L

ast September, in the depths of high summer, my wife and I wanted to see the Midwest again. It’s not a very common desire, this one, to drive hours between small Midwestern cities with nothing but cornfields and rest stops in between. But it was a good trip.

We began in Brooklyn and drove across the Verrazano, a bridge so long and well-engineered that its makers took into consideration the curvature of the Earth when they designed it. This spit us out out onto Staten Island, once New York’s ash heap and now a bustling bedroom community surrounded on all sides by water.

It’s the Midwest in miniature, with more hills, and it’s the place to go if you don’t want to be crowded and want a little bit of a yard. From there we plowed into New Jersey, the smoky fog giving away as we rode onto the mainland. It isn’t until the further edge of New Jersey, however, that you feel you’re leaving the city and entering the country, when the trees and towns give way to fields and the worn teeth of the Alleghenies fall away on the thin strip of West Virginia that pokes up like a cast-iron griddle handle.

America sinks to sea level as you roll into the Ohio Valley. In Pittsburgh you meet the twin rivers, Allegheny and Monongahela, where they flow into the Ohio, down the border with West Virginia, and onto Cairo, Illinois where you can hop a freight or boat going south or west. It was on this westward flowing river that settlers first came to the mythical territories – sometimes waylaid by river pirates like Samuel Mason of Cave-In-Rock, Illinois – and set up the great trading cities. It was on this river that steel flowed from the mountains into the plains and built Chicago and all points West.

And it is this river, placid in appearance as it snakes along the southern border of Ohio, that brought immigrants like my paternal grandfather Julius Nagy nee Big nee Biggs to Martins Ferry, Ohio where he worked in the mines until he got black lung and died in California searching for a cure.

The Eastern edge of the Midwest is neither beautiful nor ugly. This border is a psychological one because, from the highway, you don’t see the built-up cities that flank the girding roadways, the hidden malls behind the trees, the small towns once brightly lit and jumping with music and people and commerce but, in the 1940s, bypassed by the interstate. Ours was a path driven by soldiers and truckers and beats and hippies and jitney drivers and families for most of the last century and now, depending on who you talk to, the drive to return to the heartland is either foolhardy or full of sense.

I’m a New Yorker now. I was from Ohio. I didn’t want to go back to stay but I wanted to bear witness, to remember where I once lived and what I once loved. It’s like visiting an old friend. Both of you are older, both of you are changed, but you still have a common language, common experience. You may feel superior in some way. Maybe they never left home, maybe they got married early and suffered for it. Maybe they never finished college. But that superiority soon washes away when the reality of your meeting sets in, the way your bones are born of the same minerals, your brains born of the same education and mindset. You are linked and superiority or inferiority is forgotten because there’s love.

The Midwest of my 1970s childhood was a country full of promise. Movies set in the Midwest showed stately mansions on the edge of Chicago, waving fields of wheat, or scrappy auto workers in Detroit. The East Coast cities were all grit and broken glass and fear while the West Coast cities were dry and alien. The Midwest had secret woods and calming gardens and homes that were safe and welcoming.

The dreamer is stirring.

The story was simple: The Midwest was our best hope. The day Detroit rumbled to life and did Henry Ford’s bidding was the day our role as kingmaker was cemented. The mercantile exchanges and markets fed the nation, cows from the Chicago stockyards and wheat from Ohio making the burgers that fueled late night drives from the East to the West, families and teachers and factory workers and migrants rolling in long caravans into the promise of the Rockies and the Pacific. Immigrants came because of the good jobs. They walked out of their houses, into the union hall, and came out with a pension. The Midwest was a cradle, a place to settle down, to learn a new language and a new way of life.

I’m reminded of a story a friend’s grandfather told us about his mother. She came over from Poland with her father and older sisters in the late 1800s and settled in the Ohio Valley. The father looked for work but was sickly and failed to find it and one day, without preparation or explanation, he left to go back to the motherland, leaving the girls – 15, 12 and eight – alone in an apartment they could not afford. The oldest girl began to work as a seamstress while the youngest ones went to school and they made extra money doing laundry and sewing. The three girls thrived in this new land, despite the odds and despite their father. They never saw their parents again.

Like seeds sown on good ground men and women who came to the Midwest did well for themselves. The Midwest was a cradle of greatness. It kept genius safe at its beautiful old schools and it nurtured creativity in its cheap garrets and vibrant streets. It taught millions the right way to live, to read, and to work. And, for a while, it looked like it could change the world.

