The CEO and COO are at their desks when I knock on the door, intently assembling robots to fulfill the company’s latest order. Tapster is about as lean as startups get. Founded three years ago (on Star Wars Day), the company’s two-person staff is half the size it was at its height, but a third employee moved on, and the fourth was more of an intern, really.

It’s a humble operation headquartered in nondescript strip of stores in Oak Park, a quiet suburban village just outside of Chicago. Inside, a row of desktop 3D printers churn away on the products. Pieces of future robots are strewn about the desks, pulled from nearby shelves stocked with bins full of parts.

To their right, crumbling wooden prototypes stand as a kind of museum to the humble company’s even humbler origins. An accidental startup of sorts, Tapster formed while Jason Huggins was working as CTO of his previous company, Sauce Labs — a Selenium testing startup.

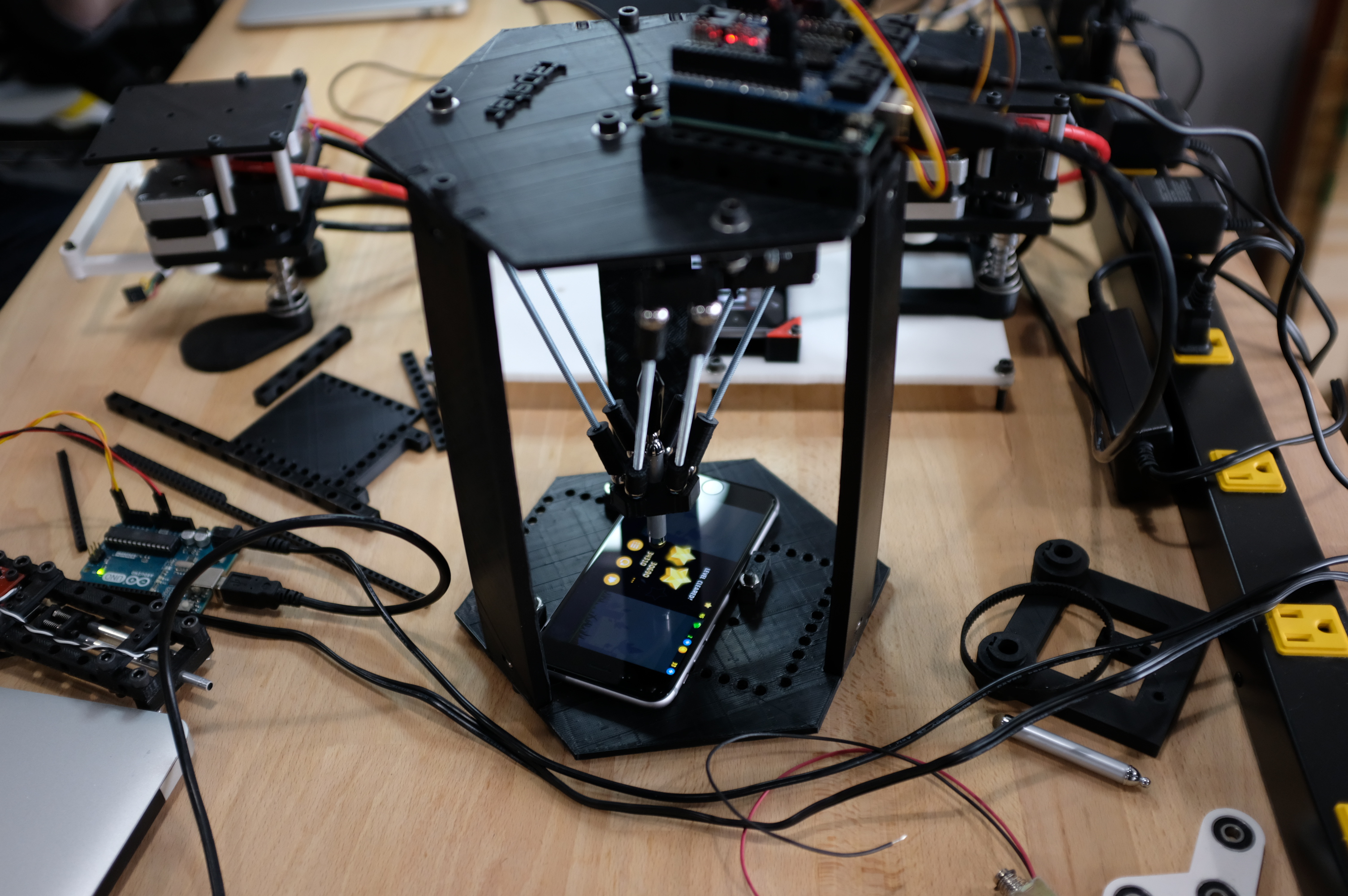

Burned out from software, the story goes, he enrolled in a laser cutting class at bygone maker space chain, Tech Shop. With those newfound skills, he built a button-clicking robot, and then, eventually, one capable of playing Angry Birds — all the rage back in 2011.The project gave Huggins a small YouTube hit and earned him speaking gigs at various tech conferences.

It also managed to grab the attention of Mercedes-Benz. The luxury car maker was searching for an automated device to help test a self-parking app on its in-car touchscreen displays.

“They got a price quote from an industrial robotics company, and the quote was about $100,000,” says Huggins. “They have lots of money and they could have bought it, but they had to get like 10 of them. The traditional robotics market is buying one big machine to do something precisely. We’re coming in and making the robots cheaper, so you can buy more of them.”

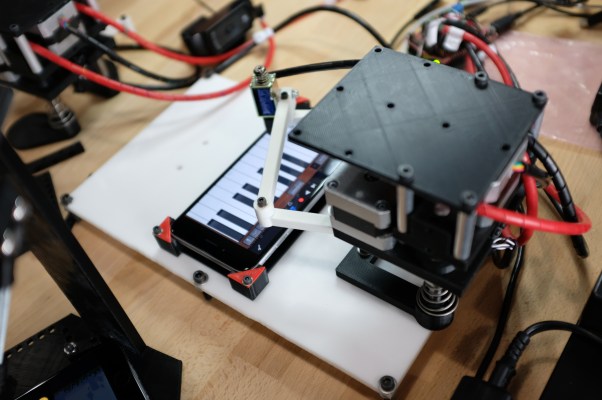

