We’ve got machine learning systems captioning images, synthesizing speech and translating between languages, but it seems we’ve been neglecting their cultural development. Would you believe the future rulers of this planet are largely ignorant of classical music altogether? It’s bad enough humanity will be enslaved — but by an entity so vulgar? A new project looks to change that with a data set of pieces from great composers, annotated so the computers can follow along.

MusicNet, conceived and compiled by University of Washington researchers, is an attempt to create a data set that is to analyzing classical music what the widely used ImageNet is for computer vision.

It isn’t the first time machine learning has encountered music, by a long shot, but MusicNet is more about establishing a standard set of data to learn from and score by. ImageNet, for instance, is used by researchers and students both to train and evaluate computer vision systems, and other data sets can be used for translations, faces and so on.

To start with, MusicNet comprises 330 classical music recordings available for free online from a number of sources; it’s heavily weighted toward Beethoven and solo piano because, well, Beethoven’s piano work is pretty popular. But there are also dozens of works by Schubert, Brahms, Mozart, Bach and so on — though, disappointingly, no Chopin.

Each live recording is annotated by matching it to a score, with each note indicated down to the millisecond. That would normally be an extremely labor-intensive process, but the team used a technique called dynamic time warping to map the ideal written score to each performance, in which creative liberties and the innate variability of human execution cause digressions from the original. The automated approach (still manually checked by human musicians) both improves precision and makes processing music far less laborious.

“Features are traditionally hand-crafted in the the music community,” wrote John Thickstun, lead author of the paper describing MusicNet, in an email to TechCrunch. “This is analogous to that state of affairs in the vision community a decade ago, before deep models trained on datasets like ImageNet replaced visual hand-crafted features with learned ones.”

The team set a few machine learning systems to the task as a test run: the models were trained up on the MusicNet data, which would presumably allow them to associate notes with aspects of the recording associated with them.

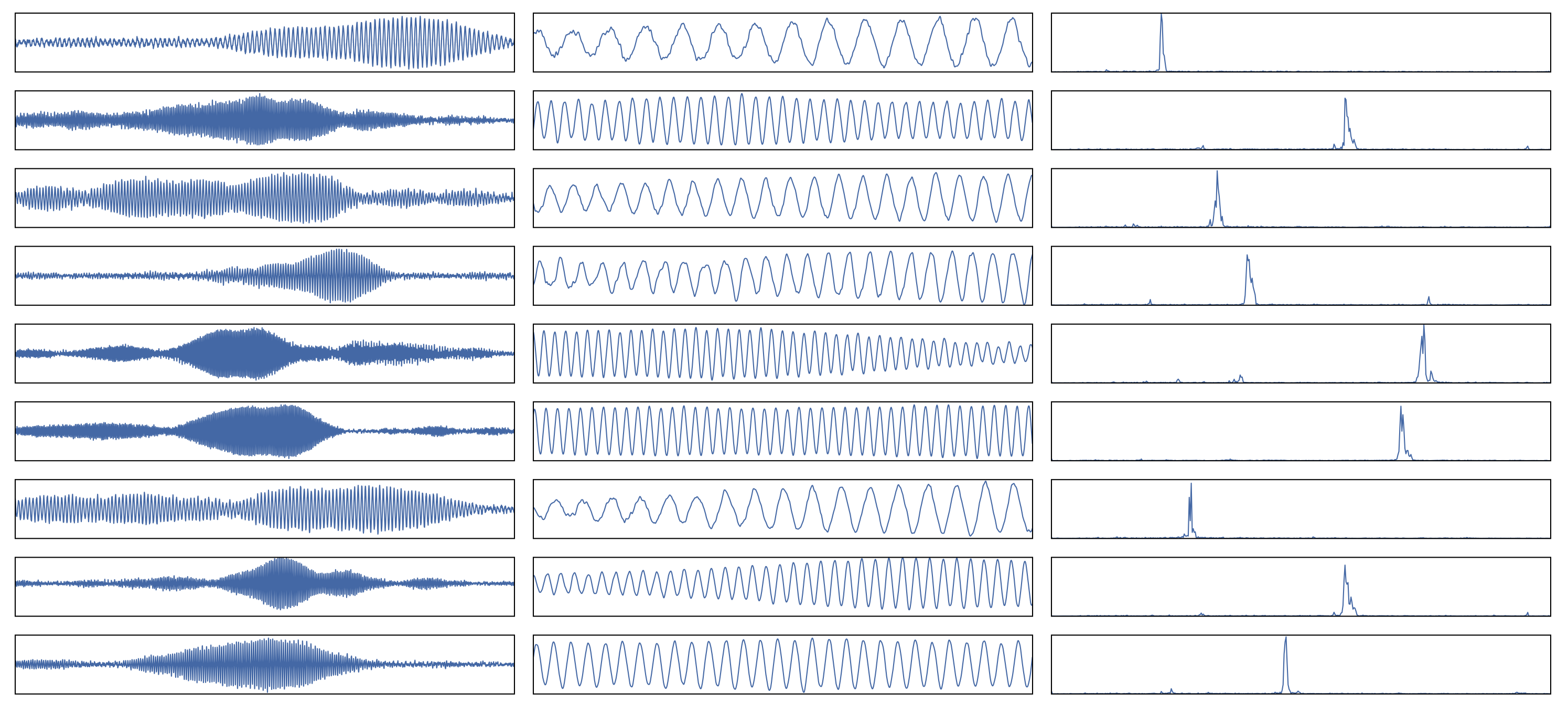

Visual representation of how the model extracts basic note data from raw audio (whole note on left, weighted center in the middle, analysis of that weighted area on the right).

“We asked our networks to guess which notes are played in segments of recordings, and the networks discovered features they find useful for this task,” explained Thickstun.

Early results are heartening: Models performed better when trained on MusicNet than on traditionally annotated pieces, producing more accurate note maps when presented with novel recordings.

Just as computer vision systems began only being able to say whether two images were the same or different, or whether an object was square or not, the nascent music analysis models are in their infancy. Basic tonal differentiation is a start, but of course there’s much more to a piece of music than “B for 150 milliseconds, C+E for 300 milliseconds,” etc.

“In future work, we plan to build deeper networks that learn more complex features,” said Thickstun. “We hope these networks will be able to learn higher-level musical concepts like melody, harmony, and rhythm.”

Adding more music to the data set, which the creators urge other researchers to do, will help broaden and deepen the understanding of any model trained on it. Eventually, as other neural networks and deep learning systems have demonstrated, they may one day create their own works.

You can read more about the methods and models behind MusicNet in the team’s paper at Arxiv, or at the project’s webpage.