A picture is worth a thousand words… that no one wants to type on a tiny screen. And even if you did mash in all that text, it’d still lose the subtleties of sarcasm or sincerity. To express the full range of emotion, messaging apps must put us face-to-face despite our distance.

“We like to think of the camera as the new keyboard,” Facebook Messenger product manager Tony Leach tells me. So nine months ago, his team embarked on an ambitious project to redefine the billion-user chat app as a way to share images, not just words.

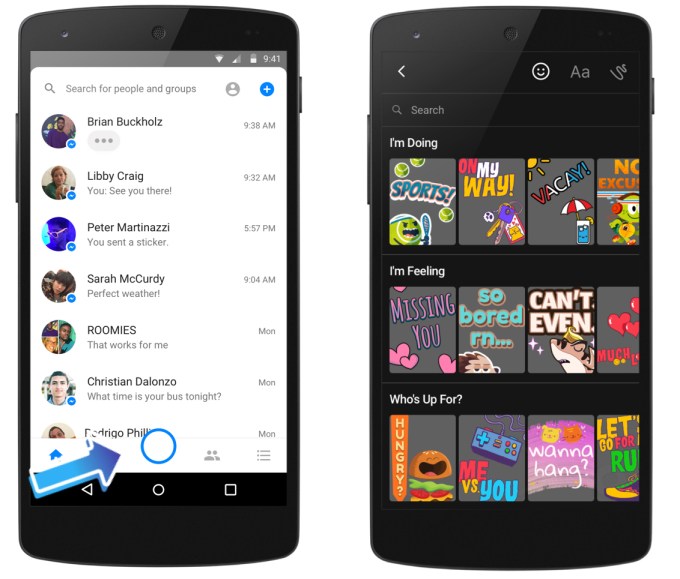

That’s manifested as a shutter button on the Messenger home screen, more than 5,000 graphical filters and stickers you can add to photos and videos and computer-generated art that turns any text into an overlaid illustration. Messenger even has its own Stories feature called Messenger Day, which, while currently only available in a few countries, is slated to roll out wider soon, including in the U.S. [Update: Messenger Day is now rolling out worldwide. For how it works, check out our story here]

Messenger Day and that “camera as keyboard” quote should be very familiar. The feature is another interpretation of the Stories slideshow format Snapchat pioneered. And in Snap’s IPO filing, it described its philosophy, saying, “In the way that the flashing cursor became the starting point for most products on desktop computers, we believe that the camera screen will be the starting point for most products on smartphones.”

But just as we don’t still call every algorithmically sorted feed a Facebook copycat, nor every chat service an ICQ clone, visual communication is bigger than just Snapchat. No matter who popularized it, any messaging app that doesn’t embrace the concept is doomed.

“Gradually, as communications become more visual, we had to build a camera that’s more powerful,” says Facebook’s head of Messenger David Marcus.

Getting visual, pixel by pixel

Messenger first dipped its toes into the world of visual communication with the addition of Stickers in 2013. At the time, the company was actually reluctant to build the feature, according to a source familiar with the development process. Facebook’s leadership assumed Stickers were just a silly toy for kids and their popularity in Asia wouldn’t translate to the West.

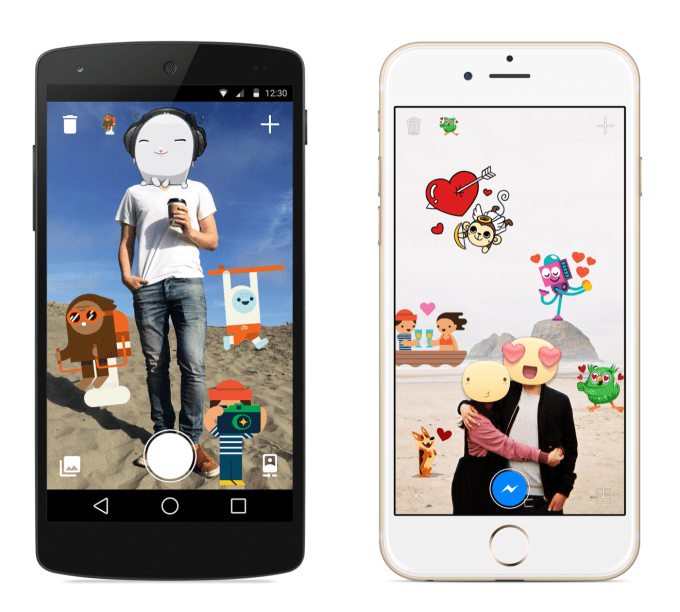

Facebook’s Stickered app

Surprise! Stickers were a hit. But they only appeared on the blank white background of your messaging threads. By 2014, Snapchat had proven the popularity of overlaying text, emoji and drawing atop photos and videos. This collage style allowed people to not only show how they felt or what they were doing, but embellish and riff on it. Combining images, text and symbols let people deliver a vivid yet nuanced idea instantly, opening up new opportunities for comedy.

