Yesterday, I hailed a ride in San Francisco and got to my destination and back without the help of a human driver.

GM’s Cruise has a fleet of self-driving cars pretty much continually roving the streets of San Francisco, gathering data and improving their autonomous driving performance with the ultimate goal of underpinning future commercial self-driving products from the automaker. Thus far, employees and investors have had the chance to take rides in the test vehicles – but no one outside the company has had that opportunity, until Cruise gave myself and a handful of other journalists rides around the city this week.

The ride in the modified Bolt EV, a second-generation Cruise test car (only a few of the third-generation vehicles are on roads at the moment, with plans to produce more very soon) involved hailing a car to a location in San Francisco’s Dogpatch neighborhood, selecting from one of three available destinations, and then loading into the vehicle to make the trip.

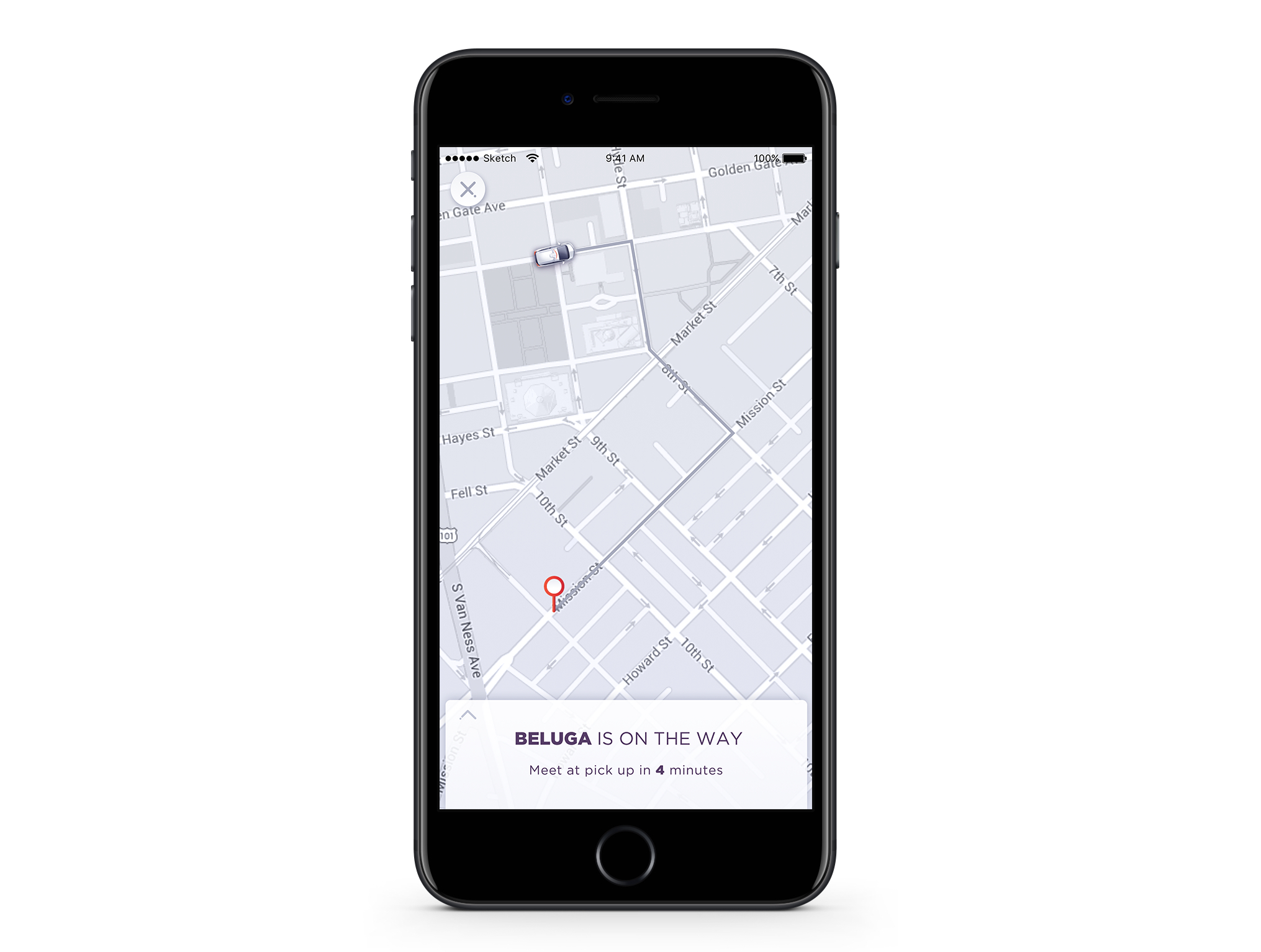

Cruise’s app (on staff iPhones) resembled other ride hailing apps you’ve probably encountered, mostly taken up by a map and featuring simple interface elements to initiate the hail and notify you when the vehicle arrived. One of Cruise’s user experience designers explained that the app we saw was basically the same as the one that Cruise employees are able to use now to hail rides, which are made available on a first come, first service basis.

