The thorny issue of tracking of location data without risking individual privacy is very neatly illustrated via a Freedom of Information (FOI) request asking London’s transport regulator to release the “anonymized” data-set it generated from a four week trial last year when it tracked metro users in the UK capital via wi-fi nodes and the MAC address of their smartphones as they traveled around its network.

At the time TfL announced the pilot it said the data collected would be “automatically de-personalised”. Its press release further added that it would not be able to identify any individuals.

It said it wanted to use the data to better understand crowding and “collective travel patterns” so that “we can improve services and information provision for customers”.

(Though it’s since emerged TfL may also be hoping to generate additional marketing revenue using the data — by, a spokesman specifies, improving its understanding of footfall around in-station marketing assets, such as digital posters and billboards, so not by selling data to third parties to target digital advertising at mobile devices.)

Press coverage of the TfL wi-fi tracking trial has typically described the collected data as anonymized and aggregated.

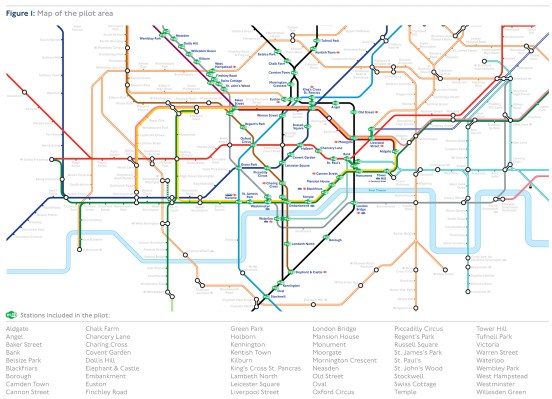

Those Londoners not wanting to be tracked during the pilot, which took place between November 21 and December 19 last year, had to actively to switch off the wi-fi on their devices. Otherwise their journey data was automatically harvested when they used 54 of the 270 stations on the London Underground network — even if they weren’t logged onto/using station wi-fi networks at the time.

However in an email seen by TechCrunch, TfL has now turned down an FOI request asking for it to release the “full dataset of anonymized data for the London Underground Wifi Tracking Trial” — arguing that it can’t release the data as there is a risk of individuals being re-identified (and disclosing personal data would be a breach of UK data protection law).

“Although the MAC address data has been pseudonymised, personal data as defined under the [UK] Data Protection Act 1998 is data which relate to a living individual who can be identified from the data, or from those data and other information which is in the possession of, or is likely to come into the possession of, the data controller,” TfL writes in the FOI response in which it refuses to release the dataset.

“Given the possibility that the pseudonymised data could, if it was matched against other data sets, in certain circumstances enable the identification of an individual, it is personal data. The likelihood of this identification of an individual occurring would be increased by a disclosure of the data into the public domain, which would increase the range of other data sets against which it could be matched.”

So what value is there in data being “de-personalized” — and a reassuring narrative of ‘safety via anonymity’ being spun to smartphone users whose comings and goings are being passively tracked — if individual privacy could still be compromised?

At this point we’ve seen enough examples of data sets being sold and re-identified or shared and re-identified that for large scale data-sets that are being collected claims of anonymity are dubious — or at least need to be looked at very carefully.

“At this point we’ve seen enough examples of data sets being sold and re-identified or shared and re-identified that for large scale data-sets that are being collected claims of anonymity are dubious — or at least need to be looked at very carefully,” says Yves-Alexandre de Montjoye, a lecturer in computational privacy at Imperial College’s Data Science Institute, discussing the contradictions thrown up by the TfL wi-fi trial.

He dubs the wi-fi data collection trial’s line on privacy as a “really thorny one”.

“The data per se is not anonymous,” he tells TechCrunch. “It is not impossible to re-identify if the raw data were to be made public — it is very likely that one might be able to re-identify individuals in this data set. And to be honest, even TfL, it probably would not be too hard for them to match this data — for example — with Oyster card data [aka London’s contactless travelcard system for using TfL’s network].

“They’re specifically saying they’re not doing it but it would not be hard for them to do it.”

