One of my favorite things to do is riff on Bay Area real estate and tech — of all kinds, residential, commercial, retail … and Justin Bedecarre has been working with San Francisco founders for almost a decade in the commercial real estate market. He’s now a founder of HelloOffice, a technology-powered commercial real estate brokerage. We talk about what 2017 holds for the office market.

Q: Tell me what you do.

Our whole goal is to make looking for office space smarter and faster. We’ve replaced all the PDFs, spreadsheets and paperwork. We have a platform to collaborate with our clients and manage the entire deal from start to signing. We also come from the world of startups and real estate brokerage. We have both pedigrees. We’ve walked in our clients’ shoes. The storylines we’ve experienced personally are really relevant.

Q: What’s an example?

Let’s say you’re a company that’s just raised a $20 million Series B and you need 20,000 square feet and you’re moving up from 5,000 square feet. You need space that can house 200 people that you’re either going to outgrow or never fill and sublease in the next 18 to 24 months.

In this market, you’re looking at five-year leasing deals that probably cost $1.5 million a year. If you are not profitable and need to raise another round to fulfill the entire lease, you may spend up to $1 million just in security deposit.

You’ve just committed to spending $10 million. You’ve just wiped out half your round on a lease!

Q: That’s crazy.

So if you can figure out ways that companies won’t need to do that — and that’s what we’re able to do through looking for two-year subleases, plug-and-play and fully furnished spaces — the cost savings are crazy.

Q: Why does the market still do five-year deals even those are obviously a poor fit for the life-cycle of tech companies?

The chips are stacked against startups. Most startups don’t want to do these deals. At this stage, it doesn’t make sense unless there is a really unique opportunity. But the industry is built around longer-term deals.

For the landlords, turnover costs money and downtime, especially if they have to invest money in building out the space. Construction costs have skyrocketed since Title 24 went into effect, which can add an extra $25 per square foot to a build out.

For brokers, we are incentivized to do longer-term deals. Like I said, the chips are stacked up against startups when it comes to leasing office space, not to mention that rents are really high right now, and so landlords want to lock in those rents. The whole industry is based on longer-term leases. Five years, by the way, is not that long. New York leases are often 10 years. SF landlords look at seven years as a long term.

Buildings are bought and sold on expected lease terms of that size — coupled with the fact that it’s the top of the market.

Photo: Getty Images/Mitchell Funk/Photographer’s Choice

Q: How do you know we’re at the top of the market and what should founders do to plan around that?

First of all, rents have plateaued and have stayed that way for most of 2016. The high was the third quarter of 2015 and average rents are $72 per square foot across the city.

I think, however, that with all of these stats, everything deserves context. If you’re east of 4th street, you’re looking at $72 to $76 rents. If you’re west of 4th street, you’re looking at $60 to $62 rents. Then down on 9th street, you have companies like Planet Labs, Code For America and Thumbtack, which have beautiful spaces at much cheaper rates. A lot of these companies got locked into longer leases in 2015, because tenants had a lot less leverage then.

But we’re also seeing close to 3 million square feet of subleased space. Subleasing is the big story of 2016. We’re going to set a record for more subleased space than any other year in the city’s history.

Q: What does that mean?

The most important story of 2016 has been subleasing. If you look only at the number of subleases that come to market, it’s easy to use that as a negative indicator of the overall market and economy. People are thinking, “Companies are downsizing — the market must be turning!” But that is only part of the picture. You have to also look at whether those subleases get leased by other companies.

Not every company is going to work. Just like with talent, the reason the Bay Area talent pool is so strong is that there are other places to go if a company doesn’t work out. It’s the same thing for office space. The subleased space that is going on the market is getting filled, if you look at the whole picture.

So if you’re thinking about doing a Series B round, and you’re looking at a five-year lease that sends $10 million out the door, there are two ways of dealing with that.

You can warehouse space, take down 25,000 to 35,000 square feet and sublease 20,000 to grow into later. That can work, but it’s risky. Or you can plan to leave in two to three years with the mentality that this is not going to be that much money and you can find a subtenant to fill it.

