Keeping a forest healthy often means deciding what to do tree by tree and acre by acre. That’s easy enough with a square mile of it, but what about a thousand? The Nature Conservancy is working on tools that will make it easy for park services, fire control and conservationists to keep entire forests alive, thriving and — you know, not on fire.

Forest management is a complicated industry, but for our purposes what matters is that this part is done in a pretty old-school way.

One approach has someone walking through the forest, scoping things out, and using a can of spray paint to designate certain trees one by one to be cut down or left behind. Nice to have a personal touch, but not exactly quick to execute.

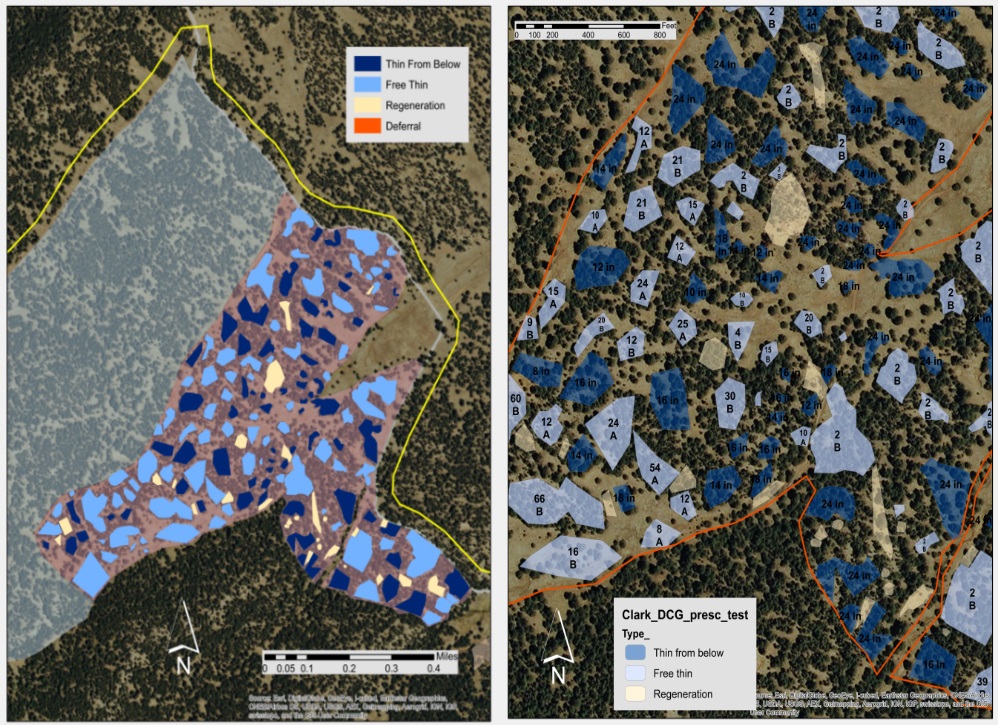

Another has an expert marking up a map with “prescriptions” for each area: what types of trees to cut, what to leave, etc. But not only does this lack the detail of the previous approach, but the loggers who are to cut the trees will move more slowly as they rely on their discretion to determine what fits the prescription’s bill, or argue over which zone they’re in.

Here’s a situation where technology actually can come to the rescue. Neil Chapman at Nature Conservancy is leading a project that aims to make this part of forestry simpler, cheaper and faster. And with the devastation caused by wildfires recently, it’s not merely a question of healthy forests any more, but of preventing serious disasters.

Cutting delays

“Northern Arizona is home to the largest continuous Ponderosa pine forest in the country, and we’ve had a million acres of it burn up in catastrophic wildfires over the last 15 years,” said Chapman in an interview with TechCrunch.

“Forestry practices need to be scaled up to deal with the problem. But they do not have the time or the money to be painting the trees on 50,000 acres a year. So we said, there has to be something we can design that will let forestry increase that pace, while still relying on boots on the ground.”

The resulting Digital Restoration Guide combines the directness of painting with the scalability of prescription.

Essentially, a forestry worker will walk (or ATV) around as before observing the forest directly. “But instead of having a paint can, they have a tablet in their hands,” said Chapman.

They can note the locations of individual trees or groups of them with GPS coordinates, but they don’t need to tag every one. Instead, after getting the gist of an area, they can make a little polygon on the tablet’s map that has all the details.

This data can be adjusted after the fact, archived and sent to harvesters, who can consult it from an in-cab tablet. (You can see the app in the image at top.)

