To land a press interview with Brogan Bambrogan, the former CTO of the transportation startup Hyperloop, who is now suing the company over breach of fiduciary duty, you must first receive the blessing of Sitrick & Company, a 28-year-old, L.A.-based public relations firm whose other clients have included the wearable tech company Jawbone, the board of vegan food startup Hampton Creek, and the diagnostics company Theranos.

It’s easy to appreciate why Bambrogan hired the firm to filter media inquiries. When it comes to handling crisis situations in particular, Sitrick is as well-regarded as they come. Its approach, neatly captured by its tagline, is: “If you don’t tell your story, someone else will tell it for you.”

“We’ve been in a tricky position a number of times and the thinking [in Silicon Valley] has historically been to ignore [reporters],” says one Bay Area tech founder who has hired the firm but who asked not to be named in this story. “Sitrick takes a very opposite approach. You’re made to get into the trenches and engage. It can be a pain because it takes longer and you’re busy, but in many cases, the story is better and more balanced because of it.”

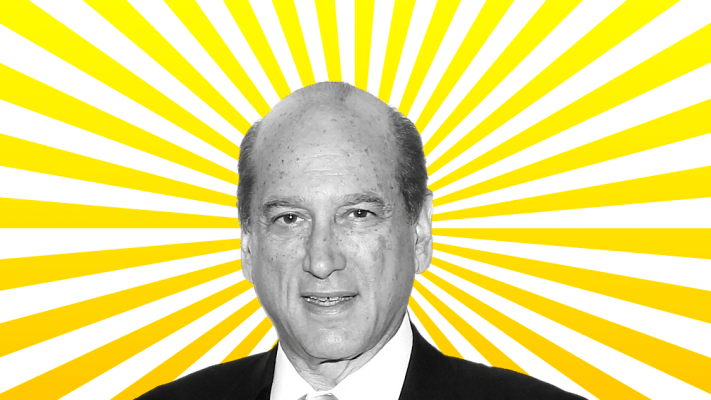

At the center of it all is Mike Sitrick, Sitrick & Co.’s 69-year-old founder and chairman, who flies a Gulfstream to far-flung meetings and runs the firm with the help of 14 partners, numerous associates, and what seems like a boundless amount of energy. (Though he suffered from a collapsed lung last year, his office subsequently sent a picture of Sitrick to a concerned New York Post reporter, assuring her that he still starts his morning with 150 push-ups and 150 sit-ups.)

“He’s usually one of the first people into the office and one of the last out,” says an employee who spent more than a decade with the firm and has since joined another communications outfit so asked not to be named. “It’s such an impulse to say, ‘No comment, I don’t want to be part of a story,’” says this person. “Mike is all about providing context so reporters understand the point of view of the company that Sitrick is advocating for.”

To make those connections easier, Sitrick & Co. — which employs 50 employees and signs up roughly 250 clients each year — recruits top journalists from esteemed outlets. Among the firm’s current employees are Sallie Hofmeister, a former assistant managing editor at the L.A. Times; Seth Lubove, a former Bloomberg bureau chief in L.A.; and Wendy Tanaka, who was once the Bay Area bureau chief for Forbes.

Says Sitrick, “I keep hiring journalists because it’s easier to teach them what PR does than teach PR what journalism does.”

Spinning a yarn

Some might call what these employees do – putting the best face on hostile takeovers, plant explosions, sexual harassment claims, and earnings disasters, among other things – straight-up spin. In fact, Sitrick authored a book by that title in 1998.

Yet well-heeled clients — who pay $1,000 an hour, plus a retainer — insist that it works.

One of them is Stan Gold, a former lawyer who runs Shamrock Holdings, an investment vehicle for members of the Roy Disney family. Gold engineered the hiring of Michael Eisner into Disney in 1984, and by 2004, he was leading the fight for Eisner’s ouster as Disney’s CEO. He largely credits Sitrick for making that campaign successful.

“Mike is always on the case,” Gold says. “He’s your first call at 6:30 a.m. He’s already read the wires and he’s got ideas and he’s at your door at 9 a.m.” With Eisner, Gold explains, “We didn’t have a way to communicate with all of Disney’s shareholders, so Mike got it out in the WSJ and the Financial Times that we had put together a site, SaveDisney.com, and through that site, we were able to influence [those stakeholders].”

Lance Etcheverry, a litigation partner with the law firm Skadden Arps in L.A. who has worked on the Hyperloop case and with Jawbone, similarly sings Sitrick’s praises.

“A number of times, where either something was about to happen in litigation or I’ve needed something to run on the front page of every major newspaper out there, I’ve put down that kind of directive to Mike and he’s made it happen.” Etcheverry acknowledges that most have been high-profile matters where a lot of attention was already being paid to them. Still, he insists, “I’ve never seen someone who can make things happen on that kind of scale.”

Things don’t always work out as smoothly as Sitrick might like. He recently began representing billionaire Vinod Khosla in his long-running legal war over public access to his coastal property, Martins Beach, in California. The situation has been an ongoing public relations disaster for the famed venture capitalist, and a new lawsuit filed by Khosla, one that observes that no other coastal property owners have been subjected to similar scrutiny, hasn’t changed critics’ minds (despite a Forbes piece last month that laid out his case).

