There’s a general malaise growing around IoT. After years of hype, more hype and even more hype, people are now starting to wonder: Where is this shiny, artificially intelligent, fully connected future of things we were promised?

Certainly a botnet of hacked IoT devices launching one of the largest DDoS attacks ever seen has not helped.

Part of the problem, like with any massive transformation, is because of the nature of exponential growth curves: Change takes time, and will come more slowly at first.

But the other problem is us: Our stubborn attachment to a label that, for example, places wind turbine vibration sensors in the same jargon-bucket as a voice-activated home speaker that can control our lights.

This giant market we call the “Internet of Things,” encompassing everything from wearables to autonomous vehicles to smart homes/factories/cities, simply does not exist.

Yes, there is change afoot, transforming our industries, lives and world. Change driven by fundamental technological shifts: cheaper, more powerful hardware; nearly ubiquitous connectivity; cloud computing.

But there is no broad, homogeneous set of applications that we can call IoT. Instead, there are many, varied sets of applications, each enabled by the same tech trends, but manifesting themselves in different ways.

In order for us to ensure that we develop a world where the benefits of connected devices outweigh their risks, we need to start looking more closely at what is going on.

Many IoTs

We are witnessing an evolution of computing, as it expands from mainframes (one computer for many people) to desktops (one computer per person) to mobile (multiple computers per person) to the phenomenon we see today (one-to-many computers per “thing”).

We are entering a new wave of computing … one driven by a world of connected devices.

But the devices in this latest computing wave are different in an important way from the ones before it: They’re incredibly diverse.

PCs were nearly identical, almost all running the same OS (if you remember, we even called them “clones”). Mobile-phone hardware is somewhat more varied, but we’re down to two operating systems (and the need for app developers to have a consistent set of APIs has reduced hardware variability even more).

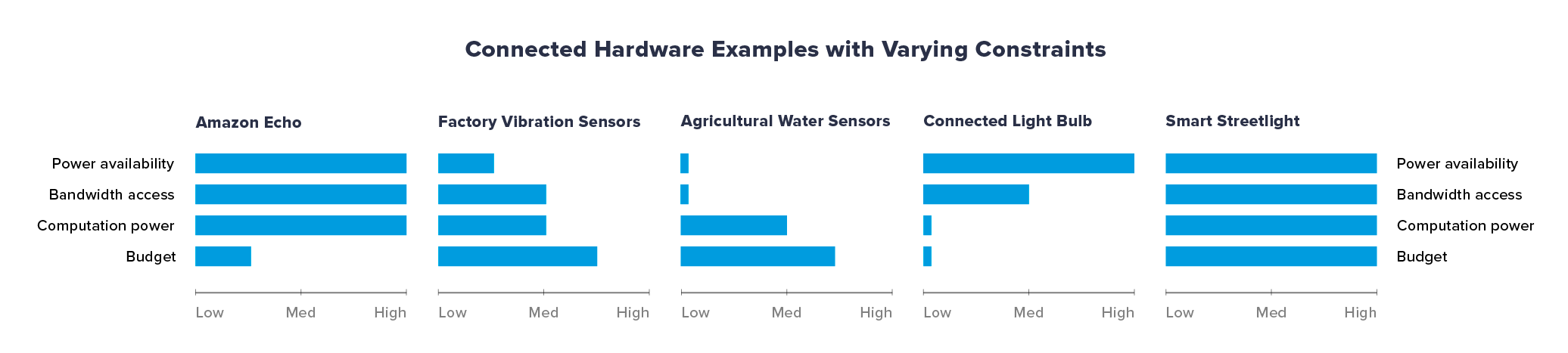

“IoT” devices, however, are defined by a variety of constraints: available power, connectivity/bandwidth, computation, cost. Often these constraints are entwined: less available power → lower power data transmission (or longer duty cycles between engaging the radio) → low available bandwidth.

These constraints are set by the environment within which these devices are serving. For example, connected home products are often not energy limited (powered via electrical outlet) and enjoy high bandwidth (via Wi-Fi/Ethernet), but may be cost-constrained by consumer budgets. On the other hand, sensors used in oil and gas may have a larger budget, but with limited power and network access because of the remote nature of the work.

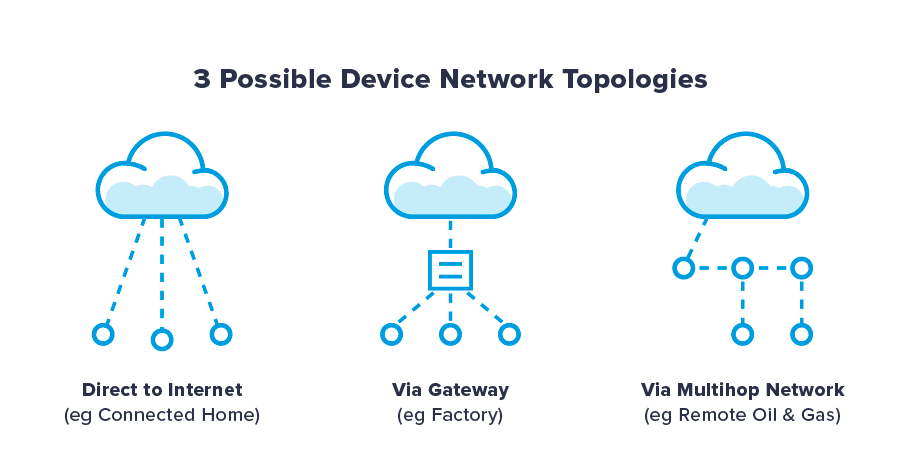

These constraints can also translate into entirely different network topologies. For example, your Amazon Echo talks directly to the internet via Wi-Fi. But in a factory, low-powered sensors can communicate via a low-power protocol (e.g. Zigbee) to a local gateway, which then could use Wi-Fi/Ethernet to communicate upstream. And in a remote mine, sensors may communicate via multi-hop mesh back to a gateway, which may then use a cellular network to transmit upstream.

And of course, these environments can also lead to entirely different businesses: e.g. a direct-to-consumer or retail model for consumer products, an enterprise sales model for industrial sensors or an RFP-driven process for smart-city devices.

And of course, these environments can also lead to entirely different businesses: e.g. a direct-to-consumer or retail model for consumer products, an enterprise sales model for industrial sensors or an RFP-driven process for smart-city devices.

There is a rich diversity at work here, far greater than what we have seen before in PCs or mobile phones. These “Internet of Things” devices represent a broad spectrum of reds, greens, blues, violets; yet we continue to lump them all under a bland white umbrella, losing what makes each color so unique. And this hampers our ability to understand and serve these markets.

Expanding our world

Let’s be clear: We are entering a new wave of computing, one that will engender even more change than the ones before, one driven by a world of connected devices.

But let’s also recognize that this phenomenon is enabling change in many different ways, each of which is its own precious little snowflake: smart home, connected vehicles, preventive maintenance, precision agriculture, asset tracking, fleet management and so on.

I have no crystal ball: I don’t know how long it will take for this phenomenon to gestate across these various applications, nor which of these trees will bear fruit sooner rather than later.

But I do know that more descriptive labels will only broaden our understanding: Just look to the Eskimos, who have 50 words for “snow.” Or, as the philosopher Wittgenstein wrote, “the limits of my language means the limits of my world.”

The sooner we expand our language, the sooner we expand our world.

Thanks to Mike Freedman and Andrew Staller for reading drafts of this article.