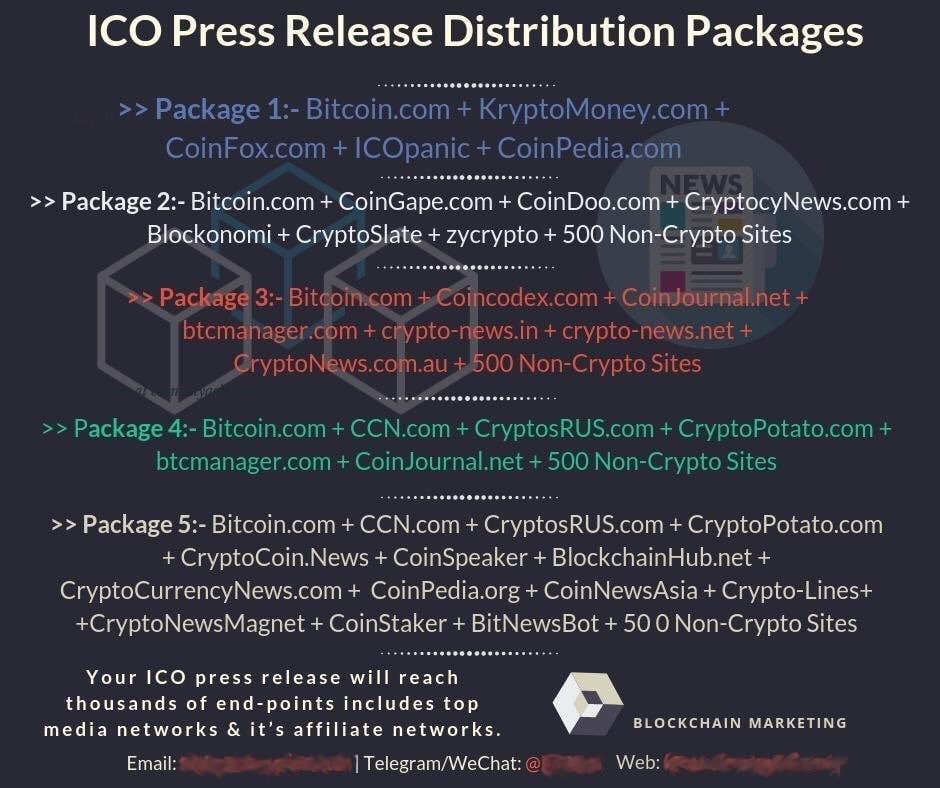

This is a document I received from a company attempting an ICO. This sort of menu was quite uncommon until fairly recently when the “on-demand” economy melded with PR scammers. The completeness of the document is unique – you could feasibly plan your own PR efforts just by reaching out to journalists who work at all of these places. But you’ll also note that each spot has its own price, often in the low hundreds of dollars, which means that those spots are mostly pay-for-play anyway.

ICOLists by on Scribd

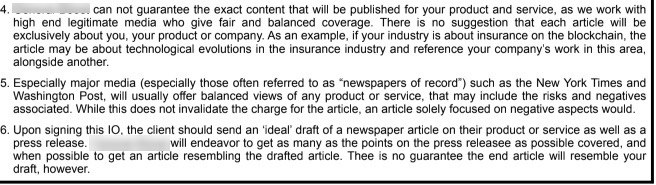

No PR company can promise coverage. In fact, many pay-for-play folks mention this in their communications, hiding it in plain sight. This snippet of text appeared in a contract for work from one of the pay-for-play providers. In short, you’re paying for something they cannot guarantee to get. Interestingly, the PR company below calls their product an IO – an insertion order – which is language used in ad sales. Further, they take great pains in explaining that it is almost impossible to achieve what they promise.

None of the pay-for-post folks I mentioned here would respond to my requests for comment.

Counter-point: Journalists are also at fault

Journalists should never expect money for coverage.

Yet many do.

“Lately I have worked on a number of blockchain technology pieces and I have encountered a wide variety of these asks,” said Brittany Whitmore, CEO at Exvera Communications. “A lot of the new, smaller blockchain-focused outlets seem to do a lot of pay-to-play, likely trying to capitalize on the ICO gold rush. The strangest request that I received was that the outlet would do a an article about the news for free but only if we paid them over $1,000 to promote the article with ads. I did not proceed.”

In one very detailed article on The Outline, Jon Christian explored this world and found that many writers received small sums for a single brand mention in a story, a sort of SEO flogging that rarely helps. He wrote:

An unpaid contributor to the Huffington Post, also speaking on condition of anonymity because, in his words, “I would be pretty fucked if my name got out there,” said that he has included sponsored references to brands in his articles for years, in articles on the Huffington Post and other sites, on behalf of six separate agencies. Some agencies pay him directly, he said, in amounts that can be as small as $50 or $175, but others pay him through an employee’s personal PayPal account in order to obfuscate the source of the funds. In a statement, Huffington Post said “Using the HuffPost Contributors Network to self-publish paid content violates our terms of use. Anyone we discover to be engaging in such abuse has their post removed from the site and is banned from future publication.”

The Huffington Post writer also described specific brands he’d written about on behalf of one of the agencies, which ranged from a popular ride-hailing app, to a publicly-traded site for booking flights and hotels, to a large American cell phone service provider.

“This is a classic example of payola,” he said of the brand mentions, invoking a term that’s been used to describe radio DJs who accept payments from record companies in order to play certain artists on the air.

Further, many influencers – folks who sell their Internet fame to the highest bidder – masquerade as journalists, asking for outrageous sums to flog an ICO on their YouTube channel or Instagram page. Pay-for-play services can also put out organic content like this in hopes of appearing in the news.

The rule of thumb? Paid posts and native advertising are not journalism. Ultimately, journalists who charge for coverage are marketers. No one at any reputable news organization will ask for cash but, sadly, there are a number of disreputable news organizations making the rounds.

ICO spamming/Don’t do it

All this still doesn’t answer the question: Should you pay-to-post?

“The short answer is no,” said Kevin Bourke of BourkePR. “I get asked all the time, and in fact, turned down another request just today. And I advise my clients to decline these offers as well.”

Pay-for-post disrupts journalism in a way that should be familiar and desirable to any modern-day entrepreneur. Middlemen are being knocked out everywhere and brands are approaching consumers from every angle including native ads in Instagram and Twitter. But the value of coverage – real coverage – from a journalists perspective is the opportunity to explain complex ideas to a ready audience. While posting a picture of a blockchain on Facebook and hoping for clicks is one strategy, explaining your views, opinions, and insights is far more important even if you approach it from a mercenary position.

“When you start paying for placement, you remove objectivity and credibility, and in my opinion, this is the reason you look for coverage of your company/products in the first place. That’s what influences readers/viewers. But I understand the temptation for startups. You come to believe that ‘all visibility is good visibility.’ I just can’t agree with that,” said Bourke. “I see the trend toward paid placements (now called sponsored content), paid awards and I can’t stand it – especially with the trade show awards in high tech. They’ve completely devalued the Best of Show awards in so many cases. Typically, only the big companies with budgets can afford them, so many of the smaller guys with no money but amazing products get left out. I understand that the publishing industry needs to figure out new revenue streams – these are very difficult times for them. But they need to figure out smarter business models and maintain the integrity of editorialized content, built on the opinions and perspectives of journalists and influencers.”