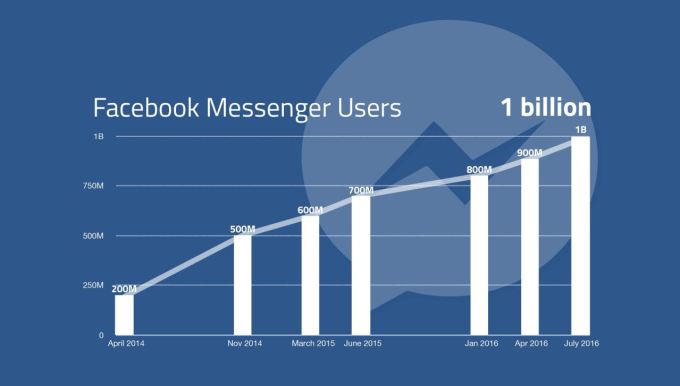

It was then in mid-2014 that Facebook got serious about the business of cloning. It launched an overly complicated Snapchat clone called Slingshot, added a selfie camera plus text and drawing overlays to Messenger and launched a dedicated standalone app called Stickered for adorning photos. Again, visual communication was a hit. Messenger’s growth spiked, increasing from 200 million to 500 million users in just seven months.

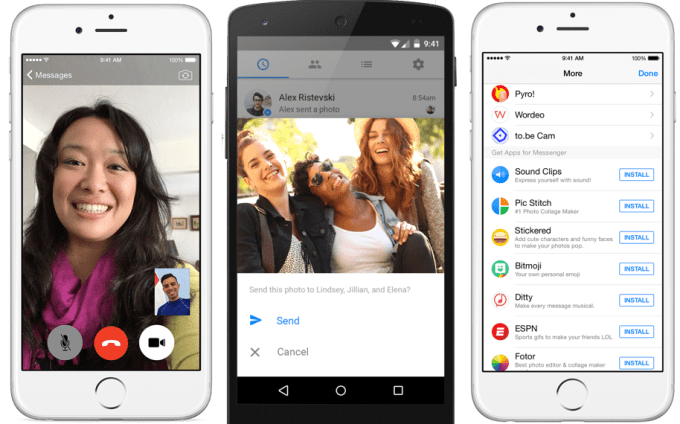

Messenger then finally diverged from the Snapchat playbook in 2015 by launching a developer platform to let you share GIFs, augmented photos and video clips via apps like Giphy, PingTank and ESPN. Facebook realized that not all users are creative enough to dream up their own imagery, so offering ways to pipe them in made visual communication more accessible.

Meanwhile, Messenger simplified photo sharing by using facial recognition to help you send friends your shots of them. And it actually started putting users face-to-face with video calling. Messenger’s meteoric rise continued as it added one hundred million more active users every few months.

Facebook Messenger’s video calling, Photo Magic, and content app platform (from left)

But its cornucopia of visual communications features all felt bolted on and buried within Messenger. They were essentially camera stop-gaps for an app born out of the group text chat era. It wasn’t clear what to do next, and Messenger spent the first half of 2016 mired focusing on chatbots that never quite worked right.

As scary as it would be to move a billion people’s furniture, Facebook needed to fundamentally overhaul its interface to put the camera at the core of Messenger.

Centering the camera

“The camera is a great way to initiate a conversation or share a moment that you want people to comment on,” Marcus tells me. That’s why it couldn’t be tucked away inside of chat threads. When you send text messages, you typically think of who you’re going to talk to first. But with visual communication, it’s the spontaneous moment you want to capture or the silly face you want to make that sparks the sharing process.

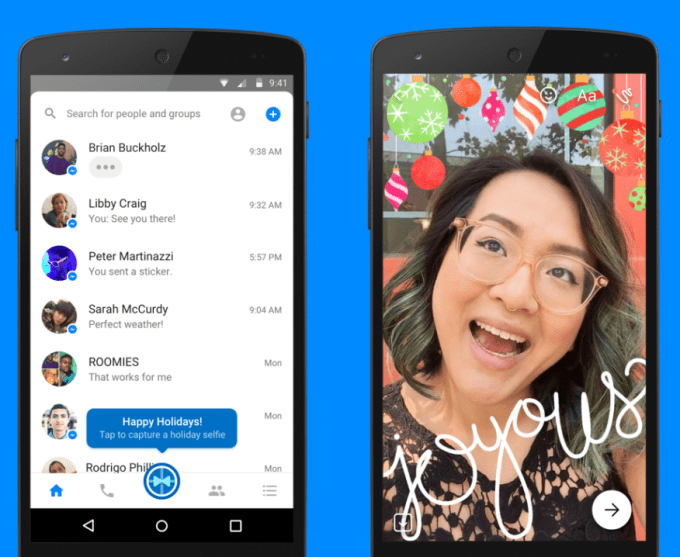

So in mid-December, Messenger launched its big redesign. The top corners of the inbox became rounded to clue users into the idea that they were always a swipe away from the camera, that now sat beneath the rest of the chrome. And a big transparent shutter button was overlaid in the middle of the navigation bar at the bottom. The camera literally became the center of the app after years in the periphery.

