If you wanted to see in the dark, you could do worse than follow the example of moths, which have of course made something of a specialty of it. That, at least, is what NASA researchers did when designing a powerful new camera that will capture the faintest features in the galaxy.

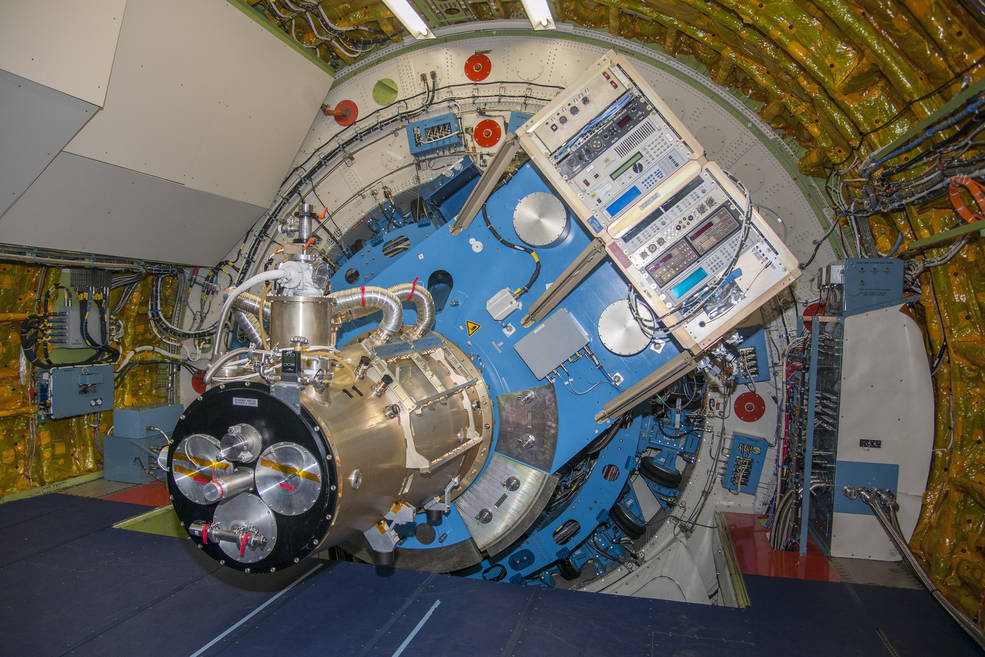

This biomimetic “bolometer detector array,” as the instrument is called, is part of the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy, or SOFIA. This ongoing mission uses a custom 747 to fly at high altitudes, where observations can be made of infrared radiation that would otherwise be blocked by the water in our atmosphere.

But even the infrared that does make it here is pretty faint, so you want to capture every photon you can get. The team, led by Christine Jhabvala and Ed Wollack at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, originally looked into carbon nanotubes, which have many desirable properties. But they didn’t quite fit the bill.

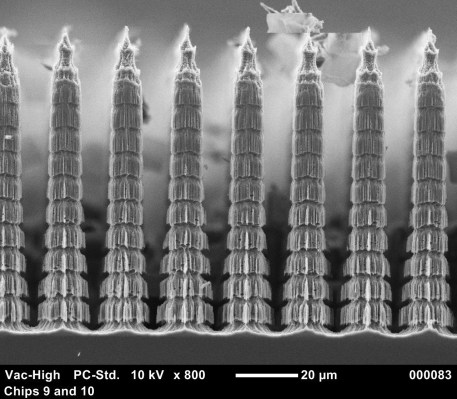

The eye of the common moth, however — or at least, a design inspired by it — did what the latest nanomaterial didn’t. Insects’ eyes are of course very different from our own, essentially composed of hundreds or thousands of tiny lenses that refract an image onto their own dedicated photosensitive surface at the base of a column or ommatidia. In moths, this surface is also covered in microscopic, tapered columns or spikes. These have the effect of preventing light from bouncing back out, ensuring a greater proportion of it is detected.

The team replicated this design in silicon, and you can see the result at top. Each spike is carefully engineered to reflect light downwards and retain it, making the High-Resolution Airborne Wideband Camera-plus, or HAWC+, one of the most sensitive instruments out there. Funnily enough, the sensor they modified was originally called the backshort under-grid sensor — BUGS.

HAWC+ not only pulls in light from the far end of the infrared spectrum, but measures its polarity. This means the slightest changes in the light’s nature or origin will be detected. Dim features and events like early star formation and the black hole at the center of the galaxy can be observed more closely than ever before.

HAWC+ not only pulls in light from the far end of the infrared spectrum, but measures its polarity. This means the slightest changes in the light’s nature or origin will be detected. Dim features and events like early star formation and the black hole at the center of the galaxy can be observed more closely than ever before.

“You can be inspired by something in nature, but you need to use the tools at hand to create it. It really was the coming together of people, machines, and materials. Now we have a new capability that we didn’t have before,” said Wollack in a NASA news release. “This is what innovation is all about.”

SOFIA is underway, but the new sensor was just commissioned, so it’ll be a while before it can be built to spec and integrated with the rest of the platform. You can keep up with it and the rest of the observatory’s science on the mission webpage.