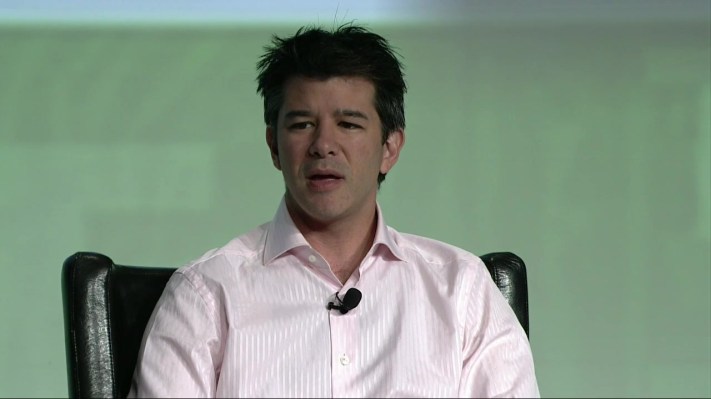

A newly published video clip of Uber CEO Travis Kalanick may offer the world’s first glimpse into his thinking about businesses that compete with his ride-sharing juggernaut.

The clip — filmed earlier this month while Kalanick was using Uber’s Black car service and provided to Bloomberg this afternoon by the driver, Fawzi Kamel — mostly shows Kalanick bantering with the two women between whom he is sitting.

Once Kalanick prepares to exit the car, he shakes Kamel’s hand and engages in a conversation that he presumably thinks will be friendly but quickly sours. In that interaction, Kalanick explains why Uber’s rates have fallen so dramatically, pointing to competition that has made price drops inescapable. Meanwhile, Kamel argues with Kalanick, telling him he could have kept prices higher and that Kalanick’s decision not to do so has “bankrupted” him.

The conversation ends when Uber tells Kamel to take responsibility for his own decisions.

Kalanick has since apologized to his employees for his tone in speaking with Kamel. In an email to them this evening, he writes:

By now I’m sure you’ve seen the video where I treated an Uber driver disrespectfully. To say that I am ashamed is an extreme understatement. My job as your leader is to lead … and that starts with behaving in a way that makes us all proud. That is not what I did, and it cannot be explained away.

It’s clear this video is a reflection of me—and the criticism we’ve received is a stark reminder that I must fundamentally change as a leader and grow up. This is the first time I’ve been willing to admit that I need leadership help and I intend to get it.

I want to profoundly apologize to Fawzi, as well as the driver and rider community, and to the Uber team.

You can check out the full clip below to see what transpires, and why Kalanick might have been caught off guard.

Kalanick initiates the exchange by talking work with Kamel, noting to him that, “We’re reducing the number of Black cars over the next six months. You probably saw the email.”

“I saw the email, starts in May,” Kamel says. But he quickly adds: “It’s all about the rating. But you’re raising the standards but dropping the pricing.”

Kalanick shoots back, “We’re not dropping the price on Black.”

“But in general . . . , ” says Kamel.

“We have to, we have competitors,” says Kalanick. “Otherwise, you go out of business.”

Here, the driver presses Kalanick, saying doesn’t believe the matter is out of Kalanick’s hands. He suggests that Uber could have and should have remained a service for people who would otherwise take private town cars — Uber’s earliest model — rather than a business that features a variety of price points for a variety of riders. “There is, man. You had the business model in your hands. You could have the prices you want, but you choose to give everybody a ride.”

“No,” Kalanick starts,”you misunderstand me. We started high end. We didn’t go low end because we wanted to, we went low end because we had to . . .”

Kamel then seemingly refers to Lyft, calling competition with Uber’s most direct competitor a “piece of cake.”

“No,” says Kalanick. “It seems like a piece of cake because I’ve beaten them. But if I didn’t do the things I did, we would have been beaten . . .”

Kalanick tries to reroute the conversation, offering that “We could do Lux in San Francisco,” Uber’s highest-end service yet, which is already available in a number of other cities in the U.S. “I have guys working on Lux, which will be 50 to 75 percent more expensive than [Uber] Black.”

But the conversation rapidly devolves, with Kamel not satisfied with this answer and instead telling Kalanick that people “don’t trust you anymore,” and adding that Uber has cost him $97,000 and that he’s now “bankrupt” because of Kalanick. “You keep changing every day,” says Kamel.

“Hold on a second. What have I changed about Black?” says Kalanick.

“You changed the whole business. . .You dropped the prices.”

“On Black,” says Kalanick, incredulous.

“Yes, you did.”

“Bullshit,” says Kalanick.

Kamel continues to argue with him. “We started with $20 [per mile]. How much is the mile now? $2.75?” (According to an older version of Uber’s site uncovered by Bloomberg, Uber Black cost riders $4.90 per mile in 2012 and $1.25 per minute in San Francisco; today, Uber charges $3.75 per mile and $0.65 per minute.)

At this point, Kalanick’s patience is at an end. As he opens the door and begins to exit from the car, he testily tells Kamel: “You know what? Some people don’t like to take responsibility for their own shit. They blame everything in their life on somebody else.”

He then exits, wishing Kamel, “Good luck.” Frustrated, Kamel replies: “Good luck to you to, but I know you [aren’t] going to go far.”

It’s neither a pretty nor surprising exchange. It does show the tough position that Uber finds itself in, though, both financially and with drivers who’ve grown frustrated by rates that make it harder to make a living.

Early Uber investor and board member Bill Gurley talked last September with Recode about his concerns about Uber’s competitors and the impact that they’ve had — and will continue to have — on the company’s bottom line.

“I don’t think that we’re going to be going public any time in the near future,” Gurley said at the time of Uber. “We have a large number of competitors who are very deep-pocketed, who have decided that their primary form of competition is just price. There are intense subsidy battles going on all over world. Those companies, when they approach investors, tell them, ‘Uber’s going to go public, and then they’re going to have to be profitable, and then we’re really going to sneak up on them with these discounts.’”