Immigration into the U.S. is a hot political topic right now, but, unless you’re Native American, pretty much everyone here has a family history involving some sort of immigration story.

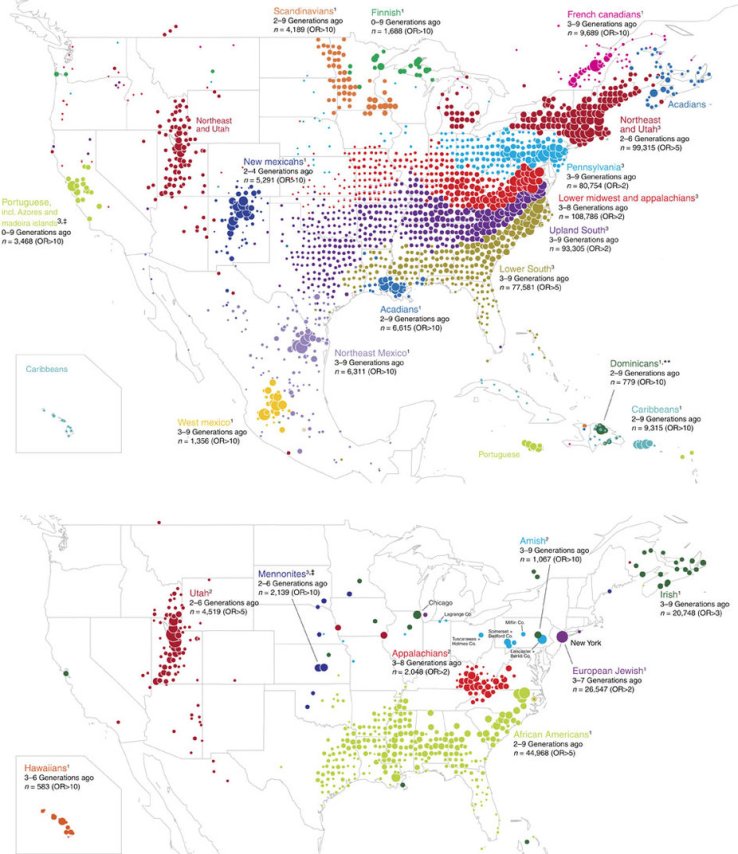

Now AncestryDNA, a consumer genetics subsidiary of the genealogy research site Ancestry.com, wants to help you know more about your family’s immigration journey. To do so, the research team spooled through 500 million points of genetic data, then connected the genetic dots for 770,000 genotyped individuals from the U.S. and linked them up with 20 million genealogical records and collective migration patterns in North America during the last several hundred years — so, a LOT of data.

And what they found was pretty interesting — many networks of families have followed each other, intermarrying and settling near one another for centuries

For instance, there’s a good vein of Louisianian’s of French descent with cousins in Maine, a cluster of New Englanders headed West to Utah and there are even trace genetic differences in Irish Americans who settled in the Northern versus Southern states, divvied up right along political lines.

These genetic differences can be based on any number of factors such as war, disease, climate change or religion. And it’s been happening throughout much of human history. In Europe, for instance, people were divided by Catholic versus Protestant or by nobility versus peasants.

Similar patterns have also painted our American history. The Amish, for instance, are a geographically isolated subset of German immigrants. You can see distinct genetic markers within this American community versus other Americans of German descent.

Other communities, such as certain parts of Maryland, can trace their African American roots back to a handful of families who left rural areas for better jobs in the city. Friends and family members would hear of how good the prospects were and move their family as well.

The information could be particularly helpful to African Americans. Those seeking to connect themselves to an ancestral paper trail often get stuck due to earlier slavery practices in the United States. But, says head of the project Catherine Ball, AncestryDNA has been working hard at coming up with ethnicity estimates to help these communities.

Genetic information is usually harder to get if you aren’t of European origin and most of the consumer-facing genetics companies utilize very small sets of data for other ethnicities, making it hard to determine the accuracy of that information. But if you can connect genetic communities you may be able to find all sorts of other valuable information linking you to your past.

The work, which was highlighted this month in the scientific publication Nature Communications, is only in the pilot phase at the moment, says Ball. Though she did hint the consumer-facing portion would likely be available this Spring so we’ll be sure to keep you updated when we hear more on when this information is available to you.