Descartes Labs, a New Mexico-based geospatial analytics startup, today announced that its platform is now out of beta. The well-funded company already allowed businesses to analyze satellite imagery it pulls in from NASA and ESA and build predictive models based on this data, but starting today, it is adding weather data to its library, as well as commercial high-resolution imagery thanks to a new partnership with Airbus’ OneAtlas project.

As Descartes Labs co-founder Mark Johnson, who you may remember from Zite, told me, the team now regularly pulls in 100 terabytes of new data every day. The company’s clients then use this data to predict the growth of crops, for example. And while Descartes Labs can’t disclose most of its clients, Johnson told me that Cargill and teams at Los Alamos National Labs are among its users.

While anybody could theoretically access the same data and spin up thousands of compute nodes to analyze it and build models, the value of a service like this is very much about abstracting all of that work away and letting developers and analysts focus on what they do best.

“If you look at the early beta customers of the system, typically it’s a company that has some kind of geospatial expertise,” Johnson told me. “Oftentimes, they’re collecting data of their own and their primary challenge is that the folks on their team who ought to be spending all their time doing science on the data sets — the majority of their time, sometimes 80 plus percent of their time — they are collecting the data, cleaning the data, getting the data analysis ready. So only a small percentage of their work time is spent on analysis.”

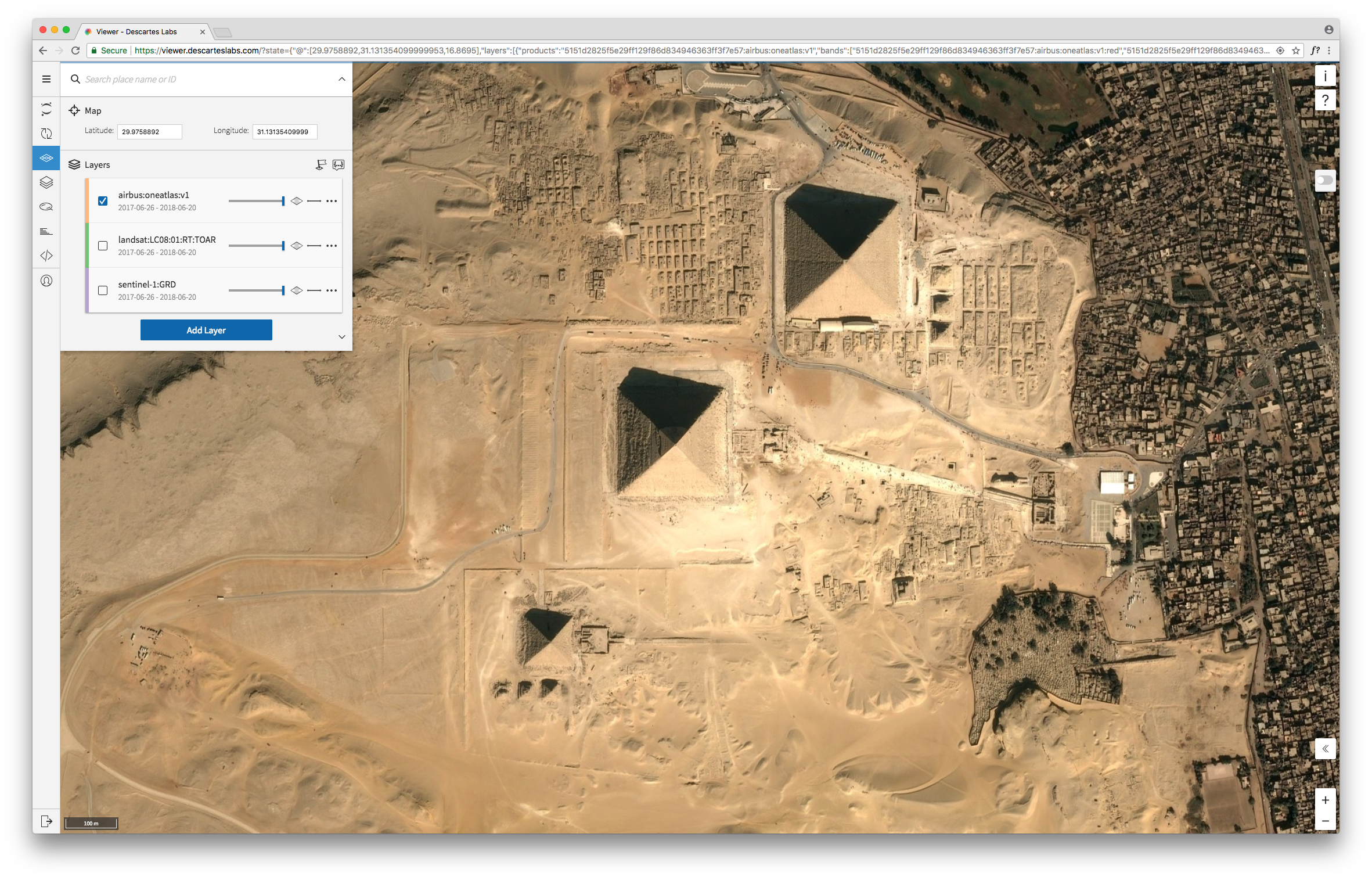

So far, Descartes Labs’ infrastructure, which mostly runs on the Google Cloud Platform, has processed more than 11 petabytes of compressed data. Thanks to the partnership with Airbus, it’s now also getting very high-resolution data for its users. While some of the free data from the Landsat satellites, for example, have a resolution of 30m per pixel, the Airbus data comes in at 1.5m per pixel across the entire world and 50cm per pixel over 2,600 cities. Add NOAA’s global weather data to this, and it’s easy to imagine what kind of models developers could build based on all of this information.

Many users, Johnson tells me, also bring their own data to the service to build better models.

While Descartes Labs’ early focus was on developers, it’s worth noting that the team has now also built a viewer that allows any user (who pays for the service) to work with the base map and add layers of additional information on top.

Johnson tells me that the team plans to add more data sets over time, though the focus of the service will always remain on spatial data.