That’s no longer the case.

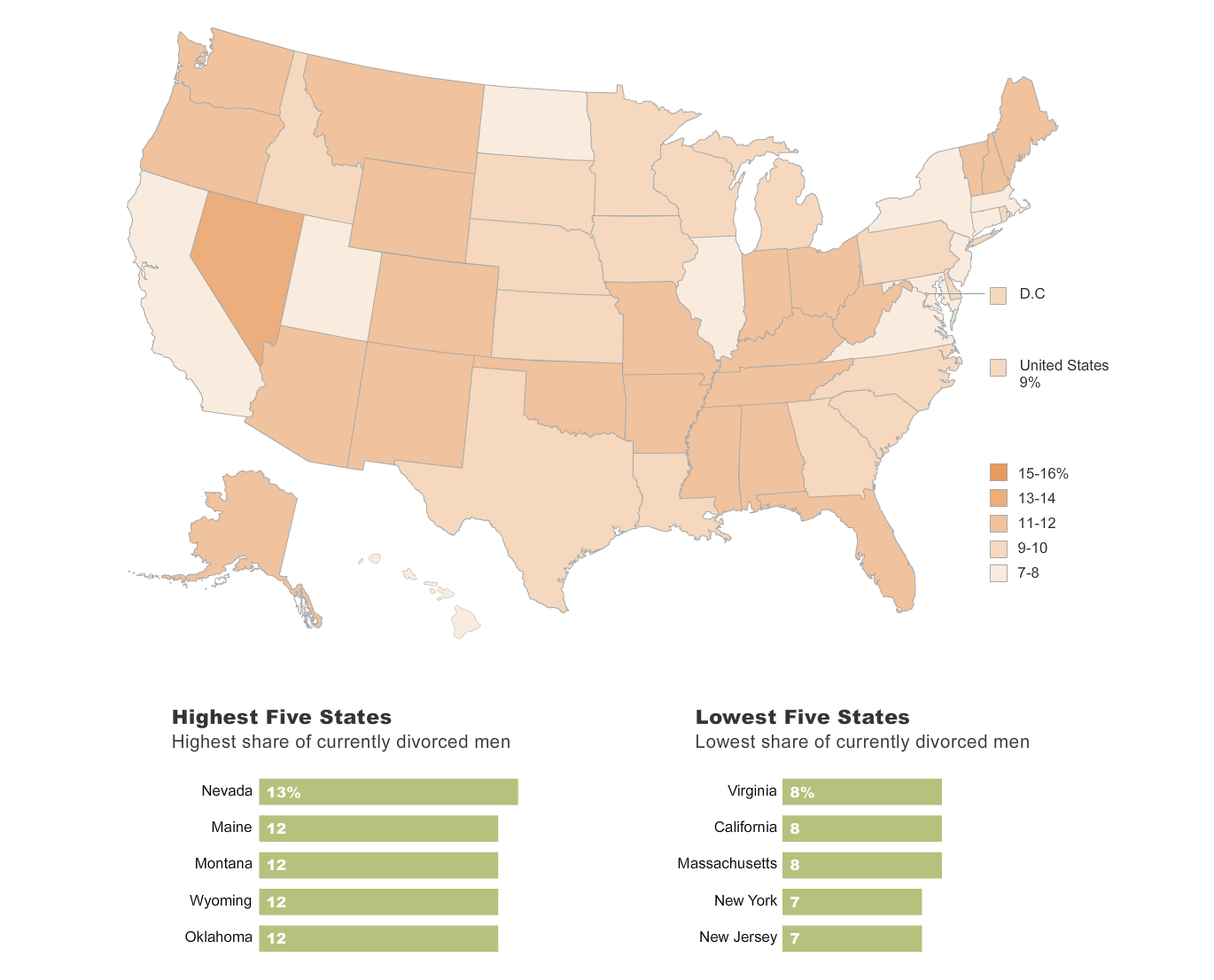

Divorce is endemic. The middle states are known more for drug trafficking than anything else. The smaller cities are at once segregated and gutted, creating pockets of poor families in the city center and a ring of rich families past the interstate escaping the blight. How did the old saying used to go? “New York is great to visit but I wouldn’t want to live there.” The same is now true of Topeka, of Grand Rapids, of St. Louis.