But instead of just porting a stock camera into the app, Marcus tells me, “We’ve done it in a way that is very much in line with the types of things you do with messaging.”

Once you take a photo or video, you can select from more than 5,000 graphics to add on top, and these are themed and categorized around the most popular questions and statements people share in Messenger. There are graphics for “Hungry?”, “Wanna hang?”, “On my way”, “Missing you” and more.

These aren’t the kind of filters you find in Instagram for jazzing up art, or Snapchat for telling a story of what you’ve been doing. They’re designed for the present tense, like illustrated keyboard shortcuts.

This set of graphics is already having an impact in Messenger behavior. “Slowly but surely we’re seeing it used for conversation starters” that lead to more and longer chat sessions, Marcus tells me.

The artwork has been especially successful in prompting message threads around holidays like Valentine’s Day or Australia Day, when Facebook temporarily offers special filters with related iconography. Injecting these surprises keeps users checking back for new ways to share. Snapchat does the same with its rotating set of selfie lenses, but Messenger gives users an extra hint that there’s something to explore. It “gift wraps” the shutter button with the holiday’s theme to signal there are special filters available as soon as you open the app.

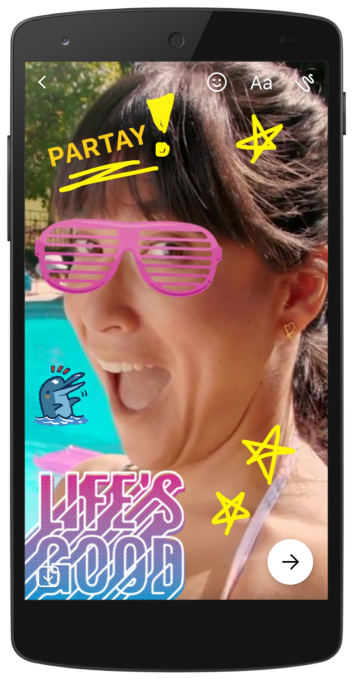

For those who are a bit camera-shy, Messenger integrated Snapchatty selfie masks thanks to Facebook’s acquisition of MSQRD. If you want to jazz up the background of your shots, you can add environmental filters that make your screen a lava lamp or add patterns you can manipulate with the wave of your hand. Messenger’s also got Prisma-esque “style transfer” filters that make your photos or videos look like line drawings or Picasso paintings.

And in case there’s something totally unique you want to say with extra pizzazz, Facebook automatically generates filters based on what you type. You can turn a friend’s name, an inside joke or any phrase you want into an array of overlaid graphics. It’s one way Facebook’s deep bench of artificial intelligence and design talent is paying dividends in unexpected places.

Humanizing the text message

Visuals for the sake of visuals can be fun, but the real test of the Messenger camera is if it can make the boring, everyday logistics conversations less soul-crushing. Anyone who’s ever debated a shopping list or plans for a night out over text knows how it can suck the humanity out of what would be pleasant in person.

Visuals for the sake of visuals can be fun, but the real test of the Messenger camera is if it can make the boring, everyday logistics conversations less soul-crushing. Anyone who’s ever debated a shopping list or plans for a night out over text knows how it can suck the humanity out of what would be pleasant in person.

“I was in the grocery store looking for something my wife had asked me for. I couldn’t remember if it was potato starch or potato flour,” PM Tony Leach recalls. “I just snapped a photo and drew ‘which one do you want?’ She circled the one she wanted and it made the conversation a lot easier.” Instead of getting scolded for forgetting, Leach diffused the situation with visuals. These are the utilitarian use cases Snapchat and Instagram don’t have to worry about.

Today, Messenger’s camera is just for private conversations here in the U.S. However, in Poland and Australia, users can broadcast their visual creations and invitations to hang out via Messenger Day, which creates a slideshow of photos and videos that disappears after 24 hours. Facebook shared with me that Messenger Day will be rolled out to more places soon, including the U.S. On the surface, it might look like just another Facebook clone of Snapchat, like Instagram Stories and Facebook Stories. Yet deep down, it’s based on a camera purpose-built for communication.

If Messenger can make our daily exchanges casual and fun, it could lure users away from its competitors and the status quo of SMS. Facebook must avoid cluttering the app in ways that interfere with its convenience. Sometimes a few quick words is the best way to get an idea across. But as smartphones become conduits of our identities, and messaging emerges as the heart of the mobile experience, our chat apps must flex to encompass every form of expression.