Note: This is the second article in a three-part series on valuation thoughts for common sectors of venture capital investment. The first article, which attempts to make sense of the SaaS revenue multiple, can be found here.

The two most highly valued private tech companies (outside of China) are Uber and Airbnb, checking in with valuations of $69 billion and $31 billion, respectively (according to the Crunchbase Unicorn leaderboard). Like some of the most valuable companies in the world (Alibaba, Facebook, and Google), both also happen to be marketplace businesses, and their success has helped encourage a rush of venture capital investment in similar business models over the past several years.

However, despite all this investment, public comps for marketplaces remain far thinner than those for SaaS — as of early January 2018, there were 42 publicly traded billion-dollar SaaS companies*, whereas only 14 marketplaces have broken this barrier**.

In addition, across these 14 companies, a few are international and thinly traded, and several others have different business models, with some driven by enterprise subscriptions (Zillow, Shutterstock, Yelp) and others purely by a take-rate (Grubhub, Etsy and eBay). As a result, despite being among the most popular categories of VC investment, few people truly understand how marketplace companies are valued in the public markets. It is through this lens that I felt an exploration of some of their characteristics and valuations would be an interesting topic to explore.

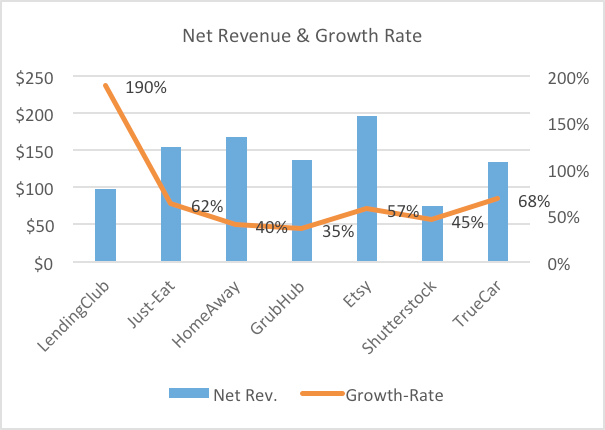

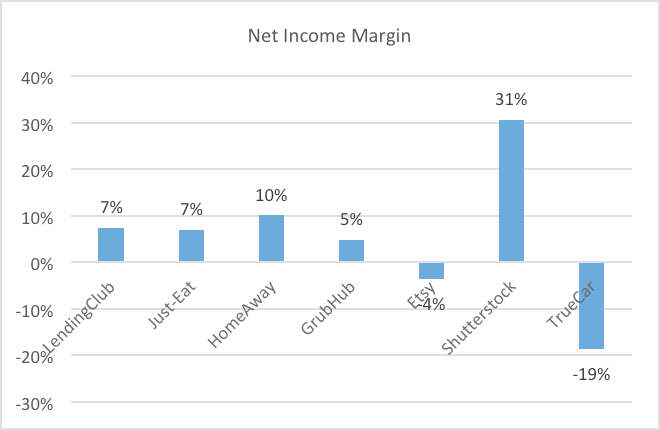

At the highest level, marketplace IPOs over the past few years have looked attractive. As you can see from the charts below, the average IPO had about $140 million in net-revenue, grew about 70 percent annually and produced 5 percent profit margins! This seems to represent a more attractive investment target than the average SaaS IPO, which checked in with median revenues around $100 million, grew about 60 percent and generally wasn’t profitable.

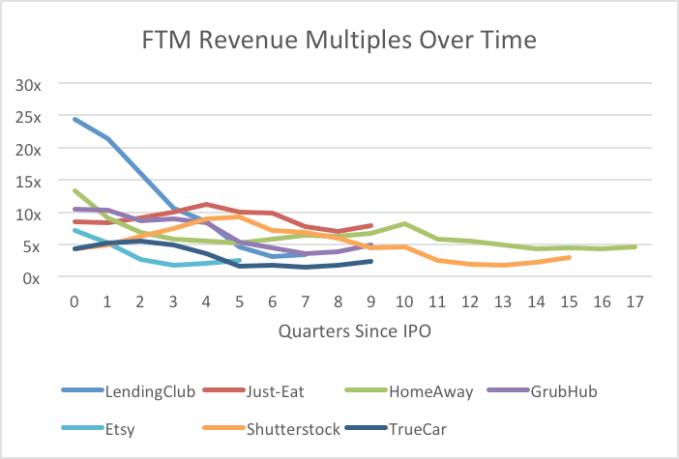

Initially, the public markets seemed to jump on the bandwagon, rewarding these marketplace IPOs with what looked like a healthy SaaS multiple — 10x+ on forward net revenues. However, with a combination of slowing growth, increased marketing spend and various levels of missed execution, the Street quickly soured on this crop of companies, and their forward multiple was slashed in half, to ~5x just five quarters later.

