New CEO Dara Khosrowshahi has been vocal in pledging to reform Uber’s toxic culture to take the business to the next level — and ultimately an IPO — but, over in Asia, another recent arrival is presiding over a revamped approach which includes turning those who were once enemies into friends.

Brooks Entwistle, a former Chairman of Goldman Sachs Southeast Asia, joined the firm in August to lead its business in Asia Pacific, minus China — where it sold to rival Didi — and India, where the firm is run by a dedicated country president.

At the time of his arrival I joked that Entwistle, who has lived across Asia for over two decades, may need to dip into his experience of scaling Mount Everest such is the challenge of handling Uber’s business in Asia. This year alone, it has been rocked by scandals that include using unsafe cars in Singapore, bribery allegations in at least five countries, not to mention ongoing skirmishes with regulators in countries that include Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Thailand and Indonesia.

Then there’s the competition.

Singapore-based rival Grab seems to have taken the lead regionally, and it recently refueled with $2 billion in fresh capital. In Indonesia, Southeast Asia’s largest economy, local firm Go-Jek leads and it has raised more than $1 billion with support from Chinese giant Tencent.

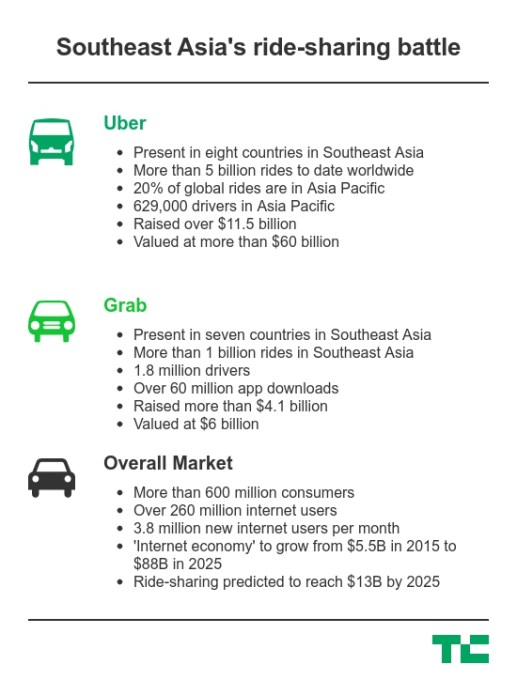

Uber seems a little off the pace in Southeast Asia, a region of over 600 million consumers where the ride-sharing economy is tipped to grow five-fold to reach $13.1 billion and 29 million customers over the next decade.

Grab recently celebrated crossing one billion rides and it claims over 60 million users and 1.8 million drivers. Uber told TechCrunch that it doesn’t provide regional data, but it did share that Asia Pacific as a whole represents over 20 percent of its global trip volume. The region, Uber added, has nearly 629,000 active drivers, which it said is over 25 percent of its global driver network. Uber crossed five billion rides worldwide at the end of June 2017.

Beyond the numbers, Go-Jek and Grab have expanded their services beyond cars — moving into areas like mobile payments to grow engagement and even bike-sharing — and invested heavily in local R&D and developer talent to build platforms that are more significant than merely hailing a ride.

Uber hasn’t followed suit, but the competition — while never named directly — appears to have been watched. Indeed, if Entwistle has his way, the U.S. firm will modernize its business accordingly, too, and branch out into new areas it would likely never have considered in order to remain competitive and relevant.

Beyond private cars

In an interview with TechCrunch, U.S.-born Entwistle — Uber’s Chief Business Officer for Asia Pacific — confirmed that the firm is looking into opportunities within adjacent that include payments and bike-sharing.

“Already we’re thinking about technologies and solutions across the region that will ease any transaction friction. We try to find whatever the best way to get people on to our app riding or driving… [that] could take number of different forms,” Entwistle said when asked about whether Uber might do deals with payment companies.

Brooks Entwistle joined Uber as its Chief Business Officer for Asia Pacific in August 2017

In China, Didi Chuxing — often a bellwether for where the industry is headed — first invested in bike sharing startup Ofo more than a year ago and, sensing the potential of the travel option, it integrated the service into its app to offer an alternative for commuters.

That deal appears to be an astute one. Not only has Ofo raised more money at a valuation of over $1 billion, but bike-sharing has begun to take a bite out of the on-demand ride business in China where it offers an alternative for short trips.

There’s plenty of uncertainty as to whether these businesses can thrive outside of China, which is known for its affinity for bikes, but that hasn’t stopped them from venturing overseas alongside a glut of international clones.

Grab, which counts Didi as an investor, isn’t taking a chance and it quietly backed one Ofo clone, a Singapore startup called oBike, as TechCrunch recently reported.

While Grab and oBike haven’t worked together yet, it is almost certain to be on the cards sooner or later. At that point Grab might find that its two-wheeled ambition is matched by Uber.

“It’s something we’re looking at [because] we know it’s an important way of getting around,” Entwistle told TechCrunch. “We have a team focused [on investigating bike-sharing options] from a business development standpoint.”

From enemy to partner

Bicycles might be an unexpected move for Uber — which has autonomous vehicles in the U.S. and is even working with NASA to look into flying taxis — but the company has become open to new concepts when it comes to transportation across Asia since it entered via Singapore in February 2013.

For one thing, it supports cash-based payments across much of Southeast Asia, in addition to India and parts of Africa. That was once unthinkable since Uber existed to rid the world of a need for cash. Beyond that, even the type of rides it covers have changed.