Other types of data that, combined with this large scale pseudonymised wifi location dataset could be used to re-identify individuals, might include mobile phone data (such as data held by a carrier) or data from apps on phones, de Montjoye suggests.

In one of his previous research studies, looking at credit card metadata, he found that just four random pieces of information were enough to re-identify 90 per cent of the shoppers as unique individuals.

In another study he co-authored, called Unique in the Crowd: The privacy bounds of human mobility, he and his fellow researchers write: “In a dataset where the location of an individual is specified hourly, and with a spatial resolution equal to that given by the carrier’s antennas, four spatio-temporal points are enough to uniquely identify 95% of the individuals”.

Meanwhile, London’s Tube network handles up to five million passenger journeys per day — the vast majority of whom would be carrying at least one device with embedded wi-fi making their movements trackable.

The TfL wi-fi trial tracked journeys on about a fifth of the London Underground network for a month.

A spokesman confirms it is now in discussions, including with the UK’s data protection watchdog, about how it could implement a permanent rollout on the network. Though he adds there’s no specific timeframe in the frame as yet.

“Now we’re saying how do we do this going forward, basically,” says the TfL spokesman. “We’re saying is there anything we can do better… We’re actively meeting with the ICO and privacy groups and key stakeholders to talk us through what our plans will be for the future… and how can we work with you to look to take this forward.”

On the webpage where it provides privacy information about the wifi trial for its customers, TfL writes:

Each MAC address collected during the pilot will be de-personalised (pseudonymised) and encrypted to prevent the identification of the original MAC address and associated device. The data will be stored in a restricted area of a secure server and it will not be linked to any other data.

As TfL will not be able to link this data to any other information about you or your device, you will not receive any information by email, text, push message or any other means, as a result this pilot.

The spokesman tells us that the MAC addresses were encrypted twice, using a salt key in the second instance, which he specifies was destroyed at the end of the trial, claiming: “So there was no way you could ascertain what the MAC address was originally.”

“The only reason we’re saying de-personalized, rather than anonymized… is in order to understand how people are moving through the station you have to be able to have the same code going through the station [to track individual journeys],” he adds. “So we could understand that particular scrambled code, but we had no way of working out who it was.”

However de Montjoye points out that TfL could have used daily keys, instead of apparently keeping the same salt keys for a month, to reduce the resolution of the information being gathered — and shrink the re-identification risk to individuals.

“The big thing is whether — and one thing we’ve really been strongly advocating for — is to really try to take into account the full set of solutions, including security mechanisms to prevent the re-identification of [large scale datasets] even if the data is pseudoanonymous,” he says. “Meaning for example ensuring that there is no way someone can access, both the dataset or try to take auxiliary information and try to re-identify people through security mechanisms.”

“Here I have not seen anything that describes anything that they would have put in place to prevent these kind of attacks,” he adds of the TfL trial.

He also points out that the specific guidance produced by the UK ICO on wi-fi location analytics recommends data controllers strike a balance between the uses they want to make of data vs collecting excessive data (and thus the risk of re-identification).

The same guidance also emphasizes the need to clearly inform and be transparent with data subjects about the information being gathered and what it will be used for.

Yet, in the TfL instance, busy London Underground commuters would have had to actively switch off all the wi-fi radios on all their devices to avoid their travel data being harvested as they rushed to work — and might easily have missed posters TfL said it put up in stations to inform customers about the trial.

“One could at least question whether they’ve been really respecting this guidance,” argues de Montjoye.

TfL’s spokesman has clearly become accustomed to being grilled by journalists on this topic, and points to comments made by UK information commissioner, Elizabeth Denham, last month who, when asked about the trial at a local government oversight meeting, described it as “a really good example of a public body coming forward with a plan, a new initiative, consulting us deeply and doing a proper privacy impact assessment”.

“We agreed with them that at least for now, in the one-way hash that they wanted to implement for the trial, it was not reversible and it was impossible at this point to identify or follow the person through the various Tube station,” Denham added. “I would say it is a good example of privacy by design and good conversations with the regulator to try to get it right. There is a lot of effort there.”

