It seems obvious that the way a robot moves would affect how people interact with it, and whether they consider it easy or safe to be near. But what poses and movement types specifically are reassuring or alarming? Disney Research looked into a few of the possibilities of how a robot might approach a simple interaction with a nearby human.

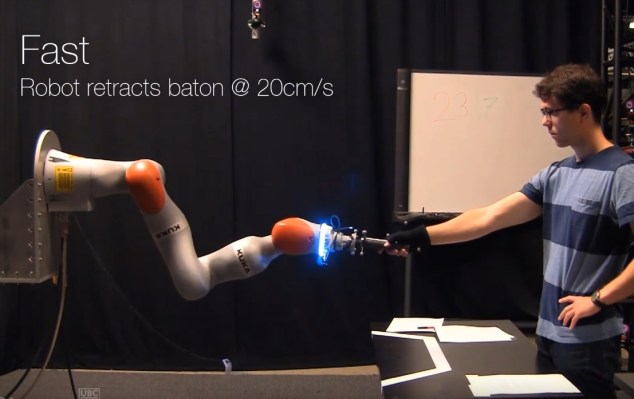

The study had people picking up a baton with a magnet at one end and passing it to a robotic arm, which would automatically move to collect the baton with its own magnet.

But the researchers threw variations into the mix to see how they affected the forces involved, how people moved and what they felt about the interaction. The robot had two types each of three phases: movement into position, grasping the object and removing it from the person’s hand.

For movement, it either started hanging down inertly and sprung up to move into position, or it began already partly raised. The latter condition was found to make people accommodate the robot more, putting the baton into a more natural position for it to grab. Makes sense — when you pass something to a friend, it helps if they already have their hand out.

Grasping was done either quickly or more deliberately. In the first condition the robot’s arm attaches the magnet as soon as it’s in position; in the second, it pushes up against the baton and repositions it for a more natural way to pull out. There wasn’t a big emotional difference here, but opposing forces were much less in the second grasp type, perhaps meaning it was easier.

Once attached, the robot retracted the baton either slowly or more quickly. Humans preferred the former, saying that the latter felt as if the object was being yanked out of their hands.

The results won’t blow anyone’s mind, but they’re an important contribution to the fast-growing field of human-robot interaction. Soon there ought to be best practices for this kind of thing for when we’re interacting with robots that, say, clear the table at a restaurant or hand workers items in a factory. That way they’ll be operating with the knowledge that they won’t be producing any unnecessary anxiety in nearby humans.

A side effect of all this was that the people in the experiment gradually seemed to learn to predict the robot’s movements and accommodate them — as you might expect. But it’s a good sign that even over a handful of interactions a person can start building a rapport with a machine they’ve never worked with before.