I worried about this. I wanted to see it again, to see what was happening in the states no one visits except to drop in on relatives at Christmas. The common narrative is that these are places that are now hollowed out and hopeless. I was reminded often of J.D. Vance’s fascinating work, Hillbilly Elegy, a book that shows what is truly happening in places like his hometown, Middletown, Ohio. These are the places that newspapers either ignore, admonish, or laugh at. They are backwaters full of uncultured and unlettered men and women, or they’re a tragic victims of globalization. They have no coffee houses or art theaters because, as Vance notes, there’s no one left to drink the lattes.

“Efforts to reinvent downtown Middletown always struck me as futile,” he wrote. “People didn’t leave because our downtown lacked trendy cultural amenities. The trendy cultural amenities left because there weren’t enough consumers in Middletown to support them.”

Replace Middletown with any other Midwestern hamlet and you get the same result. Morgantown. Toledo. Ferguson. Crystal City. They’re all interchangeable but they’re all broken in their own way. Slowly, however, life is coming back and I wanted to see those shoots popping through the bare earth.

The dreamer is stirring.

To come here again, to give it some time, was important to me. So we drove west from the Eastern shore like so many before us.

Columbus stockade blues

Our first stop was Columbus, Ohio, the city where I was born. Columbus is a college town and holds over 65,000 students on campus at Ohio State. It’s an engineering and agriculture hub but the school – and city – have a vibrant arts scene and a true startup culture.

The perfect avatar of this cross between art and commerce is Drive Capital, a boutique investment fund situated at the mouth of the Short North Arts District. They pay lip service to investing in Columbus startups and they have invested in a few over the past years, but they are there to be poised for a renaissance, not catch a wave.

In the 1980s the Short North was a haven for proto-hipsters and artists. Small storefronts held mini galleries and a monthly gallery hop was the thing to do for folks with a penchant for wine. The entire district – in fact the whole of High Street – received a full makeover in the intervening years culminating in the rise of multiple modern brick and steel buildings plunked down where dive bars and poetry bookshops used to be. The High Street of old, an amalgam of the aforementioned dives, convenience stores and head shops is gone, replaced by a modern walking mall. While I miss the stalwarts (the loss of Monkey’s Retreat, a comic book store, and Stache’s, the bar a friend and I played in at 16, are particularly saddening), I do enjoy the current crop of restaurants and coffee spots along with a massive and beautifully appointed student film center that shows first run and art films. The only place to get that fare used to be a few miles out of town at a theatre that had seen better days.

I asked around and even held a meetup in a bar while I was in town in an effort to meet some of the local talent. There was plenty. Most of it appeared to be in the tech service industries but there were definitely a few oddballs. One team presented an electronic musical instrument that worked like a theremin cross with an air guitar. Another, called Panopticon Labs, focused on keeping gaming honest. Theirs was a culture that was built on serving big clients, akin to the Central European startups that grew out of software houses but it also has engineering talent that rolls in from the school. Further, many of the startups aren’t tech at all yet still follow the tech VC trajectory. The locals agree.

Web Smith, for example, is a fixture in the Columbus scene. He’s an “e-commerce consultant” and is currently commuting between the heartland and New York. He’s seen innovation flourish in business that wouldn’t be considered startups in the technology world.

“Columbus has a disproportionate number of companies that began as small businesses and developed into VC funded, P/E funded, or cash-flow positive, high-growth brands. Jeni’s, Rogue, Startups.co, Homage are but four examples. Hot Chicken Takeover is the next company to achieve a similar trajectory,” he said. “These are real businesses that have avoided incubators and the spoils of prototypical startup culture. This is what Columbus is great at fostering.”

But all is not hot chicken and roses. Smith doesn’t recall a recent round of institutional funding. He estimates that most investors threw in “$100-200K” in the last few months while other companies have taken Ohio Third Frontier loans as part of a state-run project for small but growing startups. Ohio is also about to have a bustling medical marijuana market.

Across the country, cities like Columbus are thriving while cities where manufacturing found purchase are failing.

“The low cost of living along with the abundance of high-paying jobs is one great draw. I would also say that the city as a whole is truly trying to stay on the cutting edge,” said Dylan Gale, CTO Nuvestack. “There is apparently much more investment in Ohio than what I was aware of, although they are largely looking for fairly investor-heavy terms and many will have startups move out West if they become successful.”

But he’s also worried.

