Magnetic storage, and we’re talking tape here, is good for long-term storage because it’s cheap and stable — unlike solid state drives and volatile memory, which are quick but expensive and better for temporary storage. New research might lead to a method that combines the best of both worlds.

The main problem with magnetic storage is that it tends to require a charged coil that must physically move to the location on the disk that it needs to write to and directly switch the direction of magnetization. Solid state storage lets the file system write to anywhere in its many gigabytes instantly. It’s like the difference between writing down an address and driving to it.

But if magnetic storage could be stored as addressable cells, it would be quick to write but would maintain its 1 or 0 status indefinitely. That’s what the researchers at ETH Zurich are attempting to do — and have done, at least with a single cell.

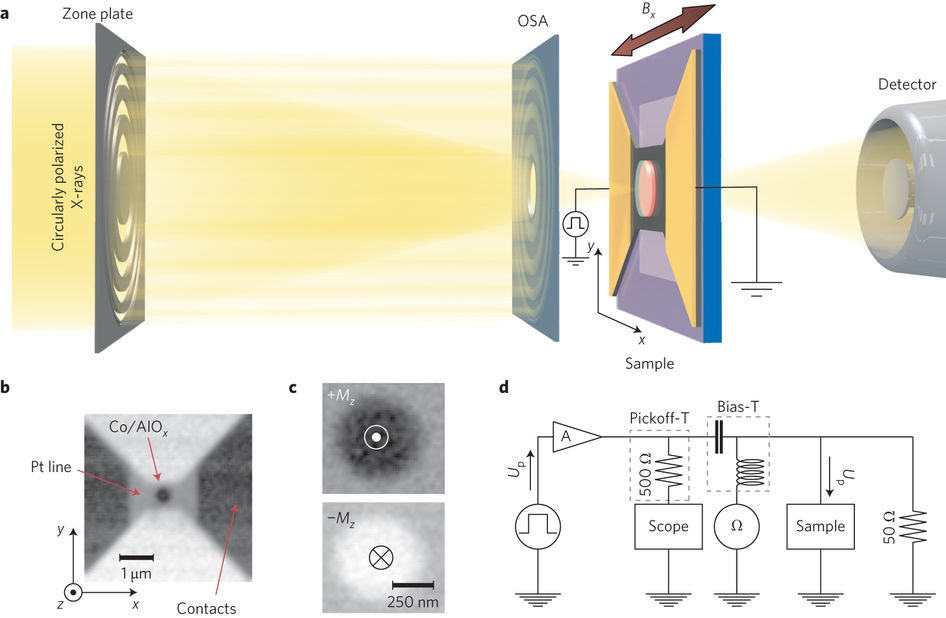

Instead of having a coil touch a magnetic medium, a tiny cobalt dot 500 nanometers wide sits near a platinum wire. When electricity flows through the wire, stray electrons with spin opposite that of the cobalt accumulate at the edge, and eventually cause the whole dot to flip its magnetic orientation.

The team demonstrated this back in 2011 but just published a new paper showing how fast this whole thing happens — they watched it by blasting it with a scanning microscopic x-ray machine, which is pretty awesome. Turns out the whole bit flipping process takes less than one nanosecond.

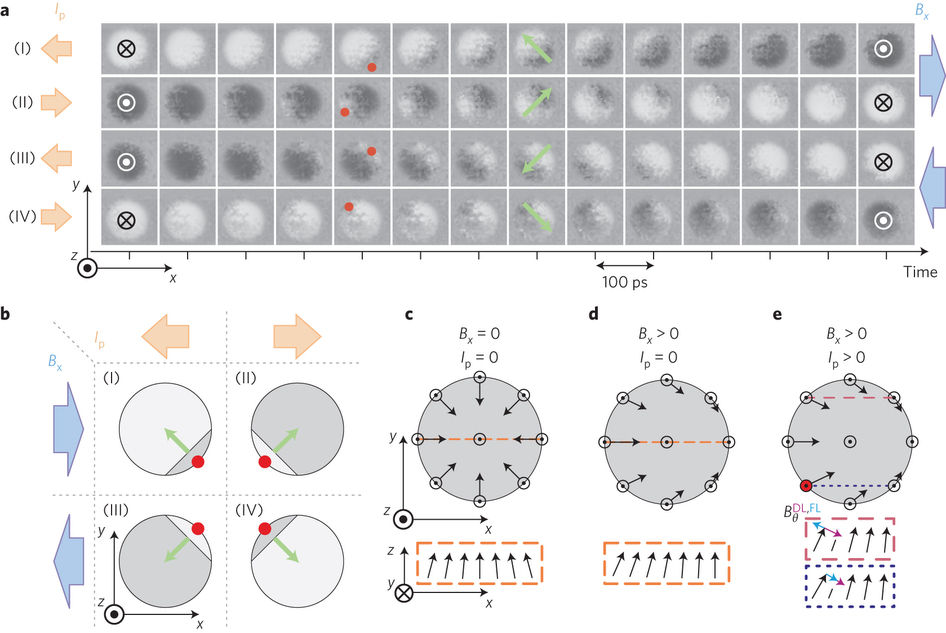

In this diagram from the paper, you can see how the dot flips from one magnetic moment to another in a progressive process taking less than a nanosecond.

Not only that, but they flipped it back and forth trillion (!) times at 20 million times per second, and observed nothing suggesting the effect was weakening or becoming unreliable.

They plan to make it even faster and work with a smaller current, and possibly change the shape of the dot — for all they know, a square might flip faster than a circle. My guess is that they’re putting off the really hard part, which is putting billions of these things in a huge, addressable array. Not much use storing a single 0 or 1 — I can do that with a coin.

Ultimately this or a technology like it could lead to instantly writable but enduring storage that requires no power to keep its data intact; it could be used as RAM or long term storage, assuming it gets cheap enough to use for either. That’s for them to figure out.

The research is detailed in the latest issue of the journal Nature Nanotechnology.