Some founders are thinking that $10 million is worth a lot more to them now than it will be later, especially because many companies aren’t profitable. If you could spend $3 million on sub-leasing with a plug-and-play space, that’s an extra $7 million you’ll have to spend on talent.

I’d say with most companies we see, they need another round of financing to fulfill the lease obligation. So there’s a huge amount of pressure from everywhere as the board expands and as companies have to hire.

Q: If we’re at or near or past the top of the market, what happens when the office market weakens? Like what happened last time after the dot-com bust?

People were doing deals in the $120 to 130 a square foot range back then. Companies were doing long-term deals for spaces they never occupied with zero revenue.

We talk about this a lot. It is different this time. Something is going to happen, but it’s not going to be all of these companies failing simultaneously because they didn’t have legitimate business models.

That will be the case with some. A lot of our clients are not profitable but they have a path towards it, and a lot of the same landlords are still around and they’re not doing the deals they did in 2000. This is not that. This is not the dot-com era.

Q: But interest rates are rising and that shifts the balance of how capital is allocated between risky and less risky assets. Then there’s the new administration and whatever unpredictable effects it may have on equity markets and the IPO window. So what happened the last time around?

So if we’re at $72 today, you can look at both sides of the cycle. In 2009, people were doing deals at $19 a square foot at 410 Townsend, which is the TechCrunch building. Five years later, it was $70.

That area caught both sides of the boom. SOMA wasn’t what it is today. When you see all of these cranes in SOMA, you get this feeling that there’s a lot of space.

Q: But the new buildings being built are mostly pre-leased, right?

Not all of it. Over the next two years, 4,500,000 square feet of new buildings will come online, and less than half of that is spoken for.

Q: That is like 30,000 workers’ worth of office space. We’re only slated to bring on about 3,200 housing units next year, and then 2,500 in 2018. Proposals for even newer projects have fallen to a four-year low because real estate developers are waiting to see where the city’s new affordability requirements will fall. Voters passed an initiative over the summer to raise them so that 25 percent of every project is below-market-rate.

But a city controller study said this is too high and is financially infeasible. Landowners may not sell to developers at that level because it doesn’t buy them out of their existing cash flows of whatever businesses currently operate on their property, like gas stations, or developers may decide that they can’t spread the cost of producing affordable units — which can also cost around $700,000 to 800,000 a unit to build — across the price of the market-rate units. And if developers expect to lose money, they won’t build. So that just benefits the financial interests of the existing property and homeowners in the city, because the shortage is exacerbated.

The Board of Supervisors have put themselves in a difficult position. It will look bad politically if they lower the affordability threshold from 25 percent. However, it’s possible that with the California state density bonus law, they may come to a compromise that maintains that number but awards height bonuses to get there.

Totally. It’s just too expensive to live and work in the city. This will not just drive people to live in the surrounding cities and commute in, it will drive companies to set up offices out of state.

Q: Not every tech company needs to be in the Bay Area. There are lots of other great American cities. However, I think the idea that you can just stop building housing and that the industry will get squeezed out and move elsewhere is naive. What actually ends up happening is that companies move their middle-income jobs, like sales and account management, to lower-cost American cities like Phoenix and keep their executive and highly compensated technical jobs here in the Bay Area. It actually entrenches this overarching trend of the loss of the middle-class in the region.

That’s exactly what’s happening. Everyone’s doing it. Gusto is expanding in Denver, Thumbtack is adding in Salt Lake City and Metromile is doing it in Tempe, Arizona.

Q: Anyways, I was reading that most of the office space was pre-leased earlier when people were concerned we were running up against 1986’s Proposition M, which caps the amount of office space that can be built in SF in any single year.

The looming Prop. M cap encouraged a lot of landlords and developers to build, as you can see by all the cranes around SF, especially in SoMa and Downtown. If your building was coming online in 2015, it was pre-leased. The buildings coming online in 2017 and 2018 have had a harder time, but that’s not to say they won’t lease up.

