Editor’s note: This post originally appeared on TechNode, an editorial partner of TechCrunch based in China.

When Emily Zhang was interning with a peer-to-peer (P2P) lending firm in the Summer of 2016, her main task was to carry out research on other P2P lending firms. She found the rates of return tempting and some underlying assets reliable, so she decided to invest in the market herself. Until now, none of her investments have matured, but she worries about whether she can actually withdraw her profits, much less get back the principal.

Even so, Zhang considers herself lucky that the companies that sold her the assets are still in business while many other P2P companies have collapsed, leaving their investors in despair.

Stories have been circulating across Chinese social networks about desperate investors who have lost their life savings. Zhang Xue, for instance, a 47-year old single mother with a 13-year-old son, was reported to have lost the 3.8 million RMB her husband left her with when he died of a heart attack. “I am totally desperate. 3.8 million RMB. It’s finished, all finished,”” she told local media.

Some of those affected protested in front of police stations and chanted the Chinese national anthem, March of the Volunteers, in an effort to pressure authorities. Others organized online investor rights groups, making a collective effort to get the money back. Together, the protesters made headlines in domestic media and sparked intense online debates on who is responsible for the losses and where the industry is heading.

P2P lending, or online lending, is generally considered as a method of debt financing that directly connects borrowers, whether they are individuals or companies, with lenders. The world’s first online lending platform, Zopa, was founded in the UK in 2005. China’s online lending industry has seen rapid growth since 2007 without significant regulation.

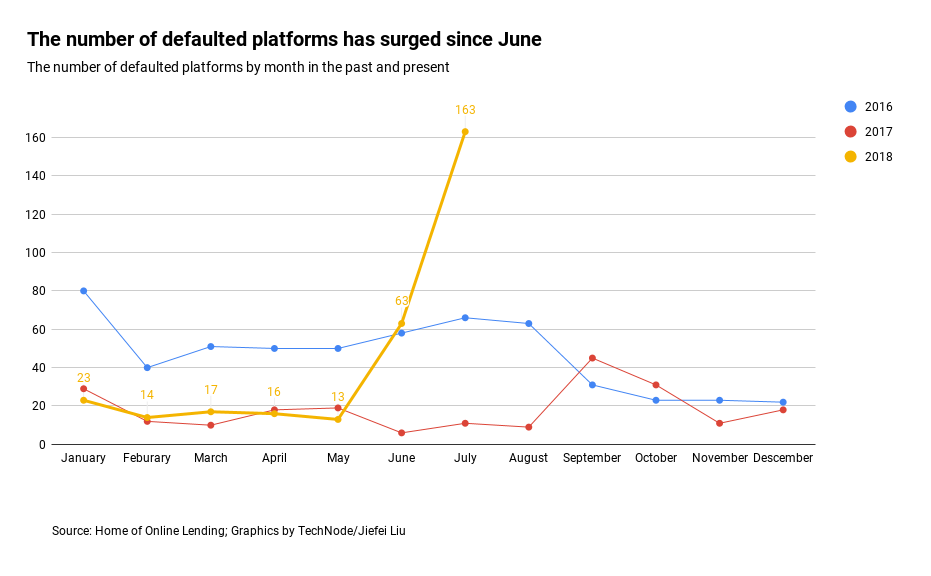

Default rates have been soaring since June. In May, only 10 platforms were considered in trouble. But by June, that number had increased to 63. By the end of July, 163 platforms were on the concern list. The Home of Online Lending (网贷之家), a platform that compiles the data, defines ‘troubled’ as companies that have difficulty paying off investors, have been investigated by national economic crime investigation department, or whose owners have run away with investors’ money.

One of the key factors contributing to the sudden surge is the national P2P rectification campaign that was supposed to have been finished by June. “The due date of rectification has passed, but many P2P platforms have not met the requirements. Strict regulations have propelled a break-out of the compliance issues,” Shen Wei, Dean and Professor of Law at Shangdong University Law School, told TechNode.

In late 2017, the platforms were asked to register with local authorities by June 2018, according to China Banking Regulatory Commission, which has now merged with China’s insurance regulator to become China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission.