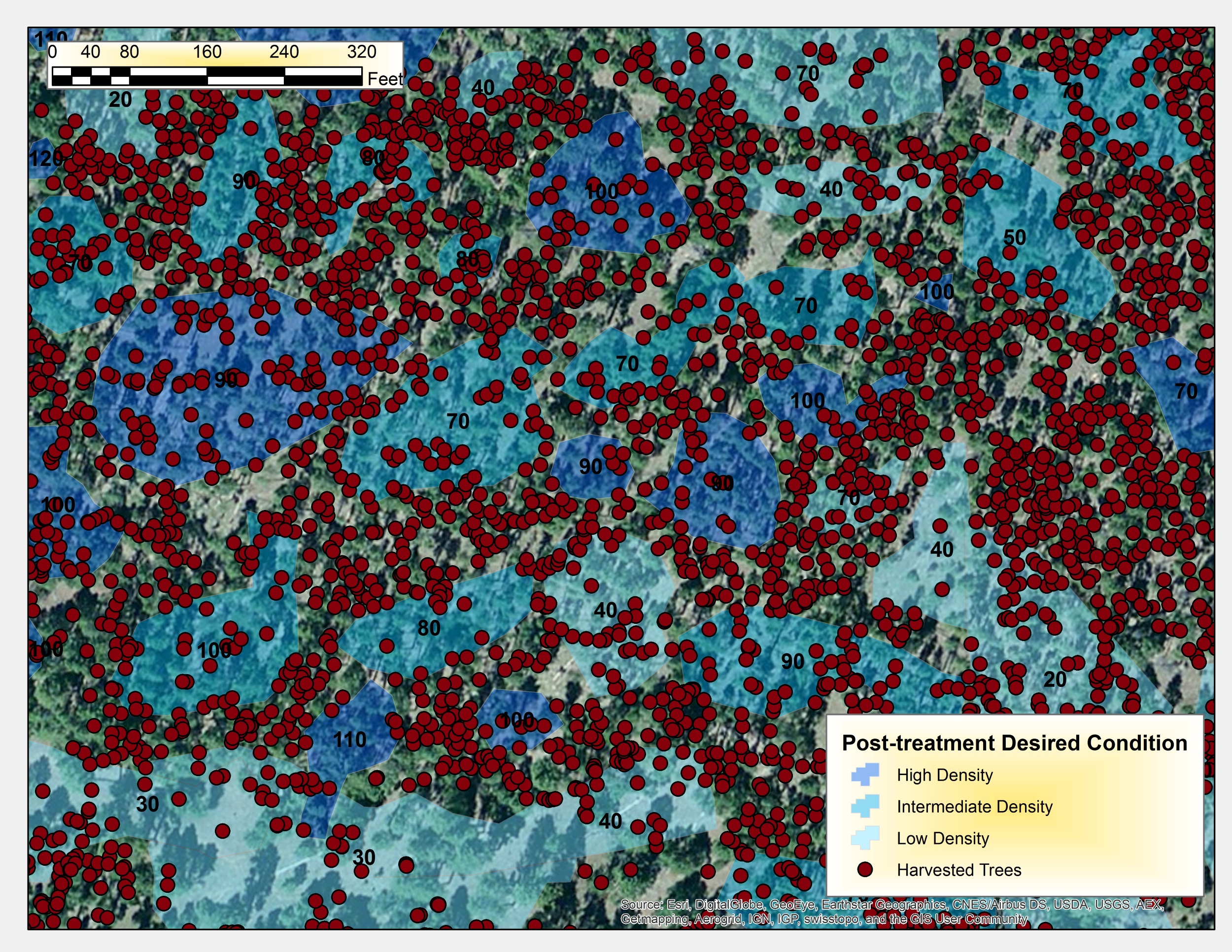

Not only are they given more specific instructions and better granularity, but the tablet will also record the exact location, time and diameter (among other things) of felled trees. This saves time on the back end — much less paperwork — and lets harvesters track progress more easily, to boot.

Not only are they given more specific instructions and better granularity, but the tablet will also record the exact location, time and diameter (among other things) of felled trees. This saves time on the back end — much less paperwork — and lets harvesters track progress more easily, to boot.

This is important, Chapman said, because the forestry service has more complex guidelines regarding restoration and harvesting, more so than city or county authorities, which have comparatively small and homogeneous forests to manage.

Tech among the trees

A pilot deployment on 327 acres found that, compared with painting trees directly, the digital prescription method cost less than half as much and was five or six times faster. Productivity was similar to the old prescription methods, which Chapman portrayed as a victory.

“If in these early stages we can keep up with DxP on city and state land… Forestry is much more demanding,” he said, something that plays to digital prescription’s strengths. And that isn’t even taking into account the considerable benefits of the workflow in tracking and ease of use.

“After the markers go through, our staff is able to calculate the size, interspace, tree numbers… in the past they used to have to go out and take samples.”

“After the markers go through, our staff is able to calculate the size, interspace, tree numbers… in the past they used to have to go out and take samples.”

They have had to modify the interface and hardware in response to feedback, for instance upping the power of the tablets.

“It turned out some of the maps were pushing the limit of the processor speed on the tablets we were using. Loggers were zooming in and out of a 300-megabyte image and it wasn’t going fast enough,” Chapman said. “It’s better now. I mean, you can’t be sitting there in your cab waiting for an image to render.”

Lidar and drones, perennial favorites when it comes to crossing over between the digital and real worlds, are also in play.

[gallery ids="1478447,1478446,1478445"]

“We’ve been looking into how to use lidar for the planning and monitoring stages,” he said. “Normally we’d have to go out and do time-consuming ground truthing. Using lidar or structure from motion [another 3D imaging technique], if we have images of 50,000 acres, then images after we cut those acres, we don’t need to go out there and use ground data.”

Fixed-wing and multirotor UAVs are in the mix, the former for larger surveying missions and the latter for monitoring smaller areas and rapid ground truth.

The pilot studies impressed the Forest Service enough that the tech has been okayed for use on 5,000 acres in the Coconino National Forest and 3,800 acres in Kaibab National forest; it’s part of the ongoing Four Forest Restoration Initiative. The former has already been mapped and the test will be the deployment of the enhanced harvesting teams to the areas designated using the new tools.

If this catches on, and it really ought to, it could drastically improve the efficiency of the rangers and loggers who care for our forests. You can follow the project’s progress over at Nature Conservancy’s site, or at Arizona’s 4FRI page.