There’s no shortage of ways adversaries will employ to get you to click through to a malicious website, some technical, some psychological. This one is interesting because it leverages a useful feature of browsers that you might have never thought about.

Not all websites have names that can be written in the alphabet we that primarily English-speaking countries are familiar with. Why shouldn’t Russian websites use Cyrillic characters, or Japanese ones use kanji? After all, Unicode, the standard for displaying text worldwide, supports all these languages.

Unfortunately, it’s not standard to allow all those characters in URIs, and some systems only allow standard ASCII ones. The workaround arrived at by web authorities was a system called “punycode” that encodes international characters using ASCII notation. Browsers will know a URI is using the system because it’s always preceded by the characters “xn--“.

The whole process is done without informing the user; so “JP納豆.例.jp” becomes “xn--jp-cd2fp15c.xn--fsq.jp” in transit, but you never see the unintelligible latter one, only the former, rendered in its intended language.

That transparency, the fact that punycode doesn’t announce it’s being used, is the basis for the phishing attack. An attacker can use punycode to create URIs that look normal to the user but are actually totally different. Pedro Umbolino over at Hackaday showed how this is possible in a post that certainly had me fooled.

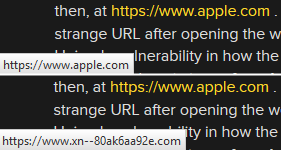

Several browsers, including Firefox and Chrome, rendered the link in the first paragraph as what appeared to be apple.com, both inline and in the link preview. But when you click, it goes somewhere totally different.

In fact, as you find out later in the paragraph or if you change the settings in your browser, the letters in apple.com are actually created by the punycode xn--80ak6aa92e.

That forms something that looks like apple.com the way browsers render the text, but if you look at the URI in certain monotype fonts, it’s clear there’s a classic capital-“I”/lowercase-“L” switcheroo, with a Cyrillic twist:

That forms something that looks like apple.com the way browsers render the text, but if you look at the URI in certain monotype fonts, it’s clear there’s a classic capital-“I”/lowercase-“L” switcheroo, with a Cyrillic twist:

![]() Clever, right? A hacker could use this in an email or another link to lure even a normally attentive user who inspects suspicious links. As Umbolino shows (and this is a separate issue) the site you’re tricked into visiting may even imitate the real site’s HTTPS status, giving you that reassuring green lock next to the URI.

Clever, right? A hacker could use this in an email or another link to lure even a normally attentive user who inspects suspicious links. As Umbolino shows (and this is a separate issue) the site you’re tricked into visiting may even imitate the real site’s HTTPS status, giving you that reassuring green lock next to the URI.

Yes Devin, but how do I fix it

Firefox and Chrome were the only browsers affected, really — it just had to to with the defaults they had for displaying punycode stuff. But Chrome 58 (just out) makes those addresses show the full punycode URI in the link preview, and Firefox has a setting that changes it. Just go to about:config, put “punycode” in the search there, and toggle the setting that comes up to “true.” You’ll see the xn-- punycode links from now on — but remember, most are legit! Just be aware of when you should expect one and when it could be shady.

You learn something new every day! Well, sometimes.