Even so, de Montjoye’s view that large-scale location tracking operations need to not just encrypt personally identifiable data properly but also implement well designed security mechanisms to control how data is collected and can be accessed is difficult to argue with — with barely a week going by without news breaking of yet another large scale data breach.

Equifax is just one of the most recent (and egregious) examples. Many more are available.

While much more personal data is leeching into the public domain where it can be used to cross-reference and unlock other pieces of information, further increasing re-identification risks.

“They are reasonably careful and transparent about what they do which is good and honestly better than a lot of other cases,” says de Montjoye of TfL, though he also reiterates the point about using daily keys, and wonders: “Are they going to keep the same key forever if it becomes permanent?”

He reckons the most important issue likely remains whether the data being collected here “can be considered anonymous”, pointing again to the ICO guidance which he says: “Clearly states that ‘If an individual can be identified from that MAC address, or other information in the possession of the network operator, then the data will be personal data'” — and pointing out that TfL holds not just Oyster card data but also contactless credit and debit card data (bank cards can also be used to move around its transport network), meaning it has various additional large scale data-holdings which could potentially offer a route for re-identifying the ‘anonymous’ location dataset.

“More generally, the FOIA example nicely emphasize the difficulties (for the lack of a better word) of the use of the word anonymous and, IMHO, the issue its preponderance in our legal framework raises,” he adds. “We and PCAST have argued that de-identification is not a useful basis for policy and we need to move to proper security-based and provable systems.”

Asked why, if it’s confident the London Underground wi-fi data is truly anonymized it’s also refusing to release the dataset to the public as asked (by a member of the public), TfL’s spokesman tells us: “What we’re saying is we’re not releasing it because you could say that I know that someone was the only person in the station at that particular time. Therefore if I could see that MAC address, even if it’s scrambled, I can then say well that’s the code for that person and then I can understand where they go — therefore we’re not releasing it.”

So, in other words, anonymized data is only private until the moment it’s not — i.e. until you hold enough other data in your hand to pattern match and reverse engineer its secrets.

“We made it very clear throughout the pilot we would not release this data to third parties and that’s why we declined the FOI response,” the spokesman adds as further justification for denying the FOI request. And that at least is a more reassuringly solid rational.

One more thing that’s worthy of noting is that incoming changes to local data protection rules are likely to reduce some of the confusion in future, when the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) comes into effect across the European Union next May.

“I expect the GDPR, and the UK law implementing it, will make the situation around anonymity and pseudonymised data a lot clearer than it is now,” says Eerke Boiten, a cyber security professor at De Montfort University. “The GDPR has separate definitions of both, and does not make a risk-based assessment of whether pseudonymised personal data remains personal: It simply always is.

“Anonymised data under the GDPR is data where nobody can reconstruct the original identifying information — something that you cannot achieve with pseudonymisation on databases like this, even if you throw away the ‘salt’.”

“Pseudonymisation under the GDPR is essentially a security control, reducing in the first place disclosure impact — in the same way that encryption is,” he adds.

The UK is also considering changing domestic law to criminalize the re-identification of anonymous data. (Though de Montjoye voices concern about what that might mean for security researchers — and critics of the proposal have suggested the government should rather focus on ensuring data controllers properly anonymize data.)

GDPR will also change consent regimes as it can require explicit consent for the collection of personal data — though other lawful bases for processing data are available. So it seems unlikely that TfL could roll out a permanent system to gather wi-fi data on the London Underground in the way it did here, i.e. by relying on an opt-out.

“This would never be a ‘consent’ scenario under the GDPR,” agrees Boiten. “Failing to opt-out isn’t a ‘clear affirmative action’. For the GDPR, TfL would need to find a different justification, possibly involving their service responsibilities as well as the impact on passengers’ privacy. Informing passengers adequately would also be central.”

This article was updated to clarify that consent is one of the legal basis for processing personal data under GDPR — other legal basis do exist, although it’s not clear which of those, if any, TfL could use to process wi-fi location tracking data without obtaining consent