Carnegie Mellon robotics spinoff HuMoTech (short for Human Motion Technologies) hasn’t actually spun too far yet. When we paid a visit to the prosthetic leg developer’s office last month, the startup was still crammed into a single basement room on the University’s Pittsburgh campus. The company’s founder and CEO Josh Caputo assures us that it’s about to move to larger digs, but for now the setting is exactly what you’d expect from a scrappy hardware startup.

There are white boards lining the walls covered in complex formulas and earlier iterations of the company’s robotic leg are scattered in pieces on and underneath tables. You can practically chart the company’s half-decade of development with a quick look around the room, from Caputo’s 2010 PhD work on robotic feet to its first product offerings: a pair of devices designed to help clinicians better fit amputees for prostheses.

The space is made even more cramped by the giant treadmill monopolizing the middle third of the room. It’s HuMoTech’s testing bed, now occupied by Tony Stader, a local with a missing right leg who has volunteered his time to helping the startup get off the ground. He’s also become something of a makeshift model for the company’s service. It’s his smiling face you see gracing the product demos all over its website.

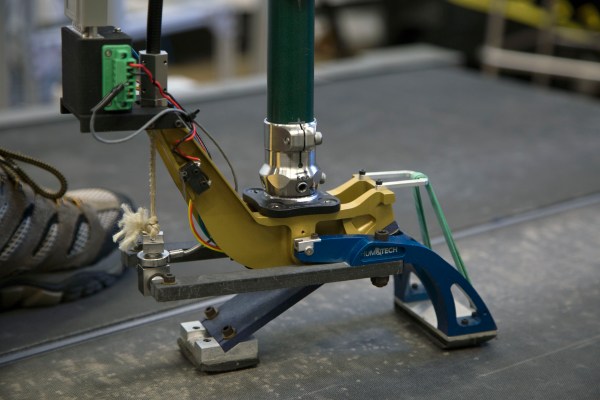

Stader is already hooked up and wired in when we arrive, with the ankle prosthesis connected to the socket on his right leg. The system is clearly not designed to disguise the fact that it’s a prosthetic. It’s fairly skeletal and minimalist. A single rod extends to an actuated base that more closely resembles a metal arch than a human foot. The whole thing is tethered by a series of wires that extend off the back, connected to an actuation unit that spins back and forth as he walks.

Behind the treadmill, head Software Engineer Richard Ha (who represents half the company’s engineering team and one-third of the entire staff) sits behind a large computer, reading the feedback outputted by the system during Tony’s brisk workout. Beyond just numbers, the setup is also capable of emulating a wide range of prosthetics, mimicking different properties like flexibility and strength.

“There are hundreds of different products on the market,” says Caputo. “It’s surprisingly complicated. And clinicians have to make decisions about what products to give to their patients, mostly based on their intuition that’s developed over the years. They have little in the way of established processes or scientific literature to look at to guide them in their decision making process.”

It’s a tricky task, in part because people are, themselves, complex systems, so there are a lot of variables in introducing a new element like a prosthetic. “The human body, walking, the whole neural control system is so complicated, we’re only beginning to understand it,” Caputo adds. “It’s difficult to design an advanced machine that interfaces with this complex system, the human body, which we don’t understand very deeply.”

The emulation gives patients an opportunity to see how different systems fit, without having immediate access to the actual prosthetics. It could well prove an important tool given the fact that, once a prosthetic is chosen for a patient, they’ll have to live with the device every day for a long time. Even non-robotic prosthetics can be extremely pricey and often times difficult to return. The system also helps lend an objectivity to the decision making process by presenting different prosthetics in a blind testing scenario.

After Stader finishes his demo, Caputo brings our attention a series of cabinets lining one of the room’s walls. Like much the rest of the cramped room, the tops of the metal units have been turned into a makeshift storage space, housing a bizarre collection of leg braces and platform shoes. He pulls one of each down off the top. They’re holdovers from HuMoTech’s earliest days, when Caputo had to test the system himself.

“Since I’m not an amputee, I can’t just put the prosthesis on as it’s meant to be used,” he explains, before slipping them on. “So I wear an immobilization boot that’s normally used to help heal ankle fractures, and I mount the prosthesis under there. Because my leg is so much longer than the other, I wear this lift shoe on the other side.”

It’s an awkward solution, and one that highlights both how far the company has come in the last seven years, and how far it has left to go, as Caputo still dons the system when Stader or another volunteer isn’t readily available to help out.

When he is volunteering, Stader serves as a reminder of why getting the right fit is so important. “When you originally come out of the hospital, they give you the standard, and it’s pretty awful,” he explains. “I have two small sons that are 10 and 7. They’re both in little league baseball. And when they’re home, it’s game on.”