Like a pitch drop in the dead of winter, the U.S. Government is slow when it comes to recognizing and regulating emerging technologies. But as the years have gone by, we have largely managed to adapt to the dangers of our own advancement — nuclear weapons, bioengineering, cyberwarfare and the Juicero to name a few.

Ready and waiting at an arms reach from the government, the Research and Development Corporation (RAND) has helped the U.S. think through some of the toughest scientific and regulatory challenges since the 1940s. This year, the think tank is opening its first office in the San Francisco Bay Area. It’s positioning itself to weigh in on some of Silicon Valley’s largest research projects, like autonomous vehicles, drones, AI, cybersecurity and telemedicine.

But unlike the RAND of the past, this new version embodies the scrappiness of startup culture. Formally based out of a WeWork space, office director Nidhi Kalra and the rest of her SF team largely work decentralized from homes and coffee shops around the Bay Area.

The team of a dozen researchers is here to study the development of new technologies and the way in which state and local authorities are working side-by-side with startups to keep everyone safe without sundering innovation.

In the thick of the Cold War

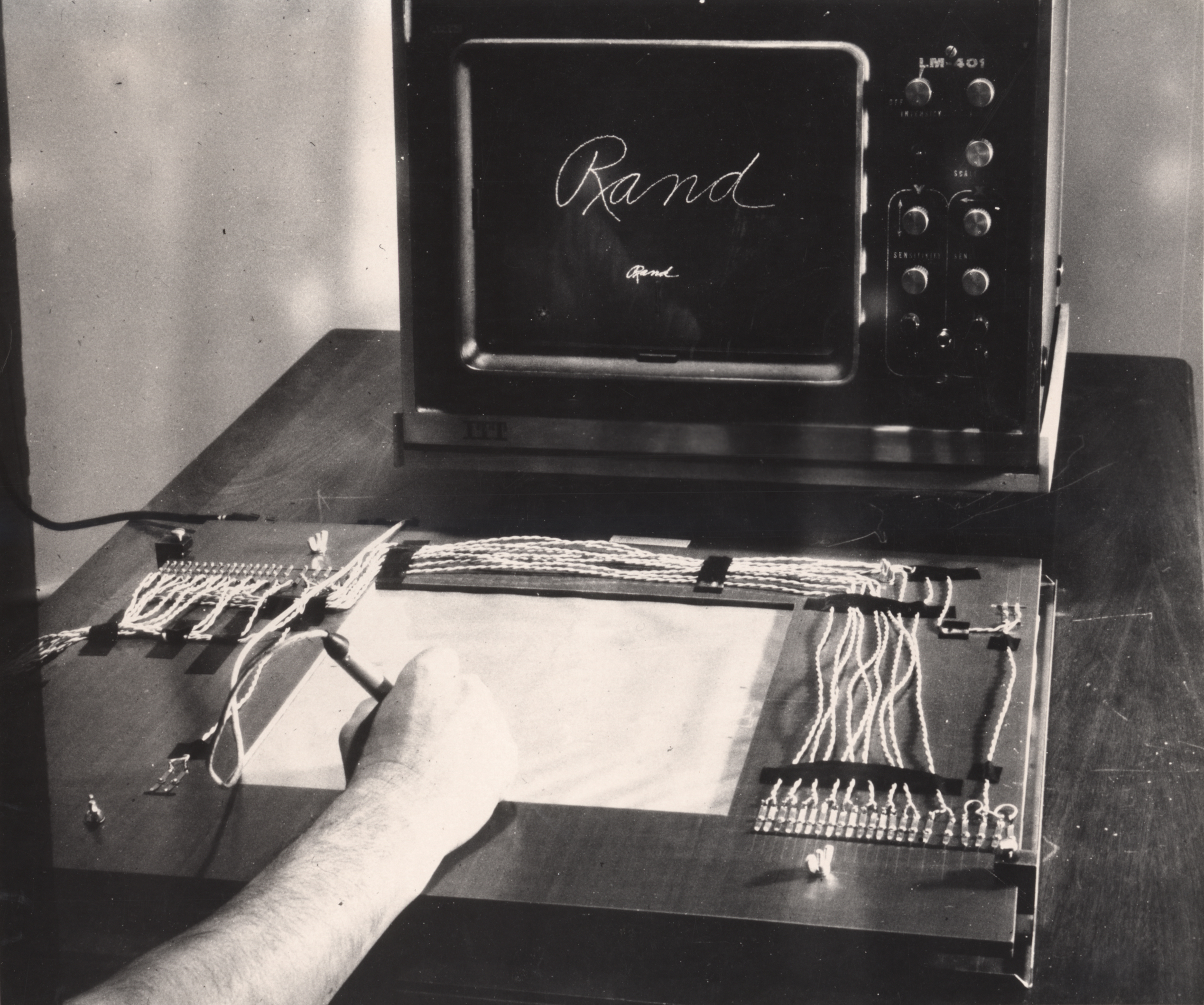

Despite just opening its SF office, RAND has been well acquainted with computing, AI and cybersecurity for decades. One of the earliest computers was built at RAND based off an early design by John von Neumann. The JOHNNIAC, named in von Neumann’s honor, was one of the first computers that did away with punch cards in favor of stored programs.

Just like Google’s X and Facebook’s Building 8 of today, RAND’s flashy computing achievements, like JOHNNIAC, helped it attract top researchers to serve as consultants. John Nash, Allen Newell, Herb Simon and John von Neumann all consulted for RAND at some point during their lives.

