It’s been several months since Alibaba’s blockbuster acquisition of Lazada, the leading e-commerce platform in Southeast Asia.

When the news broke, pundits and critics debated whether or not each side got a good deal, how it would impact rivals like MatahariMall, Tokopedia and Orami, and how the region would be flooded with cheap Chinese products.

Elsewhere, startup founders and VCs high-fived each other as the move put the region on the global map and they hoped it would lead to more funding and exits in the future.

However, everyone has failed to go beyond superficial observations. Alibaba’s acquisition of Lazada is much more than simply growing retail GMV, proving exactly why Jack Ma is Jack Ma and why he’s always been several steps ahead of the game.

Those celebrating the news, especially those in the retail space, may end up biting their tongues.

Peter Thiel, PayPal and Why Distribution Matters

In his book ‘Zero to One’, Peter Thiel talks about how PayPal almost didn’t survive were it not for their lucky break stumbling onto what would become their biggest distribution channel, growth engine, and eventual acquirer: eBay.

PayPal focused on targeting eBay’s Power Sellers — those responsible for the bulk of volume going through eBay — and then amplified it by paying for user sign ups and invites to friends, effectively turning PayPal into a mainstream payments platform.

No wonder Peter Thiel has been such a fervent proponent of distribution, beyond just building a great product.

“Poor distribution — not product — is the number one cause of failure. If you can get even a single distribution channel to work, you have great business. If you try for several but don’t nail one, you’re finished,” Thiel writes.

eBay accelerated PayPal’s growth thanks to its reach and velocity of transactions — high usage kept the payments company thriving. Distribution is exactly what Alibaba needs Lazada for. But for what? Most definitely not cheap Chinese products.

Inside The Belly of The Beast

Around the same time that Peter Thiel’s PayPal was acquired by eBay, the latter company was attempting to grab market share in China through an investment into — and eventual acquisition of — EachNet in 2002, at that time the leading Chinese C2C marketplace.

In response to this, Alibaba launched Taobao in May 2003 and eventually beat EachNet to become China’s largest consumer-to-consumer e-commerce marketplace. In a timespan of 3-4 years, eBay’s C2C market share plummeted from 72% to 8% and caused them to throw in the towel while Taobao’s share continued to climb, reaching over 80% by 2007.

Shortly after Taobao’s launch, Alibaba introduced Alipay, a third-party online payment platform, in 2004 to help facilitate transactions on Taobao. Today, Alipay is China’s largest third-party payment platform with 70% market share, boasting over 400 million users and generating over 80 million transactions per day (compared to PayPal’s 9 million).

Whereas PayPal was primarily a peer-to-peer (P2P) online payments platform based on email and linked to credit cards, Alipay was connected to bank accounts and incorporated features tailored to the Chinese market, such as escrow services.

According to Jack Ma, Chinese culture, despite being one that traditionally values trust and integrity, lacked a system that enforced it. As a result, Alipay’s escrow feature was a perfect solution to the trust gap and shifted China’s e-commerce behavior away from cash-on-delivery (COD) towards one that is seeing 68% of transactions today.

With Taobao’s massive reach and distribution — 423 million annual active buyers and over 90% of total C2C ecommerce GMV in China — Alipay was able to cement its position as the leading third-party payment method.

Leveraging its 400 million users and reach through Alibaba e-commerce platforms, Alipay has grown beyond being an Internet-based payment platform into a finance and banking behemoth to the extent of threatening the old financial guard.

In 2011, Alipay spun off Alibaba to become Ant Financial Services Group, covering everything from online payments to microlending to banking and credit scores. Based on its recent funding round of $4.5 billion earlier this year, the group is now valued at $60 billion, making it the second most valuable non-public tech company behind Uber.

With this new war chest, Ant Financial looked to expand into new markets and for a while had been trying to get a foot into Southeast Asia. The company set up a Singapore entity as early as 2010 but lacked a proper distribution channel. Ant Financial’s lucky break seems to have arrived earlier this year.

Eyeing The Payments Opportunity in Southeast Asia

In many ways, Southeast Asia e-commerce is like China e-commerce but 8 years younger. Back in 2008, cash-on-delivery (COD) was still the dominant payment method in China making up over 70% of payments. Today, Southeast Asians rely heavily on COD when shopping online, attributing to roughly 70% of transactions.

To wean customers off a high dependency on COD, many well-funded startups and established conglomerates have been trying to solve the payments bottleneck, including Omise (Thailand), Doku (Indonesia), LINE Pay (Thailand), and True Money (Thailand).

Despite the PR and media hype, these homegrown solutions have yet to shift consumers away from COD because a lot of these heroic efforts have been “technology for technology’s sake” — building a faster car when what is really lacking are more roads

The Product Challenge

- Platforms like Omise and 2C2P are basically payment gateways and don’t offer a viable solution for the massive C2C and P2P space that Google and Temasek peg at ‘several billion dollars’. These payment gateways still primarily process credit cards and, with credit card penetration across emerging SEA standing at single digits only, doesn’t really address the core of the issue. In addition, these solutions do not offer a fix for the trust issue often hindering C2C and P2P transactions — namely escrow.