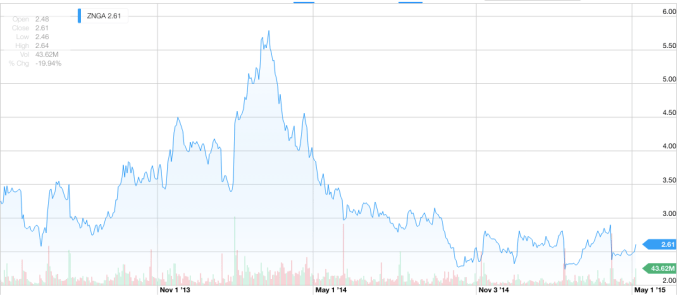

It’s just that 2015 leasing market was crazy. And then LinkedIn crashed in early February of 2016 losing half its value in one day, I think it was a Friday, and that was a turning point in the market. Perception changed from the market being unstoppable to founders and their investors having uncertainty. VCs became outspoken and startups cut costs, and things started to normalize in the real estate market, and we ended up having a very stable, healthy year in leasing.

Both 181 Fremont and Salesforce Tower are topping out soon, and have more than a million square feet available between the two of them.

Half of 350 Bush is still available. The other half of that building is Twitch. And then there are two more towers. One got approved and the other broke ground. You have the Flower Mart being developed, tower going up on Townsend and 4th right across from the Caltrain. You have the developments in Dogpatch like Pier 70, Hooper and of course the Warriors. A lot is getting done this cycle.

But there are also still challenges. We need the square footage. More companies are coming to SF and those companies are staying. It wasn’t always the case that tech companies were headquartered in SF. They would start here and then they would leave and scale in Silicon Valley. A lot of that changed with Marc Benioff committing to SF. Then after Salesforce, there was Zynga.

Q: Which owned a building that eventually became worth more than its business….

Mark Pincus has always been super savvy on real estate. After Zynga, there was Twitter, which secured a deal with employee tax incentives in mid-Market.

Q: By the way, those Mid-Market tax incentives are set to end in 2018, and perhaps sooner if the Trump administration makes good on its promise to revoke funding from “sanctuary cities.” So if that happens, San Francisco will need to make up for foregone revenue.

Oh, OK. And then Pinterest is building a campus. Stripe is building a campus. Uber has scaled tremendously. There’s also Airbnb. These companies that are paying a lot of money to scale in SF.

People want to live in SF, but it’s getting harder and harder. So it will be interesting to see what happens in the next cycle when the talent can’t afford to live here. If you’re based in SF, you can pull from East Bay talent, Silicon Valley talent, SF and then the North Bay. That’s why it’s so important. It’s the hub.

Q: Isn’t it because the large companies like Google, Facebook and Apple have basically exhausted a lot of the space in the peninsula too? Like certain spaces in Palo Alto are north of $100 per square foot, which is way higher than what you see in SF.

Two of the three most expensive streets in America for commercial real estate are in the Bay Area. One is Sand Hill Road in Menlo Park and the other is Hamilton Avenue in Palo Alto. Facebook and Palantir became the anchors throughout this cycle and were the only new companies that were able to scale to any large level. There are also smaller companies like SurveyMonkey and a handful of others in Palo Alto.

But there’s still a lot of space in the rest of Silicon Valley. I don’t think it’s a supply issue. I think that fewer people want to go to Silicon Valley to work. But all of these companies are scaling past — way, way past — the amount of people that can live here.

Q: What do you think were the biggest office deals of the year?

- Twitch was a big one. They leased 185,000 square feet in a building that isn’t even built yet. It’s been amazing to see them grow from their roots as Justin.tv from the first Y Combinator class.

- Then when Twitter put their space out on the subleasing market, it was taken up by NerdWallet and Thumbtack. So that’s a really good example of what a healthy market looks like. These companies took advantage of plug-and-play, fully furnished space.

- Then there was Charles Schwab — staying, rather than leaving. That was a big deal. They took 400,000 square feet at 211 Main after concerns they were going to move to a cheaper market and leave their hometown.

- For the East Bay — and I’m not an expert there — there was the Uber deal.