Shen said the main purpose of the regulations is to restrict P2P lending platforms to be information intermediaries only, matching borrowers and investors. Under such regulations, the platforms are not allowed to pool funds from investors or grant loans to any client or provide any credit services, which most of the platforms were doing when they first started.

The rise of P2P lending in China

China’s first online lending platform, PPDAI Group (拍拍货), launched in 2007 and went public on the New York Stock Exchange in late 2017. The industry has gone through rapid growth since then. In January 2016, there were 3,383 platforms in business with combined monthly transactions reaching 130 billion RMB, according to Home of Online Lending.

In a recent research paper, Robin Hui Huang, professor of law at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, attributed the increase of P2P in China to three factors: a high 56 percent rate of internet penetration by 2018, a large supply of available funds from investors, and financial demands of small-to-medium-sized companies that cannot be satisfied by the existing banking system.

P2P lending is a tempting and easy investment option because the loans usually promise 8-12 percent interest rates, according to Home of Online Lending, of which many mature within a year, much higher than the 2.75 percent rate for three-year fixed deposits found at most banks.

P2P lending is also friendlier to smaller businesses since major banks in China generally prefer state-owned enterprises or large companies. Huang cited a joint 2016 report by the Development Bank of Singapore and Ernst & Young, that only 20-25 percent of bank loans went to small to medium-size enterprises, even though they accounted for 60 percent of China’s gross domestic product.

China’s financial system is still dominated by banks, especially the established ‘Big Four’ — the Bank of China, China Construction Bank, the Agricultural Bank of China, and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China. Ryan Roberts, a research analyst at MCM Partners, told TechNode that about 70 percent of the banks’ loans are commercial loans, with just 30 percent for individuals.

Unresolved regulations

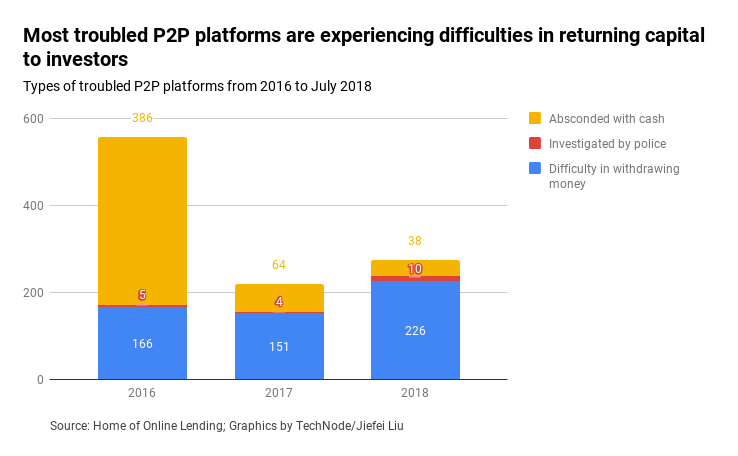

Before the government first signaled regulations in 2016, the P2P lending industry aggressively expanded. Compared with the current defaulting scandals, the situation back then wasn’t any better.

By the end of 2015, there were 1,031 total troubled platforms out of 3,448 platforms still in operation. So, on average, one out of four was problematic. Chinese media reported on a number of Ponzi scheme stories concerning dubious platforms that tempted would-be investors with fat bonuses for referring family and friends, too.

Despite the fact that there was no established regulatory framework, the government was watching. Since mid-2015, a series of announcements set the stage for China’s first regulatory instrument for online lending in August 2016. Called Interim Measures on Administration of Business Activities of Online Lending Information Intermediaries, violations of its articles can lead to administrative or even criminal penalties.

The interim measures set the business scope of the platforms to be mere information intermediaries. It also asked all platforms to set up custody accounts with commercial banks for investor and borrower funds held by the platforms in order to reduce the risks that platform owners abscond with funds. The measures require online lending platforms to register with their local financial regulatory authority.

Later, a specific timeline was set for the implementation. Provincial government agencies were told to complete general investigations into local P2P platforms by July 2016 and formulate regulatory policies based on regional conditions. Overall rectification and registration should have been completed by June 2018, the latest.