Uber has even struck deals with local taxi companies.

Once the enemy, a combination of factors — which primarily include driver supply constraints and tight regulations — have led to Uber taxi services sprouting up in Korea, Taiwan, Myanmar, Indonesia among other places.

Unlike previous Uber’s regimes — which rivaled traditional taxis by being cheaper and easier to hail — Entwistle said that doing deals with the former foe is now “a big focus.”

“We are actively looking to partner with taxi companies,” he said. “In Taipei [where Uber recently began working with taxi partners], taxis are at 30 percent utilization, we can drive that [figure] up.”

Working with Uber — which has been the target of taxi driver rage across Asia — may represent an opportunity, but doing deals is not straightforward as a recent example in Singapore shows.

When Comfortdelgro, the city’s largest taxi operator with over 15,000 vehicles, announced in August that it was in talks with Uber over a “potential strategic alliance” that could double Uber’s driver network, rival Grab began aggressively poaching the taxi firm’s drivers to water down the impact of a potential alliance, one source told TechCrunch.

No deal has been announced and it is unclear whether it will come to fruition. If so it would mark a very clear step into Grab’s territory. The company began life as a platform for licensed taxis before expanding into Uber-style private vehicles, and it still enjoys relationships with Singapore’s other taxi operators.

Uber returned to Taiwan in partnership with local taxi operators [Image via: SAM YEH/AFP/Getty Images]

Governments as allies

Uber has also run into challenges with its adoption of motorbike taxis, a popular mode of transport for quickly getting from A to B in the congested streets of Southeast Asia’s megacities.

Its UberMoto service was ended in Bangkok just three months despite representatives of capital city Bangkok’s police force taking part in the launch event. Grab relaunched its competing motorbike service through a partnership with local government-approved bike taxi drivers, while Uber’s recently returned using a similar partner but it is limited to the central business district. It also offers motorbike taxis in Indonesia, India and Vietnam, however.

Learning from that episode and others like it, regulators and governments have become a key stakeholder for Uber. In recent years, the U.S. firm has shifted from an aggressive strategy in its homeland where it has little regard for “antiquated” regulations, to a more conciliatory approach in Asia.

Under Entwistle that focus is about to get a whole lot more sharper.

“I visit one or two countries a week to meet regulators and governments,” he said. “We talk solutions and are coming at this from a collaboration/partnership approach. The conversation feels like it is really changing.”

Recent launches in Yangon in Myanmar and Phnom Penh in Cambodia — two relatively over-looked countries — best epitomize this new-found strategy of working with governments. In the case of both market expansions, Uber sought (and heavily publicized) endorsements from government officials and the U.S. ambassadors of the respective countries.

That’s a huge departure on its previous playbook of bootstrapped and secretive launches which often flew in the face of local government or regulators. The new approach seems to be an inevitable reaction to the fact that the old method simply doesn’t work in this part of the world, especially when Grab is prepared to work with regulators.

“We launched fully in [Cambodia] in cooperation with the government,” Entwistle, who was speaking from Uber’s Vietnam office following a meeting with regulators, told TechCrunch.

“Transportation officials were on stage and it is very much a partnership. I do think we have to work with them to provide solutions, and we are asking them in many cases what they need,” he added.

Uber received a mention on the (very active) Facebook Page for Cambodia’s Ministry of Public Works and Transportation after an initial agreement to launch was struck.

That’s exactly the aim on Uber’s new campaign around easing urban congestion across the region, and particularly Southeast Asia. The company is positioning itself as an ally that can help governments, regulators and city planning teams tackle urban congestion and reduce the amount of cars on the road across Southeast Asia.

“It’s about unlocking cities,” said Entwistle.

Catching up in Southeast Asia

The creative video in support of Uber’s big push came out the very day that Grab announced its foray into mobile payments. The move will allow users, initially in Singapore, to buy items from physical retail stores using the Grab app and QR codes in the same style as Alipay, WeChat and others.

The initial 26 participating merchants are all street food vendors, but Grab hopes to grow the number to 1,000 and branch out into other types of commerce. The company added that it will expand the initiative to more of its six other markets in 2018.

The disparity between the news issued that day — a video versus a fintech platform — illustrates that Uber is playing catch-up.

The good news for Uber is that, despite reports that some shareholders would consider a deal with Grab, its business and brand is still healthy in the region. Its marketshare is likely closer than many believe — accurate data is at a premium — but it does appear to be trailing in the ideas and execution department. An injection of fresh perspective might make things interesting as it looks to up the ante with Grab — and potentially in other parts of the world for its business.

“There are things we are doing here that we believe are relevant and will be adopted elsewhere,” Entwistle explained.

That might give some leeway for experimentation.

The immediate future for Southeast Asia could be better for Uber, however. While TechCrunch understands that some country offices have been operationally profitable for more than a year, CEO Khosrowshahi indicated that it is losing money across the Southeast Asian region as a whole.

“The economics of that market are not what we want them to be,” he told an audience at the New York Times DealBook conference. “I think it’s over-capitalized at this point. We’re going in, and we’re leaning forward. But I‘m not optimistic that market is going to be profitable any time soon.”

With an IPO coming tentatively slated for 2019, developing the business through this revised approach under Entwistle is essential to ensuring that Uber still has enough reason to care about remaining in Southeast Asia and other parts of Asia. Otherwise, if Lyft continues to gain in the U.S., the management may opt to deploy its resources in other areas, a move that would be much to the detriment of Southeast Asia as a whole.