The European Space Agency is doubling down on Mars, dedicating nearly half a billion dollars to its follow-up mission to the planet’s surface — even though the first one quite literally cratered. But an ambitious joint plan to redirect an asteroid’s moon has been scuttled in order to find the funds.

In October, the ESA hoped to join NASA on the surface of Mars with its Schiaparelli robotic lander. But the craft failed to descend properly and plummeted more than two miles to the ground, ending up as little more than a scorch mark. The orbiter that delivered Schiaparelli to the planet, fortunately, is operational and performing admirably.

A similar fate befell Beagle 2, another ESA lander, in 2003. So it would be understandable if they decided to at least temporarily abandon an enterprise that appears for them to carry a curse.

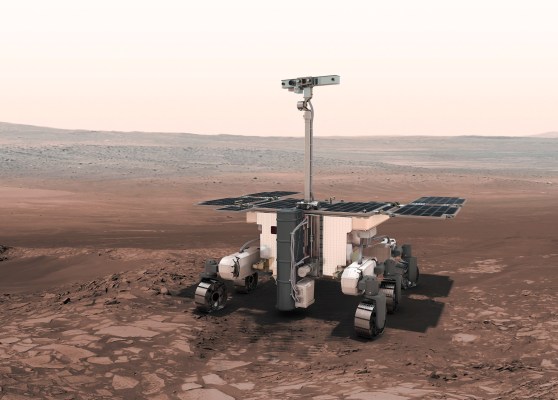

But at a major meeting in Switzerland, the ESA member states maintained a stiff upper lip and committed €436 million (about $464 million) to the ExoMars 2020 project — a relatively small part of the more than €10 billion it negotiated to fund the rest of its missions.

Like the first ExoMars, this one is a collaboration with Russia’s Roscosmos; €339 million of the remaining costs (it’s been underway for a while) will be provided collectively, but €97 million had to come from within the organization — meaning other projects would be the casualties of Europe’s Martian ambitions.

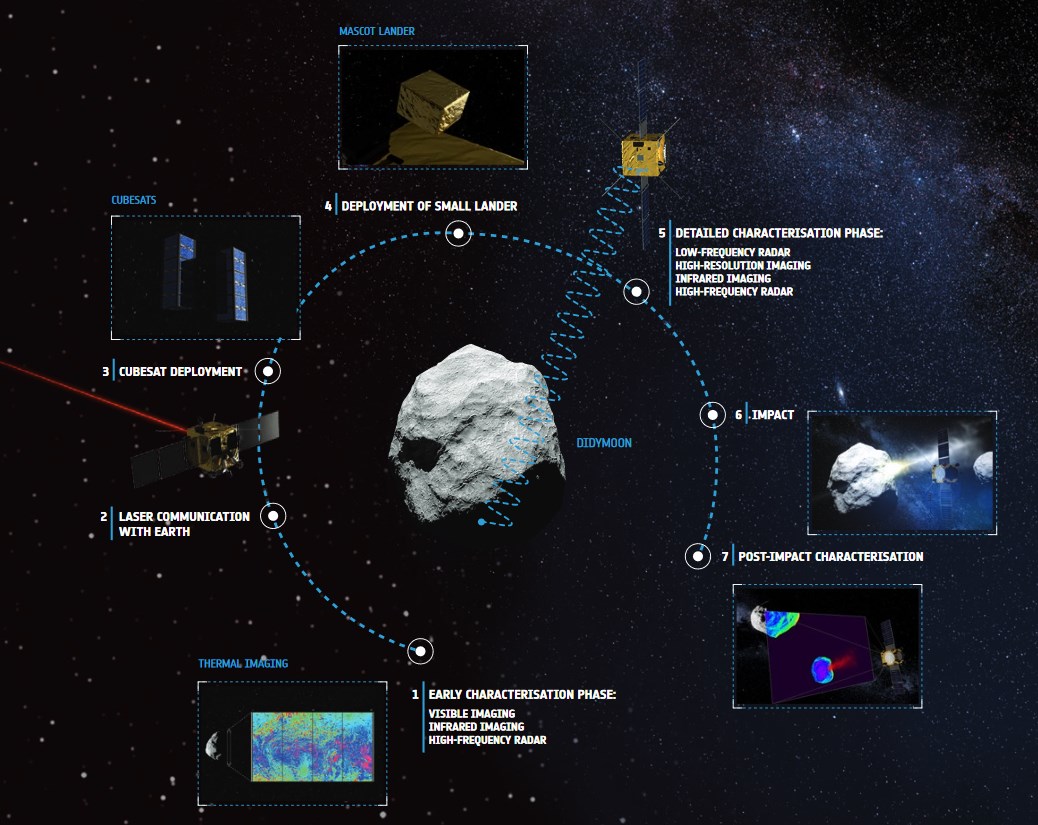

Scrimping and saving here and there may have turned up a few millions, but in the end, the choice was made to cancel the agency’s Asteroid Impact Mission. This was a pair of probes and a lander that were to be sent to the asteroid Didymos, where they would closely observe the results of a second mission, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test, which, as you might guess, involved hitting a space rock really hard and seeing what happens.

DART, actually a NASA mission, will continue, but AIM will no longer be accompanying it. It’s a major loss, because now the impact will have to be monitored from the ground, yielding only a fraction of the data AIM would have gotten, and at a fraction of the precision.

Patrick Michel, the French planetary scientist who led the AIM project, told Nature: “A cool project has been killed because of a lack of vision, even short term, and courage, and this is really sad.”