“I feel that the Midwest itself may be in for a bit of a downturn in the next 30 years. Some of the cities that were decimated as part of the rust belt have not returned to their former selves and may never do so. Many of the cities that did recover have grown with largely middle level IT jobs which are being automated and those are slowly going away,” he said. “I do actually worry that there is no direct path that many high-level engineers took in the IT world anymore. So many of my peers started out shaking the printer toner and worked their way up. I am not certain the middle-level jobs will always be around as stepping stones to get to higher levels. Too many things work the way they should from the start to require learning and innovation. It is also very difficult to take someone straight out of school and teach them higher level infrastructure knowledge without a solid understanding of the basics.”

What is happening in Columbus is at once unique and commonplace. Across the country, cities like Columbus – college towns, towns anchored by a hospital or a military base or finance – are thriving while cities where manufacturing found purchase are failing. Columbus is on the upswing while traditional manufacturing towns are in a gully.

A word on that. I tried for this piece to talk to some factory workers but they were hard to find. A friend’s son took a loading dock job because it paid well and imagines that his life could be different with a bachelor’s degree. Another man, a friendly carpenter who befriended my parents named Justin Giglio, sells and installs cabinetry now, a job that gives him great freedom, although he used to work in a cabinet factory. He says innovation without capital and support is sometimes foolish.

“Innovation is tough. Example: I can make a template/jig for my carpentry work, but what is the break even point? Will I be further ahead if I just continued the work without the template/jig? And it’s not like I have a 5 year contract for my work, so I may make the jig and then the work dries up. Then I made a jig for nothing.

“I have only lived in the Midwest, so I can’t compare and contrast,” he said. “Lots of people can build cabinets, but not a lot can sell them and prospect.”

Sadly, the return of manufacturing to the heartland, at least the kind that once supplied the tens of thousands of Midwesterners a steady job, a home, a pension, and sometimes a fishing boat, is dangled in the press as a sort of panacea, as if Armco or Wheeling Steel would come rumbling back out of the hills to save the day. In Columbus the Marysville Honda plant supplies an estimated 4,200 jobs but most of those are skilled engineering jobs taken by OSU grads. That plant, a bright spot in the Midwestern manufacturing firmament, will soon be joined by a $53 million Honda investment… in a massive data center.

The good jobs, the union jobs that gave a high school graduate or a new immigrant a nice house with a picket fence and their kids a good education, will never return. But a new generation is driving down the road to Honda’s data center and getting all that and more.

Don’t believe me? The best example is the tale of Vollourec in Youngstown. This French company is one of the largest manufacturers of steel tubing used in oil and gas mining in the world and, in a generally feel-good effort, they opened a new plant in an abandoned mill near Youngstown. Instead of tens of thousands of jobs, however, the mill hired 400 to manage their automated factory and when gas prices fell in 2015 the company laid off workers when demand for fracking materials fell.

This cycle – boom and bust – is exhausting, and folks in Rust Belt towns remain hopeful. Youngstown Mayor John A. McNally, for his part, kept his chin up.

“It better turn around,” McNally said in an interview in the local paper. “It’s got to turn around so Vallourec can put people back to work. It’s just a matter of when.”

Youngstown has embraced the new manufacturing. It’s a city of makers now, and micromanfacturing and 3D printing seem to be taking root in the town. It’s another rare bright spot in a seemingly cursed economic environment. But these years of confusion and insecurity are taking their toll in many ways.

We drove on.

Darkness at the edge of town

My friend E (not her real name) lives outside of Toledo, Ohio. She and her husband own a huge house on a few acres of land and they keep a horse in the stables down the road. E is highly educated – she has a PhD and her husband works for a tech company and is on the road a lot. Their house is bucolic in the summer. Tall trees surround an empty field and the two-story dream home with a big garage and stocked wine cellar. You turn down a long, winding drive to get to their garage. When we pull up we can’t see the garden in the failing light, but the air is redolent of the scent of newly ripe tomatoes and fresh-cut grass. In the kitchen they have a mess of heirloom peppers that they are using to make homemade pizzas.

They have the kind of house I dream of as a Brooklynite. Quiet, big, rambling, full of books and fun. Her husband brews his own beer and distills spirits. They have a well on the property and try to remain self-sufficient. Their daughter goes to the private school outside of the city.

When we pull up to her door she takes us to the stables and then we sit down to talk for a bit. There is an undercurrent of unease. She tells us about her daughter’s school and the feeling of educational isolation she experiences. She’s a little afraid and I wonder why.