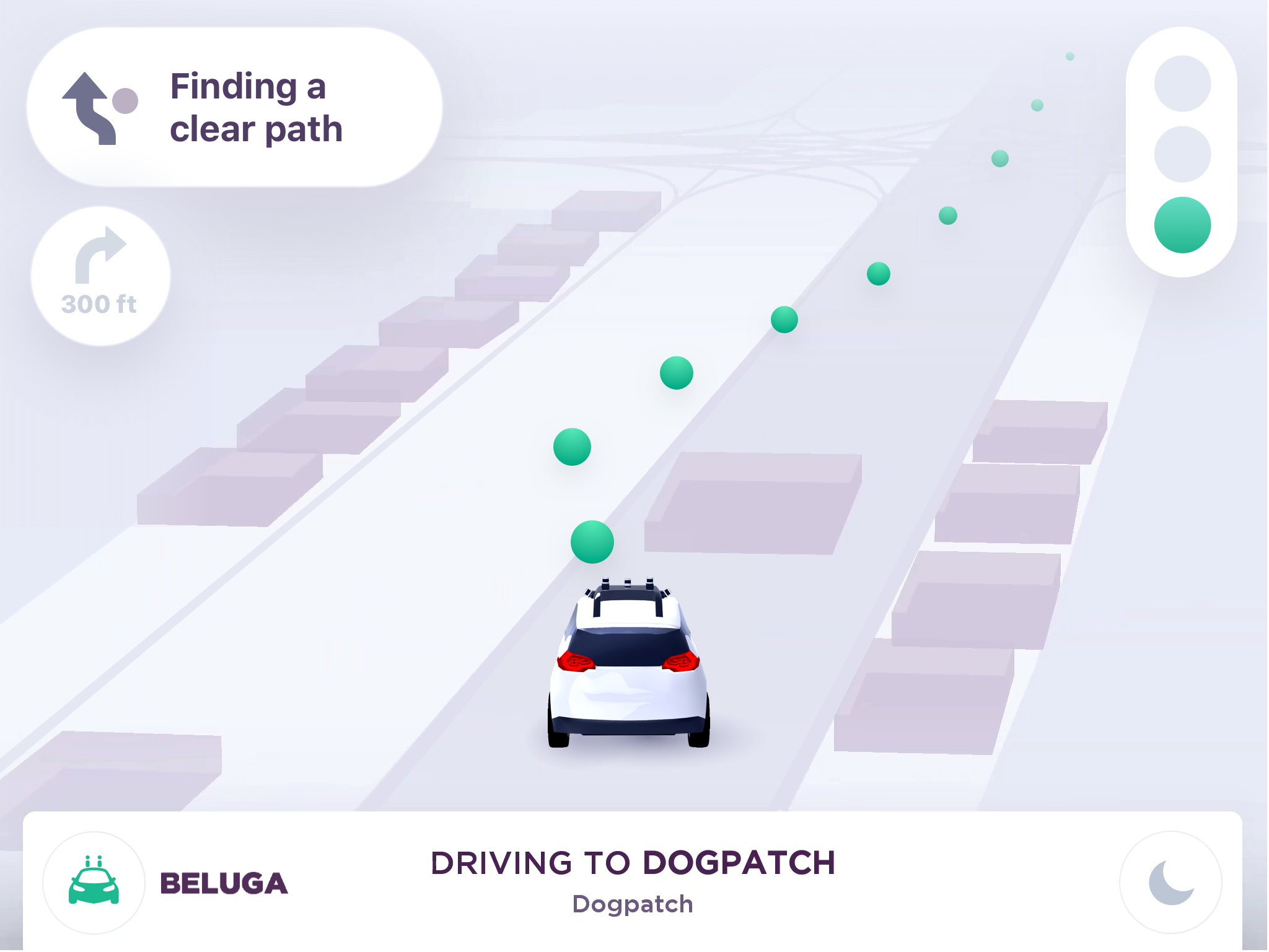

In-car, the same basic design elements are used to populate two tablet displays mounted on the driver and front passenger seat headrests, and another center-mounted tablet up front. These first inform you to buckle your seatbelt, and then also show live information fed by the car’s sensors and onboard computer, including detected buildings, other vehicles on the road, pedestrians and cyclists.

The in-vehicle displays also show you info about the upcoming turns, merges and other navigation details so you know what’s coming, and what the car is doing in terms of deciding its route. A line of green bubbles projects its immediate course, and the color lets you know that the self-driving system is engaged and working.

Other indicators pop up as needed, including brief explanations of unexpected pauses, and traffic light status for when you’re stopped at an intersection. It’s a pretty spare interface, but it answers most questions you have about what the car is doing and why without any information overload.

During the course of my ride, which spanned about 15 to 20 minutes and 2.4 miles of driving, I definitely sought out the display for additional context on some of the driving ‘choices’ made by the Cruise test car. Ahead of our ride, Cruise founder Kyle Vogt cautioned us that the cars were optimized for safety first, not for comfort (only two percent of its development time thus far has been focused on comfort, vs. the vast majority devoted to safety, he said), and the vehicle slowed or stopped unexpectedly a couple of times with more sudden deceleration than I’d have expected from a human taxi, Uber or Lyft driver in the same circumstances.

In one such instance, the Cruise test car stopped when there was a cherry picker extending into the lane on the right, and a vehicle coming up behind. It opted to pause for a moment, activate its blinkers and let the approaching vehicle past while it determined how best to pass the cherry picker, though there wasn’t any oncoming traffic and plenty of room on the left. The car seemed very clearly to be evaluating its options, and making the call to pursue the safest course of not doing anything until it was sure it had made the correct analysis of its current situation.

