For such a simple tool, the white cane has been incredibly enduring. With all of the technological advances that have been made over the past century, we haven’t come up with much better than a stick with a metal tip for helping the visually impaired get around. Though researchers at MIT have been working on a wearable solution designed to augment and, hopefully, one day replace the cane.

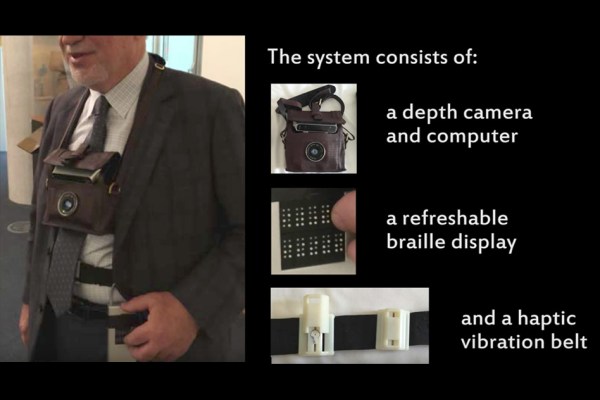

The system features a 3D camera with an on-board computer hung around the neck at chest level. The camera senses the location of objects, converting the signals into pulsing haptic vibrations that alert the wearer to the location of an object. The on-board motors vibrate with a variety of patterns and frequencies to signify different things, like the distance of an object.

The team says the abdomen is the ideal spot for the vibrating belt, because it has the right amount of sensitivity, but doesn’t interfere with other senses. Audio indications were ruled out in early testing, as visually impaired people tend to rely very heavily on their hearing. And buzzing around the head and neck, understandably, just would have been too distracting.

The system also uses object recognition and braille pads to identify specific objects — popping up, say, a “t” for “table” or “c” for “chair.” It also is able to understand and relay distinctions well beyond what the simple cane is capable of, like whether or not the chair in question is occupied.

“The system can assist the user to do tasks well beyond what a white cane can do,” Daniela Rus, the head of MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) tells TechCrunch. “Like finding a chair in a hotel lobby and understanding whether it is empty or not. We take this kind of task for granted — but just close your eyes and imagine how you would find an empty chair in a crowded space with the use of a white cane that gives you only point information about the world.”

The team has been testing the system on visually impaired subjects around its labs to good effect. With the chair-finding test, the system is able to reduce accidental contact by 80 percent. When the subjects were asked to navigate around the MIT halls, collisions with people hanging around the hallway were reduced by 86 percent.

It’s still pretty early stages. The team has only used the system with about 10 volunteers at the moment, so a lot more testing is needed if it’s ever going to become a viable option for sight-impaired people. And it will be even longer before it means people can throw away the cane. Though Rus is hopeful that it will some day lead to something commercially viable.

“In a world where computers help us with everything from navigating space travel to counting the steps we take in a day, I think we can do better to support visually impaired people than a walking stick,” says Rus. “Not by retrofitting something we’ve already designed, or looking for ways to use current applications in novel ways, but by working with the visually impaired to understand how computers can augment their capabilities, become an extra set of eyes in a way, and then developing technology with the expressed purpose of fulfilling that goal.”