Much has been said about the slow death of the American Midwest. Swathes of beautiful, fertile land have been given horrible monikers – the Rust Belt, the Meth Belt, and, more innocuously but insidious in its own way, the Bible Belt. This is one of those places, suggested E, a rusty shell housing an angry populace.

Toledo is one of those hollowed-out cities that you hear so much about. It was and is beautiful. Long avenues are lined with Victorian-style homes built when the Miami and Erie Canal began its meander along the lake. Later it was a stop on the New York-Chicago line, an artery of life and commerce that was shut when the highways bypassed the Northern Ohio cities and the railroads stopped carrying passengers to fill the city’s hotels, restaurants, and bars. Now it has a population of 285,000 and is renowned for its green energy efforts and artistic resurgence.

But high-tech and art museums don’t turn a town around. These societal perks give citizens a leg up when their schools are already running properly. They offer internships and quiet retreats for study and contemplation. They offer a nice trip on a rainy day for a class already primed to appreciate a solar plant or a Gauguin painting. But when there is little impetus to visit them they lie dormant, like Christmas decorations waiting for a better season.

Toledo’s public school systems are, by any standard, sub-standard. Except for outliers on the edges of town, most of the inner city test scores are poor, and suburban parents rarely send their kids into town to school. E’s daughter is one of them.

“I think Toledo will turn around eventually. We need to have jobs for interesting people that will make them enough money to survive. The downtown is beautiful and starting to turn around. Unfortunately the University of Toledo is not doing well, so scholars don’t choose to come here easily,” she said. “There’s a lot of peace here, and they are good people, although our interests sometimes diverge. It’s intellectually lonely. It’s not just Toledo though. Had a conversation with a guy my age in Oklahoma City going through the same thing. He loves the area, but misses people who think big thoughts.”

The educated feel isolated and afraid in the deep country where their neighbors might not share their citified views; those in small towns see danger in every tinted window and coastal license plate.

Further she is afraid of the militias. Over the border Michigan the Lenawee Militia is active and makes the political conversations E has with neighbors often overtly conspiratorial. She’s called “elitist” for using three-syllable words.

“Personally I think it’s going to get worse first. The divide between urban and rural will get even worse until we can have a major overhaul. I see the same thing in our education system. Until we completely reform it we are perpetuating our problems, and generations of people compare their own experiences to what is now and see change as bad.”

“Change is hard and painful,” she said.

There is a contrasting view of threats coming from cities to the country and vice versa. It’s the classic Deliverance/Clockwork Orange dichotomy. On one hand the educated feel isolated and afraid in the deep country where their neighbors might not share their citified views and, on the other hand, those in small towns see danger in every tinted window and coastal license plate. The dream of the city intellectual that was defined by the exodus from city to country after the Summer of Love is just that – a dream. Interesting many I talked to hoped that Google or Facebook or Uber held the answer.

In many small towns what they wanted as a big Google campus. It could even be run by a few dozen people and because workers were cheap and utilities would be cheaper they could set up shop, churn out code or run servers, and maintain some of the economy through tax payments. It is a sort of economics by cargo plane. A big company swoops in, deposits its offices, and swoops out.

For this to work, however, children like E’s daughter need to stay in the small towns after the graduate. E admits that that probably won’t happen. She stays in her community because her daughter can ride horses and go to a good private school. The rest of the intelligent teenager’s accoutrement – movie theaters, poetry readings, places to hang out – are missing.

“Those that embrace that intellectual freedom?” said E. “They head to the bigger cities with the better jobs and the greater number of people who are like them.”

That seems like the common sentiment among folks I talk to out here. The kids don’t want to stay and if they do there’s little for them to do. You have no opportunities in a very real sense. There is no opportunity to be educated, no opportunity to imagine a life outside of town. There is no opportunity to meet people with opposing viewpoints nor an opportunity to learn about alternative views. In the end, it’s a cul-de-sac masquerading as a town.

E is happy where she is. She loves her family and she loves her home and the stables and the school. She wants more but she knows she’ll get it, eventually. Not many in her town can say the same.

Bowling alone (in VR)

Two cities that we truly loved on our trip – Indianapolis and Cleveland – had undergone renaissances in the past decade that turned them from strange outposts on the road West to major cities in their own right. But there was a feeling in these beautiful towns of separation and segregation. Chicago is the colossus in this area and seems to have an outsize effect on the surrounding burgs. It draws young people out and away. You can grow up in Indianapolis but you work in Chicago or LA or New York. Your family still lives in Cleveland and you remember it fondly but you wake up in the fog of San Francisco.