A few months prior to officially founding the company, Huggins began work on his order for the car maker — 10 small robots designed to automate the testing of touchscreens by repeatedly and systematically tapping the hell out of them.

“Right before they found us, they were going to buy a LEGO Mindstorm kit and have two engineers work on it for five or six months and figure out what they could come up with,” Huggins adds. “Often our competition is do-it-yourself. They’re trying to bubblegum and duct tape something together.”

Granted, Tapster’s own processes aren’t too far removed. Huggins is a former Google Tester who’s become something of a full-time tinkerer, building robots from LEGO kits and self-modeled 3D-printed parts. He shows me a prototype of the company’s latest robot, which stands on a pair of Ronald McDonald feet.

“I couldn’t find clown shoes on Thingiverse,” he tells me, excitedly. “So I made them. If you look up ‘Clown Shoes,’ you’ll find mine.”

These sorts of automated robotics are common for hardware manufacturers looking to test touchscreens. And while Tapster’s offerings are admittedly less sophisticated that the single service industrial robotics being deployed by larger organizations, Tapster is able to deliver their highly specialized product for a fraction of the cost.

Huggins hopes to one day make Tapster the go-to product for automated touchscreen testing, but for now, it’s baby steps. To date, the startup has functioned on a combination of self-funding, product sales and $100,000 in backing from Indie.vc, a micro venture firm that invests in “Real businesses want to stay in business, not run for the exit.”

“This is my second startup, and I’m really intentional about bootstrapping for as long as possible,” says Huggins. “I’m not anti-VC, but I’m definitely pro-having leverage. When you can walk in there say, ‘this is a train leaving the station and money can accelerate these trend lines,’ I’d like to be in that situation. That means I have to do more things longer. I’m not going out there and raising a seed round and hiring. I want to have a solid business I can hire into.”