It’s August now and, obviously, the work still isn’t finished. Huang said the measures, in general, have covered all the factors of the industry that should be regulated, but when it came to implementation, all we really saw was a delay.

“It’s good that the measures are carried out locally, which means that local government can develop policies in line with local conditions,” Huang explained to us. However, in order to attract more capital locally, local authorities have engaged in a race to the bottom, competing with one and another to have the loosest regulations, and therefore, have been hesitant to finalize them.

Moreover, the general public has a different understanding of the registration process. “Registering with local authorities doesn’t mean that local governments have recognized or will guarantee the legitimacy and quality of platforms. However, in reality, the public seems to perceive registration as official assurance,” Huang said. This has lead to very cautious approaches from government agencies towards the whole registration project since they don’t intend to be held responsible for the fallout or future wrongdoings of the P2P firms.

The concern is quite reasonable. Huoq.com—a P2P lending platform launched in December 2016 and backed by state-owned enterprises—announced on July 11, 2018, that it went into liquidation. The platform is owned by Dingxi Zhuoyue Online Lending Information Intermediary. One-third of Dingxi is owned by Xinjiang Tianfu Lanyu Optoelectronics Technology while Tianfu Lanyu itself is partly owned by a state-owned company in Xinjiang. On July 10, however, owners of the platform disappeared. Neither the company nor investors were able to locate them.

Their still-functioning official site doesn’t show the slightest sign of liquidation, displaying various certificates and recognition from government agencies and industry associations. A banner at the bottom of their mobile app icon still says “Central enterprises are our majority shareholders.”

The unresolved regulations are also affecting P2P lending companies listed overseas. Shares of PPDAI plummeted to $4.77 as of July 30 from $13.08 when it was first traded in late 2017. The stock price of Yirendai (宜人贷), the first Chinese online lending company to go public overseas, dropped to $19.33 compared with $38.26 the same period last year.

That the shares of these companies don’t trade well indicates that investors are skeptical towards the business, said Roberts. With the ongoing regulations, it’s still possible that regulators can outlaw and ban their businesses, he explained. Some borrowers even take advantage of the unsettled regulation and stop paying back their loans, in the hopes that the platform they have borrowed from would fail, Roberts added.

Buyer beware

In June 2018, 17.8 billion RMB worth of transactions took place on China’s P2P lending platforms and outstanding loan balance reached 1.3 trillion RMB. The number looks insignificant if compared with 1.8 trillion RMB in net new bank loans in June alone.

However, they have made quite a splash. Victims of the troubled online lending platforms gathered in Hangzhou in early July, filling two of the largest local sports stadiums, which the local government had set up as temporary complaint centers.

“One of the reasons why the current wave of defaults has drawn so much attention is that many troubled platforms were pretty big,” Huang said. Some of the platforms violated the rules, pooling funds illegally, and some were suffering from China’s slowing economic growth and the ongoing deleveraging campaigns.

P2P lending has helped fund small-to-medium-sized enterprises in some way, but in general, the role it plays in the financial system is limited, said Shen. Most of the P2P investors are speculative and they themselves should be responsible for their losses, he added.

“If the rate of return exceeds 6 percent, investors should be alert; if it is more than 8 percent, the investment is very risky, and if it’s more than 10 percent, investors should prepare themselves for losing all their capital,” said Guo Shuqing, chairmen of China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission at a finance forum in June in Shanghai, referring to financial scams that lure investors in with high returns.

Although P2P lending is only a relatively small piece in China’s financial industry, there are still concerns that the collapse of these platforms should trigger systematic risks, Shen said. This also implied that Chinese investors have very limited investment options.

According to research by China International Capital Corporation, experts predicted only 10 percent of the current P2P lending companies, less than 200, could still be in business after three years.

Zhang said P2P lending needs regulations because many platforms are not innocent. “P2P platforms have high moral hazards and it’s really easy to fake borrowers’ information. However, I believe the government is supportive towards the industry and some platforms will survive till the end,” said Zhang. “I just wish I can be lucky enough to pick the right one.”