Places like Indianapolis can also bring them back, but only in rare cases. When we visited, the downtown area was full of young professionals working at Chase and living in converted lofts in an old hotel. They had everything they needed, including a mall and plenty of places to drink. It’s a facsimile of nearly every minor metropolitan area I’ve ever visited: a place for the young professional to start in and then leave, a place where established folks can buy a house on the outskirts and live comfortably, disconnected from the urban core.

Aaron Perlut wrote this about St. Louis but it is applicable in all of the cities I visited. “St. Louis isn’t perfect — the local style of pizza is horrendous, our NFL football team should not be playing in a dome, the airport is an embarrassment, and the traffic lights aren’t timed. More important, we still struggle to create, attract, and retain more skilled workers. It’s an old-time, Mississippi River-based manufacturing economy that’s yet to fully reinvent itself that last year lost 14 percent of its professional services companies (law firms, architects, ad agencies),” he said.

“Without question, St. Louis does not suck. But with the exception of one very smart tourism campaign developed by the CVB, we typically do a terrible job of externally articulating what those offerings are. Perhaps by stepping out of our comfort zone, moving beyond silly turf battles, and developing a comprehensive approach to marketing the area, St. Louis can better promote a region that has much to offer.”

Further, there is little connection between the young people at the city center and the older ones (with money) on the periphery. The networks have broken down and there is no version of the Palo Alto-San Francisco cash corridor in these smaller towns. The problem, wrote Robert Putnam in his excellent book, Bowling Alone, is old timey, back-scratching, aka reciprocity.

Sometimes, as in these cases, reciprocity is specific: I’ll do this for you if you do that for me. Even more valuable, however, is a norm of generalized reciprocity: I’ll do this for you without expecting anything specific back from you, in the confident expectation that someone else will do something for me down the road. The Golden Rule is one formulation of generalized reciprocity. Equally instructive is the T-shirt slogan used by the Gold Beach, Oregon, Volunteer Fire Department to publicize their annual fund-raising effort: “Come to our breakfast, we’ll come to your fire.” “We act on a norm of specific reciprocity,” the firefighters seem to be saying, but onlookers smile because they recognize the underlying norm of generalized reciprocity— the firefighters will come even if you don’t. When Blanche DuBois depended on the kindness of strangers, she too was relying on generalized reciprocity.

A society characterized by generalized reciprocity is more efficient than a distrustful society, for the same reason that money is more efficient than barter. If we don’t have to balance every exchange instantly, we can get a lot more accomplished. Trustworthiness lubricates social life. Frequent interaction among a diverse set of people tends to produce a norm of generalized reciprocity. Civic engagement and social capital entail mutual obligation and responsibility for action. As L. J. Hanifan and his successors recognized, social networks and norms of reciprocity can facilitate cooperation for mutual benefit. When economic and political dealing is embedded in dense networks of social interaction, incentives for opportunism and malfeasance are reduced. This is why the diamond trade, with its extreme possibilities for fraud, is concentrated within close-knit ethnic enclaves. Dense social ties facilitate gossip and other valuable ways of cultivating reputation— an essential foundation for trust in a complex society.

This is exactly correct. There is no Midwestern network, not central spot where startups can gather. I’ve visited Chicago multiple times and, excepting a few rare examples, the startup ecosystem is closed and seemingly moribund. The same can be said of Columbus or Cleveland or St. Louis. To say this is tantamount to sacrilege and I know there are plenty of people in each of these cities trying hard to unify and create rather than separate. Each of these towns has its own incubator and accelerator, each has its own meetups. But there is little cross-pollination between cities, and when one company fails the only way out is back into corporate American from which many founders ran in the first place.

These cities are desirable. They call to us urbanites.

Flying over these cities on my way to some soiree in San Francisco or Seattle I wonder what life is like down there in a little town nestled at a confluence of rivers surrounded by farms, grasses blooming emerald in the spring and turning auburn gold in the fall. I imagine broad sidewalks that all led to the well-stocked public library. I imagine streets empty after eight except for a car full of summer-tan teenagers joyriding past my grandmother’s house and a cloud of dust. I imagine the calm feeling of a little town where everything is in its right place, where the market and the toy store and the penny candy shop are all in walking distance.

