Users of WeChat, China’s most popular messaging app, have stopped being informed when their messages are being censored in a move that further erodes user privacy, according to a new report from Citizen Lab.

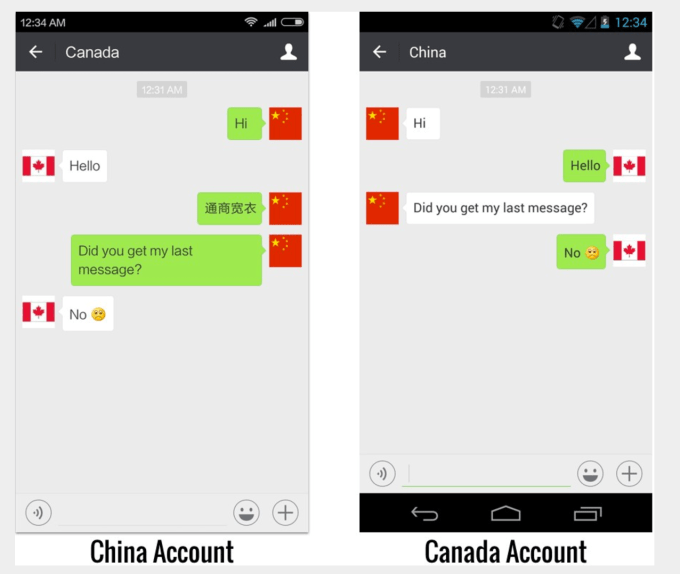

Tencent, the $232 billion dollar giant that operates WeChat, has always practiced forms of censorship on its users — that’s an inevitable part of running a popular online service in China — but at some point in recent years it ceased informing users when their messages were blocked. In the past, the app would notify users when a message they intended to send wasn’t delivered because it was controversial, such as references to free speech groups or the Tiananmen Square massacre. Now, however, censored messages are simply not delivered with no notification for either sender or recipient.

“By removing notice of censorship, WeChat sinks deeper into a dark hole of unaccountability to its users,” wrote Ron Deibert, who is director of Citizen Lab, a research unit within the Munk School of Global Affairs at the University of Toronto, Canada.

The development is troubling, but even more so when you consider the scale of WeChat, which has over 840 million active users each month and has become an essential platform that includes payments, taxi-hailing, news services and food delivery.

That notification change is one of a number of alarming findings from the report, which Deibert believes is “essential because it helps pull back the curtain of obscurity that, unfortunately, pervades so much of our digital experiences.”

Citizen Lab tested censorship using a range of WeChat accounts created in China, the U.S. and Canada

As you’d expect, WeChat’s censorship apparatus is strongest in China. (Although we’ve known for some time that there is censorship of international users, too.) The report showed it tracks more keywords for China-based users and China speakers. It also blocks more URLs from loading within the in-app browser, the default when opening a link from inside the app, for Chinese users than it does for those overseas.

Yet, one of the most interesting takeaways is that WeChat’s censorship system — which is triggered by an ever-evolving set of keywords that is stored server-side — follows users with links to China across the globe. That’s to say that if an account is paired to a Chinese telephone number, then it will continue to be subject to China-based censorship even if it is used on networks outside of China or if it becomes attached to an overseas mobile number.

So, in essence, the ‘WeChat China user’ label is one that sticks for life. That means that traveling academics, students who go overseas to study and basically anyone who leaves China physically will remain within the boundaries of the country’s internet censorship system.

Tencent doesn’t provide guidance as to how many overseas users WeChat has, but the bulk of them are likely to be located in China, where WeChat is estimated to account for one-third of consumers’ time spent online. In light of that, Citizen Lab found that its censorship efforts are sharpest in China and, in particular, group messages which have become increasing popular social tools.

WeChat allows up to 500 participants in a group, and they have replaced social networks in many ways by providing a space for families, colleagues, industry-peers and others across the board to communicate. Citizen Lab found that keyword censorship was more active in groups, presumably to play down the higher potential to spread information across large numbers of users.

Tencent didn’t respond directly to specific findings of the report in a statement provided to TechCrunch:

Tencent respects and complies to local laws and regulations in countries we operate in to provide a safe and reliable communications ecosystem for our users. WeChat has and will always adhere to Tencent’s core mission to create value for our users by providing high-quality, secure user experiences.

The discussion around censorship in China has heated up recently after the New York Times reported that Facebook had developed a system that could be deployed in China to censor content. The U.S. social network has never shied away from its interest in China but, as I wrote last week, the popularity of established services like WeChat mean that simply being relevant in the country would be a huge challenge for Facebook, assuming that it could find an agreement to enter that suited the Chinese government.

The full Citizen Lab report can be read online here.