During my Ph.D. studies, I developed a voice-activated human-robot interface for a surgical robotic system using Microsoft’s speech recognition API. But, because the API had been built mainly by 20-30-year-old men, it did not recognize my voice.

I had to lower my pitch in order for it to work. As a result, I was not able to present my own work.

Although I had built the interface, a male graduate always had to lead the demonstration when we showed the system to distinguished visitors at the university, because the speech system recognized their voice but not mine.

AI speech recognition systems have improved dramatically since the early 2000s, but there are still many AI products that have these design flaws.

It’s something that becomes problematic when it affects your target customers — like when Hello Barbie, Mattel’s artificially intelligent Barbie, struggled to recognize the voices of the very children intended to play with it (this on top of the highly controversial and even sexist content programmed into the doll).

While Hello Barbie and my own AI experience were both disappointing, they point to more profound issues in the larger picture. The lack of diversity and inclusion in AI, and in overall product development, is not merely a social or cultural concern.

There is a blind spot in the development process that affects the general public. When applied to products where safety is a factor, it becomes a question of life and death.

This is more than a complaint about the lack of diversity in engineering. Because of the dire consequences, the industry must change, especially as AI becomes an increasingly large part of our lives.

Bias in automotive design and safety

Every time you step into a vehicle, you’re putting your life into the hands of the people who made the design and engineering decisions behind every feature. When the people making those decisions don’t understand or account for your needs, your life is at risk.

Historically, automotive product design and development was largely defined by men. In the 1960s, the vehicular test crash protocol called for testing with dummies modeled after the average male with its height, weight and stature falling in the 50th percentile. This meant seatbelts were designed to be safe for men and, for years, we sold cars that were largely unsafe for women, especially pregnant women.

Consequently, female drivers are 47 percent more likely to be seriously injured in a car crash. Thankfully, this is starting to shift — in 2011, the first female crash test dummies were required in safety testing — but we are still building on 50+ years of dangerous design practices for automobiles.

Gender is only one area where there is a serious lack of diversity in design and engineering. Design bias is equally problematic when it comes to race, ethnicity, socioeconomic class, sexual orientation and more. For example, Google’s computer vision system labeled African-Americans as gorillas, while Microsoft’s vision system was reported to fail to recognize darker-skinned people.

Today, one of the most prominent applications of computer vision is self-driving cars, which rely on these systems to recognize and make sense of the world around them. If these systems don’t recognize people of every race as human, there will be serious safety implications.

I hope we never live in a future where self-driving cars are more likely to hit one racial group or prioritize the life of some races over others. Unfortunately, when a single homogeneous group is designing and engineering the vast majority of technology, they will consciously and unconsciously pass on their own biases.

A wider inclusion problem

Beyond transportation, we are relying on technology for basic needs like food, communication, education and much more. For us to live in an equal society, our technology must serve and treat all segments equally.

Let’s acknowledge that there are widespread diversity and inclusion problems with AI today. It doesn’t take more than a quick Google search to uncover a handful of disappointing occasions where we’ve seen AI blatantly discriminate against one group, including:

-

Microsoft’s Tay, an AI “teenage” chatbot that learned from interactions. Within 24 hours of being exposed to the public, Tay took on a racist, sexist, homophobic personality and had to be taken for an indefinite time-out.

-

Apple HealthKit, which enabled specialized tracking, such as selenium and copper intake, but neglected to include a women’s period tracker until iOS 9.

-

A study conducted by Lancaster University that concluded that Google’s search engine creates an echo chamber for negative stereotypes regarding race, ethnicity and gender. When you type in the words, “Are women…” into Google, its autocomplete choices are “…a minority,” “…evil,” “…allowed in combat” or, last but not least, “…attracted to money.”

Despite these recent blunders, Silicon Valley has simply moved past denial to acceptance. That’s not good enough. We need to take direct and actionable steps toward changing AI culture and creating products that are safe for all segments of society. So how do we do that?

Safer products begin with diverse teams

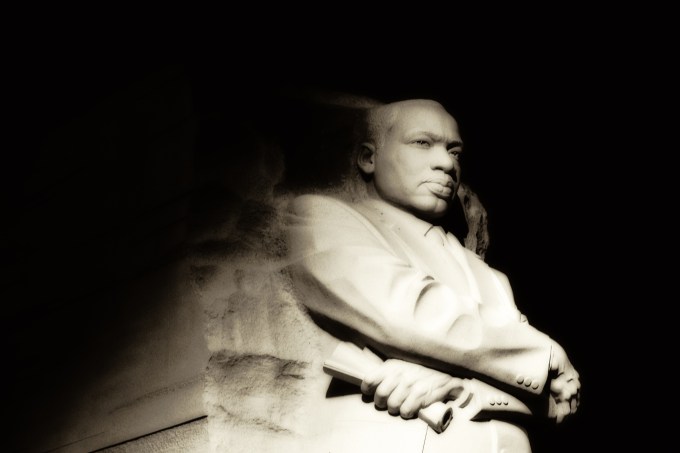

Photo courtesy of Flickr/Johnny Silvercloud

A recent study by Paysa found that 68.4 percent of those who took jobs in the self-driving car space within the last six months were men, and only 5.4 percent were women (26.2 percent are unaccounted for). Of that same group, 42.1 percent were white, 36.2 percent Asian and 21.6 percent undisclosed. Even with missing data, these numbers paint a picture of the severe lack of diversity in a space that will impact the safety of millions.

While one segment can have a certain level of empathy when developing products for others, we have seen time and again how having a homogeneous team can result in designs biased toward that particular group.

It’s tempting to think that the sheer size of data available can get around the issue. Unfortunately, that’s not the case. These algorithms work by comparing one data model to similar ones from the past — and it takes a healthy dose of human judgment to figure out the right context for a particular data model. Engineering teams have a significant hand in defining these models and, thereby, the resulting technology.

The lack of diversity in AI is not merely a social or cultural concern. It’s really a life or death safety issue.

Even the most well-intentioned developers can be simply unaware of their own narrow perspective and how that may unconsciously affect the products they create. For example, white men often overestimate the presence and impact of minorities.

The Geena Davis Institute for Gender in Media found that white men viewing a crowd with 17 percent women perceived it to be 50-50, and when it was 33 percent women, they perceived it to be majority women. A simple overestimation like this illustrates how difficult it can be to see the world from another’s perspective.

Software engineering, especially in the nascent self-driving car space, is a high-paying career path, so many are advocating that more minority groups should have these opportunities. However, there’s an even more important reason for minority groups to work in the autonomous driving field — the opportunity to design products that will impact and improve millions of diverse lives equally.

I encourage all tech companies to first be aware and honest about the current state of diversity in their engineering, product and leadership teams. Then, set trackable metrics and goals quarter by quarter. It’s important to bake-in inclusion requirements from day one and for it to be a key consideration, if not a priority, as the company and product develop.

The lack of diversity in AI is not merely a social or cultural concern. It’s really a life or death safety issue. To build safer products that recognize the equal value and humanity of all people, we must first have diverse perspectives and voices from a diverse team. I refuse to believe that it’s harder to hire minority candidates than it is to build self-driving cars.