If the smart people in these cities got together and made it easy for Google or Microsoft or Facebook to open an office there, imagine the improvement to the downtown core. If a data center sprung up in a cornfield or a factory full of humans, and robots popped up in an old brewery, what could that change? For one it could bring back that promise of the Midwest in a way that we haven’t seen since 1975. It brings back the dream of a job, a pension, and a future. It’s not everyone’s future – you have to be educated to partake.

That’s the hardest lesson to learn and the hardest part of this. To become educated in Toledo or Indianapolis is to see places outside of Toledo or Indianapolis. And those places give you more money and prestige and the old little towns are left barren. That has to change.

Car tires on a gravel road

In my dreams of Ohio it is always summer. Heat rises in the cicada-riven night and darkness falls as patchwork lights plink on across the Ohio Valley. The moon sails over the river and reflects off the dead glass of the Wheeling Steel plant. A lone car passes my grandmother’s house on 8th Street and sometimes I hear a loud radio playing – something country, something 1970s – blasting on a stock stereo system. Sometimes a bottle pops on the curb and someone howls, the howl dopplering away down the lane. Our street light turns on and I hear the next-door neighbor, a widow who drinks, singing loudly, her voice unintelligible.

I dream of my grandparents. Sadie was a seamstress who worked at the glove factory in town. The glove factory is gone. Herman was a soldier who stormed the beach at Normandy and came back full of whiskey and quiet. He worked at the steel mill making galvanized buckets. That mill is gone. I dream of him on his old rocking chair listening to the ballgame on AM radio, late in the night. That AM radio is gone. His rocking chair still sits in my sister’s house.

She smiles openly. Herman never smiled.

In some of the dreams I’m talking with my grandmother about the future. I show her my Atari 800XL and she nods politely, unsure what I’m on about. She lives on a pension that lets her supply me with NES games and chicken patties and she has close friends up and down the block. That pension is gone. The friends are gone.

I dream I’m heading back to Martins Ferry after visiting DiCarlos pizza in Wheeling. I’m sitting in my father’s Ford Fairmont station wagon. The moon is riding along with us and I try to touch it with my finger. Then I dream I’m back there but it’s present day. I’m not young anymore. Everyone is gone. The only thing left on 8th Street today is the house and the streetlight. The relatives are gone. The warm feelings are gone. The streetlight reflects fear and forward motion and sadness and loss and gain. And out of this dream I wake blinking in a Brooklyn dawn longing for what was and what will be.

But I can’t have what once was and neither can the Midwest.

We must do better for the cradle of our union and it must do better for itself. It must start by dumping what it learned during its last boom. This information is dead, as dusty as the machinery that ground to a halt 40 years ago.

It is not an era of the singular man in the arena. It is the era of the tribe.

“I wish I could say that racism and prejudice were only distant memories. We must dissent from the indifference. We must dissent from the apathy. We must dissent from the fear, the hatred and the mistrust…We must dissent because America can do better, because America has no choice but to do better,” wrote Thurgood Marshall. While he spoke primarily for civil rights I think he speaks for America now. We must dissent from ignorance and anger and hate. We must dissent from forces that aim to pull us back and hitch our wagon to stars that pull us up.

I’m reminded of this excellent post by Patrick Thornton. He, like me, grew up in rural Ohio and says what’s true: that the good old days are gone but new days are coming.

“I have friends and acquaintances who are Trump supporters. They genuinely do not understand today’s shock, particularly from minorities. These Trump supporters do not understand that many minorities believe the people who voted for Trump endorse his racism and bigotry — that those voters care more about sending a message to the political establishment than they do about the rights and welfare of human beings,” he wrote.

“And, of course, people on the coasts could stand to meet more rural and exurban people, to understand why they are anxious about a changing world and less economic opportunity. But rural and exurban people need to see more of America. People do not understand the depths of how little rural America travels and sees other people and cultures. I’m from the Midwest, and I love the Midwest, but it’s not representative of modern America. We cannot fetishize it as ‘real’ America. It’s part of America — a great, big, beautiful, messy republic — but just a part.”

We are hurtling into a future of self-driving cars that will leave millions jobless. We are hurtling into a future where the only exploration will be interplanetary and we will need strong men and women who aren’t afraid to work as we leave this planet. We are hurtling into a future where we all have to get smarter, closer, and more-connected to win. It is not an era of the singular man in the arena. It is the era of the tribe. There are few compromises that can be made for the ill-prepared and few remedies for those who believe they deserve them.

The dreamer is stirring. What will it see when it wakes?