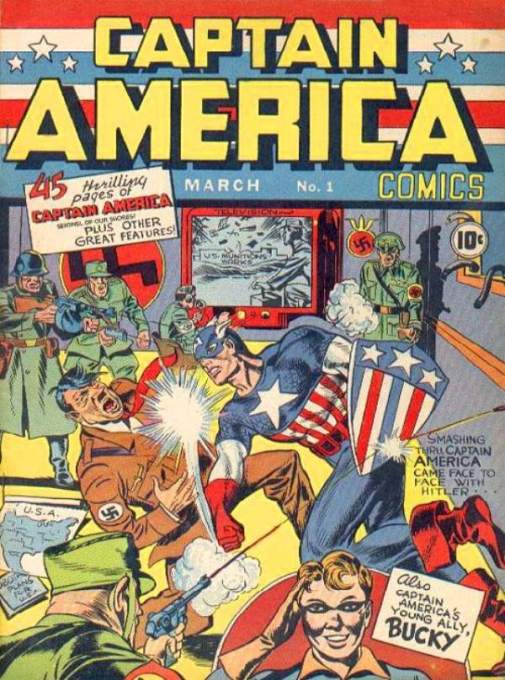

On the cover of his debut issue, Captain America is captured a fraction of a second after delivering a vicious right hook to Adolf Hitler’s toothbrush mustache. He appears unfazed — Zen-like, even — as four uniformed members of the Gestapo fire at him from all corners.

“Smashing thru,” the caption reads, “Captain America came face to face with Hitler … ” The 10-cent book appeared on store shelves a full year before Pearl Harbor officially woke the sleeping giant and forced America to enter World War II. He wasn’t the first superhero (that matter is indeed, the subject of much debate), though he would help usher in a new age for the genre. And there was little question that he — and by extension his creators, Joe Simon and Jack Kirby — knew how to make an entrance.

The Captain next returned in the mid-’60s, when the Silver Age of comics was at its apex. Once again, Kirby was there, returning to the superhero fold after working in western, romance and monster comics. In fact, the Fantastic Four, the Incredible Hulk, Thor, Spider-Man, Iron Man, the Avengers, the X-Men, Galactus, the Silver Surfer, the Black Panther, the Inhumans and many more were all created in the span of a few years, and almost entirely by three people — Kirby, Steve Ditko and Stan Lee.

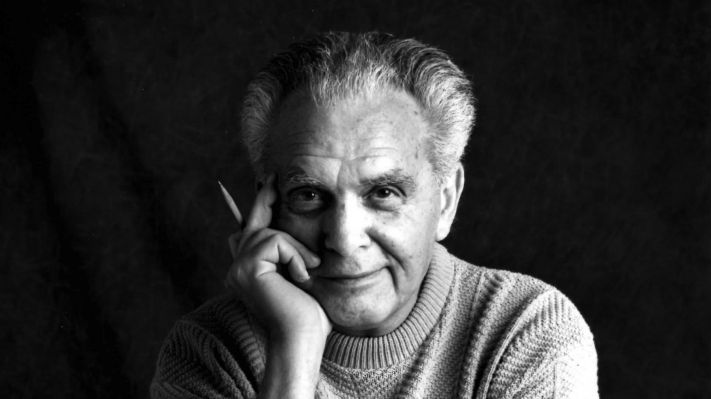

Lee, of course, remains the most famous of the three. Long before he became known for his cameos across the Marvel Cinematic Universe, he was the face of Marvel Comics, giving talks and interviews, writing chatty editorials about the Marvel Bullpen — ’nuff said. It was in those editorials that Kirby was given the nickname that he’s still remembered for today: The King of Comics.

As Mark Evanier explains in Kirby: King of Comics, the alliterative nickname wasn’t meant entirely seriously. In fact, for a long time, Kirby was embarrassed by it.

“Eventually, so many are calling him ‘King’ that he comes to accept it,” Evanier writes. But even then, “The nickname was only meant by Jack or accepted by him if it came with a twinkle. Always with a twinkle.”