Even with this pause, however, the self-driving system didn’t disengage and the safety drivers (technically ‘Autonomous Vehicle Trainers,’ including the driver and an analyst in the passenger seat) never had to assume manual control. This was the defining, and most significant takeaway from the trip – it managed downtown San Francisco without human intervention, across a range of different challenges including pedestrians crossing in front of us in the middle of the street, bike riders intersecting our path and construction blocking much of the vehicle’s designated lane.

That’s in stark contrast to the last ‘autonomous’ test ride I took in SF – in Uber’s autonomous Volvo SUV last year. That involved frequent disengagements from the safety driver, which made Cruise’s demo seem miles ahead in terms of technological maturity by comparison.

Compared to rides in Waymo’s vehicle (on a closed course, at its Castle testing facility), Cruise’s ride felt slower, more erratic and less ‘human’ – but according to both GM and Cruise, the focus right now is on the major technical hurdle of safety and achieving human level proficiency, with considerations like ‘comfort’ ranking much higher up on the ‘hierarchy of needs for self-driving,’ and therefore extending further out in terms of development priorities.

Riding in Cruise’s vehicle ultimately left me at no time feeling concerned for my safety or wellbeing, or for the safety of those around me. It did once proceed on a right turn at an intersection when a pedestrian had already entered the crosswalk at the far end of the crossing, which is something I’d expect from human drivers but something that might not strictly be in keeping with the rules of the road in California. Again, it was what I likely would’ve done in the same situation, given the gap between the car and the pedestrian, but it seemed slightly at odds with the system’s practice of exercising an abundance of caution at all times.

Did riding in Cruise’s test vehicle make me feel like autonomous driving is close in terms of being something commercially available? Despite a few hiccups, it did: This is what a startup managed to build in just three years, after all – a car that can navigate a busy route, sharing the road with 114 cars, 4 bikes and a number of pedestrians over the course of 2.4 miles (yes, they really kept count) while operating fully autonomously. If Cruise can manage to make that happen in three years, then imagining what it can do in three more makes me optimistic about seeing self-driving become a transformative experience for a large number of people.