Today, with significantly slower growth (~20 percent), the median public marketplace trades at 4.4x forward revenue.

| Company | Mkt. Cap ($B) | 2018 Rev. ($M) | Growth | 2017 FCF Margin | FTM Rev. Mult. |

| Shutterstock | 1.5 | 607 | 10.6% | 8% | 2.5 |

| Just Eat | 7.5 | 888 | 25.2% | 20% | 8.4 |

| LendingClub | 1.7 | 692 | 20.1% | 2.5 | |

| Grubhub | 6.3 | 928 | 36.7% | 18% | 6.8 |

| Zillow | 8.0 | 1,295 | 20.8% | 17% | 6.2 |

| Etsy | 2.5 | 520 | 19.0% | 6% | 4.8 |

| TrueCar | 1.2 | 367 | 14.0% | 2% | 3.1 |

| TripAdvisor | 4.8 | 1,601 | 3.7% | 12% | 3.0 |

| Yelp | 3.6 | 954 | 13.2% | 18% | 3.8 |

| eBay | 41.5 | 10,240 | 7.1% | 24% | 4.1 |

| Priceline | 88.9 | 14,362 | 14.2% | 33% | 6.2 |

| Expedia | 19.4 | 11,343 | 12.3% | 9% | 1.7 |

| Delivery Hero | 7.1 | 909 | 39.6% | -34% | 7.8 |

| Takeaway.com | 2.6 | 273 | 38.6% | -13% | 9.5 |

| Mean | 20% | 9% | 5.0 | ||

| Median | 17% | 12% | 4.4 | ||

| High | 40% | 33% | 9.5 | ||

| Low | 20% | 9% | 5.0 | ||

Compared to the median SaaS company, which, trades at 5.8x forward revenue*, this 25 percent discount seems rather punitive. After all, marketplaces are generally more profitable than SaaS companies, likely require less engineering resources to deal with complex enterprise needs and are highly sticky over long periods of time. This stickiness results from the network effects inherent within marketplace businesses, which are typically not present in SaaS companies (with the exception of a Salesforce-like platform).

Think about your last experience on eBay or Craigslist — if you were like me, you fought through a terrible platform and user experience and may have vowed never to use the marketplace again. However, those pesky network effects made it such that the next time you need to offload that used sports equipment, you’ll have no choice but to turn to these old businesses with superior liquidity. Finally, many of these consumer marketplaces are catering to the vast addressable market of consumer spending; the S1’s of HomeAway, Grubhub and Etsy boast TAMs of $85 billion, $67 billion and $30 billion, respectively. Few enterprise software categories can believably lay claim to such a large opportunity.

So, why this discount? As discussed in my prior piece, for SaaS companies, it’s all about the cash flow. When we stack the free cash flow and growth metrics of public SaaS and marketplace companies against each other, we see that while the median marketplace produces slightly more cash flow, the average SaaS company grows faster. To get an apples-to-apples comparison, recall from my previous article that each percentage point less of SaaS growth simplistically adds about 1.4 percent to the bottom line (with an assumed payback period of 16 months).

| FCF Margin | Growth | Multiple | |

| SaaS | 10% | 23% | 5.8 |

| Marketplace | 12% | 17% | 4.4 |

| SaaS (Adj) | 18% | 17% | – |

Median numbers shown*

Now we can see that at growth-parity (assumed to be 17 percent), the median SaaS company generates 50 percent more free cash flow than the median marketplace company (18 percent versus 12 percent)! Clearly, the beauty of recurring revenue takes hold over time, as many SaaS businesses retain more than 100 percent of existing customer revenue and, as a result, are able to grow more efficiently. With sporadically returning customers, marketplaces simply need to invest more in marketing to fill their coffers each year, and never quite get on the same glide path as a SaaS business. From 2015 to 2016, eBay squeaked out a 4.5 percent gain, from $8.6 billion to $9.0 billion, while Salesforce continues to grow at a 25+ percent clip, pushing FY 2017 revenues to $8.4 billion (from $6.7 billion).

So, looking purely at the metrics, the SaaS premium over marketplaces seems to hold up to scrutiny. However, given the relative sparsity of marketplace comps in the public markets today, I suspect we will learn much more over the next few years as (knock on wood) a significant crop of private marketplaces hits the public markets.

With marketplaces like Uber and Amazon (which features a significant marketplace business) likely exhibiting customer expansion over time, the combination of SaaS-like upsell and a massive addressable market may earn premium multiples for a new breed of marketplaces. Led by a combination of new entrants and the continued strength of existing businesses, it’s entirely possible that marketplaces will again have their day in the sun!

Coming Up: Next month, my third installment in this series will cover valuation thoughts for arguably the least-loved category of venture capital investment — hardware.

*Source: BVP Cloud Index as of January 2018

**Excluding Facebook, Google, Amazon and Alibaba, which are highly diversified businesses and have unique business models.