Q: It’s interesting that a lot of people aren’t really paying attention to what happened after the Uber deal. So Lane Partners, the developer that bought the Sears building at 19th Street BART for $25 million in 2014, put $40 million of renovation work, then sold it to Uber for $123.5 million the following year, they just proposed another huge deal at the end of November. They pitched a 1.3 million square foot deal, which is more than three times the size of the Uber building, one block away.

Oakland’s vacancy is 5 percent. It’s really, really tight. It’s totally about supply.

Q: But Oakland has historically had many entitled office projects. But few projects are actually being built.

That’s because it’s just as expensive to build there as in SF, but you get much less in rent.

There’s so many macro-level issues. Will SF still be as appealing when the talent can’t afford to be here? Transportation is a major factor around where buildings are being built. It has to be unprecedented with how many more people are coming downtown and we basically have the same transportation system from 50 years ago, and similar levels of parking.

I’m really interested in seeing how the transportation changes over the next cycle.

Q: I’d bet on autonomy before the infrastructure improves. We passed a $3.5 billion BART bond in the last election, and it includes some funding to study a second transbay tube, but that will take a few decades to complete if we’re successful.

Wow.

One other issue we’re seeing is that the city has started to crack down on zoning. They set up a zoning task force.

Q: This is between office and industrial or PDR (production-distribution-repair) space, right?

Yeah.

Q: The reason they created that category about a decade ago is because they wanted a mix of uses. In the last cycle, office was cannibalizing all these old industrial spaces, which was undercutting more of this middle-income job base that sits in between white-collar office work and service labor, which is extremely low-wage. While the city has leaned very heavily into tech, you don’t want to be all tech. A city needs to have a diversified basket of industries and jobs, just like you’d have in a financial portfolio. Protecting certain kinds of space ensures that. Otherwise, literally everything becomes condos and office because that’s the highest-value use of the underlying land.

On the one hand, I get it. But it creates other problems. Industries mature and change and then you have these dying industries and you can’t adjust because the laws are in place to where tenants can’t lease a building.

Q: On the other hand, the PDR category inadvertently created space for hardware startups that trades at something like 30 percent discount per square foot compared to pure software startups.

Yeah, that’s great. But it’s the way that this is enforced and has become politicized. For many years, this wasn’t an issue. Then all of a sudden it was and many companies got hurt. They were in spaces that they didn’t know they weren’t zoned for, then they got a call and were kicked out.

Then the other problem is figuring out space for non-profits. ECS (Episcopal Community Services) is one of our clients. [Editor’s note: ECS is a nonprofit that, among many other things, runs a program training people experiencing homelessness to become restaurant chefs.]

ECS was scouring the market for a space that they could afford, and the only ones that qualified were skirting the lines of what was legal. They decided not to go down that path but it was hard.

Q: What is the nonprofit market like?

It’s hard. A lot of nonprofits are paying in the teens and twenties and have leases expiring soon. We’re working on some initiatives to leverage our platform to get the large tech companies to offer and match excess space to nonprofits that need it.

Q: What should you do about office space if you’re a founder and you’re planning to expand?

When I think about companies that need to expand, I think about a hermit crab. The shell you’re in now is not going to be the shell that you’re in two years from now. Optimize around shorter-term plug-and-play space. You can still make it your own, and you preserve capital to invest in talent, which is incredibly important.

Q: What if you’re downsizing?

When you think about companies that are downsizing, you need to make your space as plug-and-play as possible. Never over-optimize around making yourself whole again. Cut the damage, cut your losses, and move onto the next thing. It’s still a good time to sublease. There’s plenty of demand out there as long as you position it correctly

Q: What’s the advice you keep having to repeat over to founders looking for space?

- Give yourself enough time to search. We’re often having that conversation with founders way too late. If you’re looking for anything around 2,500 square feet and above 5,000 square feet, give yourself at least three months. When you really boil it down, it only takes a few weeks to see spaces. But what if those spaces don’t work out, then you have to wait for another fresh supply of space. If you find a space in two weeks, it takes another two weeks to negotiate back and forth and then you have to set up Internet and furniture.