According to a source, Sitrick also represents Michael Goguen, a former partner at Sequoia Capital who was named in March in an extraordinary breach of contract lawsuit that accuses him of sexually mistreating a woman he met in 2001, then refusing to honor a financial arrangement they’d made in more recent years to keep her from suing him. Though the lawyer for Goguen’s accuser abruptly asked to withdraw from the case, which is scheduled for trial next year, Goguen remains persona non grata in Silicon Valley for now.

Crisis close to home

Sitrick & Co. had bad publicity of its own to overcome in 2010, when, after selling to a professional services firm called Resources Connection (Sitrick is now run as an independent subsidiary), it was sued by a former employee for undervaluing its employee stock option plan. Sitrick & Co. eventually agreed to settle the case alongside a trustee for the plan, with insurance paying out roughly $6 million to the plan’s members.

Asked about it now, Sitrick sighs. “No good deed goes unpunished. Employees ended up making a lot of money through [the plan]. It was an additive benefit. But you do a business deal and not everyone will be happy. Unfortunately [lawsuits] are a part of doing business.”

Sitrick notes that most of his employees have been with the firm for more than a decade, a point confirmed in interviews with numerous current and former employees who describe a hard-charging but exciting work culture.

A Silicon Valley expansion

This is crisis communications, of course. Even when Sitrick works his magic, it’s not necessarily for the greater good, though he’ll convincingly argue otherwise.

The former employee who now works for a competitor proudly recalls Sitrick & Co.’s work with Metabolife, a San Diego company that made ephedra-based dietary supplements that became a popular way for its customers to lose weight. When in 1999, reports began to surface that the product might not be safe, the news program “20/20” asked to interview company founder Michael Ellis. Fearing the report would be slanted, Sitrick came up with what were two highly novel ideas at the time.

First, he made certain the interview – all 90 minutes of it – was filmed, and he posted the uncut footage on an internet site weeks before the program was aired on network television. Sitrick then paid for full-page newspaper ads and radio spots that raised questions about the sources “20/20” chose to interview, including a dietary expert who happened to be a paid consultant to Metabolife competitor SlimFast.

Owing to some last-minute editing by “20/20” and an interview with a happy customer, a story that could have doomed Metabolife instead prompted soaring sales in the weeks following its broadcast. In the ensuing years, however, ephedra-containing supplements were linked to strokes, heart attacks and more than 150 deaths, and by 2004, the FDA had banned the products.

Asked if Sitrick & Co. ever turns away clients because of what they represent or because they haven’t been candid, Sitrick says it has. “I’ve fired clients who aren’t forthright with me.” He suggests that he has also turned away potential business from people and companies whose situation is so grim, it’s not worth getting involved.

Indeed, Sitrick is an “intuitive genius,” argues Lew Phelps, a former WSJ reporter who recently retired from Sitrick & Co. after 20 years, and who says he has “seen Mike pull real rabbits out of a hat.”

One of Phelp’s favorite stories takes place in 2011, when the audio equipment maker Dolby, the firm’s client, was suing Blackberry for infringing on its patents and not paying to use Dolby’s compression technology.

According to Phelps, Sitrick convinced Dolby’s lawyers to include language that Dolby was seeking an injunction to “ban the import of offending products,” phrasing they were reluctant to insert but that dramatically ratcheted up the media attention and pressure on Blackberry. Says Phelps: “The idea of a lawsuit over who is getting paid how much isn’t a huge story. But the idea that nobody would be able to buy a Blackberry – which was still the gold standard of phones at the time — made it huge.”

Within four months, the two companies had agreed to a licensing arrangement, and Blackberry co-founder Michael Lazaridis was a Sitrick & Co. client.

Sitrick likes to think he brings the same resolve to current clients, a growing number of which are in Silicon Valley. As for why that is, he notes that it’s largely a numbers game. “More companies are experiencing problems because more money has been thrown into the tech industry, and when there’s more volume, you see both more successes and more failures.”

Sitrick compares the tech industry to the entertainment business, which has long been a high-profile if small part of Sitrick & Co.’s practice. (Among many past clients: R&B singer Chris Brown.)

“Both are very gossip-oriented industry, where you have a lot of chatter, a lot of interest from the public. And that’s only grown more intense as this enormous wealth has been created. Look at the intense interest in Theranos. Look at Zenefits,” the HR software company — and another former client of Sitrick. “If they weren’t so highly valued, who would be so fixated on their woes? No one.”

I ask how, over the years, Sitrick has managed the ever-shortening cycle between public outrage and resolution. Before jumping on his next call, Sitrick acknowledges there is a cycle, but he says his firm is mostly focused on another question, which is, “So what?”

Says Sitrick, “Reporters are taught to ask who, what, where, when, and why. Our job is to figure out what makes news and why something is important.”

After that, it’s time to “engage, engage, engage,” he says.