After all, calling someone the King of Comics risks shortchanging the role that so many other writers, artists and editors played in creating the comic book industry and exploring the medium’s possibilities. And yet, just as Elvis remains the King of Rock and Roll, it’s an inarguable fact: Jack Kirby was the King of Comics.

His work with Lee in the ’60s redefined what comics could do. Sure, it primarily trafficked in the language of superheroes, but Marvel characters of the era grappled with far more than spandex supervillains. The Fantastic Four squabbled among themselves like family in between journeys to distant interstellar locales. The X-Men, created at the height of the Civil Rights movement, proved a powerful allegory for equality. Three years later, the Black Panther would hit the scene in Fantastic Four #52, marking the debut of the first mainstream black superhero.

Over decades in the industry, Kirby was never afraid to break new ground, tackle difficult topics or punch out the occasional Nazi. His extraordinary run at Marvel was just one peak in a long career.

And while Ditko and Lee are remembered primarily for their ’60s work, Kirby continued to transform the industry after he left Marvel for its main competitor, DC, in 1970. He broke new ground with four interconnected titles — Superman’s Pal Jimmy Olsen, The Forever People, The New Gods and Mister Miracle — now known collectively as Kirby’s Fourth World. Together, they tell the story of a cosmic war between the planets New Genesis and Apokolips, with the warrior Orion battling the forces of Darkseid, ruler of Apokolips and Orion’s secret father.

The comics were written, drawn and edited by Kirby, and they were bursting with creativity, introducing new characters and concepts in nearly every issue. (Anthony’s first tattoo was inspired by one of these concepts — specifically, the alien computer known as the Mother Box.) And while this was decades before trade paperbacks collecting longer storylines became common, Kirby treated the Fourth World as a single, ongoing epic, making it even more crushing when DC canceled the titles mid-story.

Even then, he soldiered on, creating more memorable comics for DC (including the post-apocalyptic adventures of Kamandi, The Last Boy on Earth) and Marvel (where his 2001 series was even crazier than the original film). He also worked for Hollywood, and did production designs for an adaptation of Roger Zelazny’s Lord of Light — the movie was never made, but the art was ultimately used as part of the CIA operation depicted in Argo. In his final years, he became a symbol of the creator’s rights movement in comics, as he fought with Marvel to regain his original art. (A more recent legal dispute ended with Marvel settling with Kirby’s heirs.)

And years after the Fourth World’s cancellation, he was able to complete the story in The Hunger Dogs. A single graphic novel didn’t provide enough space to wrap up the epic story in completely satisfying fashion, but at least it gave Orion and Darkseid an ending, one that makes Kirby’s anti-war message even clearer.

Paul Levitz was one of the DC executives who brought Kirby back to finish the story. He’s gone on to write books about comics and comics history, and this week, he told us:

Jack Kirby’s distinctive vision of action and combat is at the heart of three media today — not just the comics (to which he also contributed an army of imaginative characters) but film and video games. He took his youthful fights in the slums of NY, his battles with Nazi armies and forged them into a visual vocabulary that defines so many forms of drama. No one in comics ever had a more fertile creativity, more courage as a creator, or greater influence over the process of artistic creation.

Kirby would have turned 100 on August 28. It may seem a little strange for us to be celebrating him just a few weeks after worrying that comics publishers are becoming little more than IP factories for Hollywood. After all, if DC and Marvel have become IP factories, then it was Kirby who laid the factories’ foundation.

For us, though, the point was less about painting Hollywood as a villain and more about insisting that comics have a unique magic of their own.

Kirby’s work may be the clearest demonstration of that magic. Studios have poured hundreds of millions of dollars to bring his cosmic creations to life. Yet for our money, not one superhero movie has completely captured the excitement of Kirby’s best splash pages — of seeing Thor and his companions galloping across the Rainbow Bridge, or Orion and Lightray bursting from the wreckage of a flaming boat, or the Silver Surfer taking a desperate stand against his former master, the planet-eating Galactus.

Maybe in another 100 years, special effects will finally catch up with Kirby’s genius. But we wouldn’t bet on it. And even then, as we do today, we’ll still need heroes to help keep Nazis in line.