- You should account for $15 per square foot on the low-end and $25 per square foot on the high-end for furniture. If the space isn’t wired, then I’d say account for $30 per square foot in set-up costs.

- The most important thing when approaching a search is understanding what your headcount is going to be in 18 to 24 months. For startups, that’s as far out as they can predict. I’d apply 100 square feet-an-employee to the top end of that.

Q: Not 150?

- No. You can definitely get space to fit that, but you don’t want to be swimming in it when you’re smaller. 150-square-feet-per-person is a good benchmark for where you want to be at a steady rate, but startups are not steady.

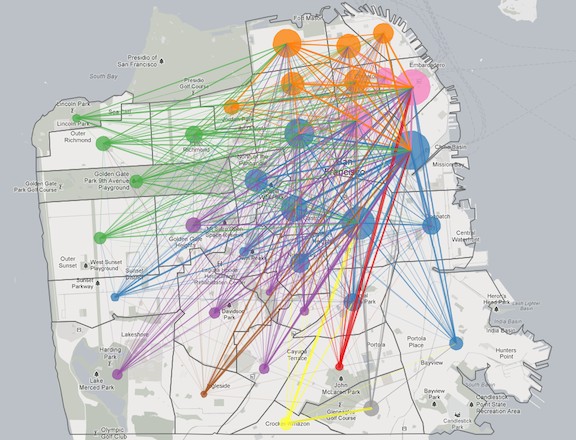

- Understand where your employees are coming from, or where you want to recruit from. Understand whether you need to be around Caltrain or BART, for example. If you’re coming from the South Bay, you’re probably not going to join a company in Jackson Square.

Q: What about the impact of space on your company culture?

We talk a lot about what the dynamic of your team is from engineering to sales to operations. Some engineers like to be isolated. Some like to be more collaborative.

You should understand the dynamic of how you want people to interact and how you want people to meet and run into each other. That will dictate what kind of space and vibe you’ll have and what the ideal layout is.

It’s definitely a balance. The two things that employees complain about are not having enough bathrooms and not having enough meeting space. You’ll need to have a balance of phone booths, small meeting rooms and a limited number of larger meeting rooms. You need space that allows people to escape into different environments. If a big part of your culture is having meals with the team, then you have to build around that.

Q: What about open office plans?

I think there’s no perfect answer to that.

Q: What about having a really polished office space that makes you feel like you’ve arrived maybe when you haven’t yet?

The vibe and message that you want to send with the office is a trailing indicator. The office doesn’t define the company culture. The culture defines the office.

A lot of our clients have the mindset that they don’t want people to feel like they’ve made it. They want to feel scrappy. But you have to make sure there’s a balance between having a warehouse feel and have it feel productive.

Q: Do you have any predictions for 2017?

I don’t know if this is a cop-out, but I think it’s going to be a steady year. Things will calm down in terms of the perception of construction when 181 Fremont and Salesforce are finished.

Q: Tall towers tend to be lagging indicators. The last tallest tower we had in this city was the Transamerica Pyramid, which was 1972, the year before the Oil Crisis. Then if you look at New York, the Chrysler and Empire State Buildings were finished or nearing completion around the 1929 crash.

That’s because it takes so damn long to build. Developers aren’t investing in this cycle. They’re investing in the next one.

This year though, it’s hard to say. Venture is not shutting off this year. These funds are way too big. So something that we don’t know about has to happen.

We’re a good distance away from when LinkedIn crashed, and everyone tightened up, cut costs and started focusing on getting to profitability. The biggest companies in the market are ones like Slack, that aren’t proven and aren’t sure things. But they are making a lot of money and have a lot of investment behind them.

Then you’ve got Uber, which is a major, major tenant and will be a driver of jobs in Silicon Valley, the East Bay and San Francisco going forward at a much larger scale. They increased their local headcount by more than 80 percent in 2016.

And you have Salesforce, the largest tenant in the city, with more than 6,000 employees. When they combine into that single tower, they’ll leave several hundred thousand square feet of office space in the surrounding area.