Over the course of four decades, RAND and its geniuses helped the U.S. government come up with frameworks for many strategic plays made during the Cold War. We can thank RAND for developing the underpinnings of nuclear deterrence, the intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and space-based photographic surveillance. Even some of the earliest attempts at natural language processing were driven by a desire to automatically translate Russian military communications — that work landed the group its nickname: The Wizards of Armageddon.

But today, RAND is helping the United States government deal with a new set of challenges — challenges of our own creation. As Silicon Valley’s ambition grows and autonomous cars, drones and biohacking inch closer to reality, someone needs to step in to keep tech from falling over the edge and accidentally embracing its internal mad scientist.

The RAND tablet, a graphical computer input device developed at the RAND Corporation in the 1960s. The tablet featured a 10-inch by 10-inch active tablet area and is believed to be the first such graphic device that is digital and relatively low-cost.

The Wizards of Armageddon come to the Bay Area

The tech industry is as afraid of regulators as regulators are afraid of dystopian general artificial intelligence. Neither group understands each other, so we end up with Uber’s insane Greyball system to dodge local police and draconian and ill-informed statements from President Trump calling for parts of the internet to be closed.

To make any headway, RAND understands that it has to study how California and other state and local regulators have dealt with the rapid emergence of new technologies. This means getting on the ground and holding non-confrontational dialog with all stakeholders.

“Increasingly policymaking is happening outside of Washington,” Kalra explained to me in an interview. “Laws are still being passed in Washington but increasingly lots are originating out here in California.”

Unfortunately, influencing the tech industry to make better decisions is a tougher prospect. As a nonprofit entity, it’s difficult for RAND to engage in contracts with private companies like Facebook or Airbnb. RAND can study how short-term rentals are impacting gentrification and socioeconomic stratification and issue a report with best practices for cities, but it cannot force Airbnb to take action or even force the company to hand over its data for analysis.

“We meet with tech decision makers and talk about changes to the H-1B visa program, their ability to hire new talent, how they address income inequality,” added Kalra.

The think tank told me that big companies do tend to have the patience to listen and engage, but their desire to control their own data often acts as a point of tension. Broadly speaking, innovation and policy are at odds, but smart CEOs and entrepreneurs see policy as a catalyst rather than an inhibitor.

“I’ve spent a lot of time at startups and accelerators talking with founders and they have very little bandwidth to consider what we are doing,” Bill Welser, director of the Engineering and Applied Sciences Research Department at RAND, said in an interview. “They have to make their ideas work now or they’re never going to make them work. They don’t think they need to think about the broader contextual space. The thing they are missing, and the reason they’re not exiting the way they might dream, is that they’re missing the context.”

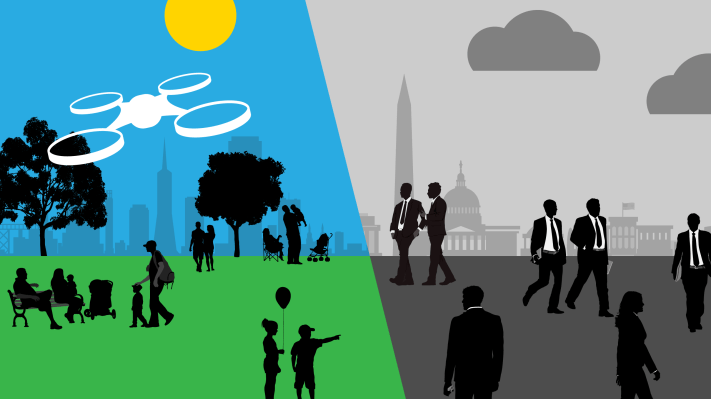

Autonomous vehicle event put on by the RAND Institute for Civil Justice at O’Melveny & Myers’ San Francisco office.

Most of these conversations happen at invitation-only closed-door events, which is great for getting leaders to talk candidly, but not great for brand recognition. Most folks today wouldn’t know if you were talking about Ayn Rand or Rand Paul if you mentioned RAND in conversation — and that’s unfortunate.

RAND is one of the few government-funded entities that will entertain a discussion about topics like universal basic income. The team aims to think bigger than Washington without losing an understanding of the centuries of American history that led us to where we are today.

“I’m interested in what keeps [founders and CEOs] up at night, outside of [their] own business bottom line,” Kalra asserted. “What are the challenges facing our world that you think an org like RAND should be paying attention to.”

Increasingly policymaking is happening outside of Washington. Nidhi Kalra Director, San Francisco Bay Area Office

Today, RAND is concerned with interpretability in AI systems. If AI is ever going to inform policy decisions, there needs to be accountability. This is perhaps one place, among many, where RAND can stand on the shoulders of giants at AI research groups like Google’s DeepMind and Facebook’s FAIR to learn better ways of applying machine learning models to craft policy.

Kalra explained to me that she is not just interested in the way technology directly impacts the world, but the second and third order effects that technology creates — think the growth of suburbs after the democratization of the automobile. And as much as the Bay Area is a hotbed for cutting-edge engineering, it also is a hotbed for social issues — homelessness and gentrification in San Francisco, the ongoing affordable housing crisis and neighborhood juxtapositions like Palo Alto and East Palo Alto.

The new Bay Area office might not be a salve to these problems, but it is clear that Washington is listening and paying attention — whether the Valley meaningfully engages in return is yet to be seen. But one thing is clear, the real regulatory battles that will decide the next phase of America’s relationship with emerging technology will occur in unsexy boardrooms — the public spectacle of techies disrupting D.C. will mostly fall on deaf ears.