- 2C2P and Omise also face getting ‘pushed out’ as they don’t own any ties to the end consumer. Meaning if a cheaper and better alternative was to present itself, there is nothing stopping a merchant from swapping them out. Taobao got users to sign up to Alipay, making it much easier to convince non-Taobao e-commerce platforms to adopt Alipay as well.

- Rabbit LINE Pay, previously LINE Pay, never captured much market share despite its association with LINE, the popular messaging platform reaching 33 million users in Thailand. LINE Pay’s limitation is that it only supports credit cards, stumbling yet again into one of the fundamental payment obstacles in Southeast Asia – lack of credit card penetration.

The Distribution Challenge

- Although good attempts at providing shoppers with a second payment method, fintech startups like Digio and Deep Pocket are building mobile wallets before solving their chicken-and-egg problem.

- It is difficult for mobile wallets to become widespread when awareness is low and users don’t have a strong (often financial) incentive to adopt it. User acquisition then becomes an expensive play without an inherent distribution channel.

The (Lack of a) Use Case Challenge

- One of Thailand’s leading mobile wallets, Ascend’s True Money, connects with major banks in Thailand and has distribution access to companies in the CP conglomerate portfolio, including over 19 million mobile subscribers.

- Yet, True Money is reported to have as little as 100,000 active monthly users out of 6 million registered users as of 2014. True Money’s current use cases are limited to mobile phone top up, online game top-up, and bill and over-the-counter payment, typically at CP-owned 7-11 stores.

Ecommerce is a more obvious and natural use case and therefore True Money is also used as a payment gateway on Ascend’s ecommerce properties WeMall and WeLoveShopping. However, with only 26% of Lazada’s traffic, Ascend still has a long way to go before taking a page out of Peter Thiel’s playbook and turning its ecommerce properties into a fertile breeding ground for its payment solutions.

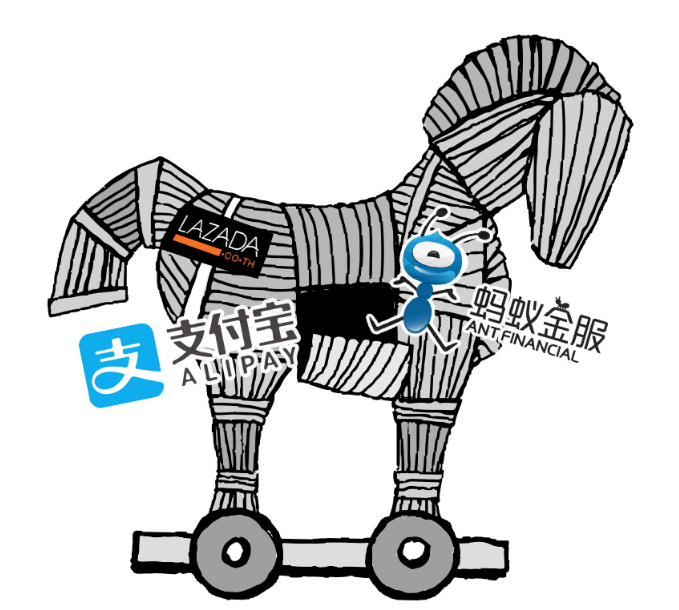

The Lazada Acquisition: A Trojan Horse Strategy?

Alibaba’s foray into Southeast Asia has never really been about growing retail GMV. In the long run, it’s not so much about beating Lazada’s direct rivals or tapping into new growth markets outside of China; it’s about securing access to a massive end user base in a market whose lack of commerce infrastructure is eerily similar to early days China. Jack Ma’s endgame is to introduce and monetize his other products and services, starting with Alipay.

Adopting Alipay would be pivotal for the region’s e-commerce growth and that of Lazada in particular. Widespread adoption of a convenient payment platform that bridges the trust gap between buyers and sellers will lead to more transactions overall as witnessed in China, now the world’s biggest e-commerce market in terms of GMV and penetration.

Alibaba’s (ironic) 20% stake in Ascend Money, the parent group of True Money, coming just a few months after the Lazada deal, shows Jack Ma’s master plan for Southeast Asia gradually coming to fruition.

But it’s much more than just Alipay and facilitating marketplace payments. As highlighted earlier, Ant Financial, Alipay’s parent company, operates an entire digital finance ecosystem in China consisting of but not limited to: Yu’e Bao, the biggest mutual fund in China in terms of investors with $108 billion in assets; Zhaocai Bao, a P2P lending platform with $32 billion in transactions in its first year; and Sesame Credit, a credit-scoring system based on — you’ve guessed it — ecommerce data.

And finance is only scratching the surface. Jack Ma, in his 2015 letter to shareholders, hints at much more to come:

“Alibaba group’s strategy is to build the infrastructure of commerce for the future. Ecommerce is only the first step. […] Around half of Alibaba Group’s workforce and our affiliated companies, including Ant Financial and Cainiao, are working on important areas of our ecosystem, including logistics, Internet finance, big data, cloud computing, mobile Internet, advertising and the so-called double H industries — Health and Happiness (the big data-based healthcare and digital entertainment businesses which will take 10 years to become data-driven).”

Hence it shouldn’t be retailers like MatahariMall or Central that should be worried about increased competition; instead, banks, insurers, hospitals and everyone else should start preparing for some ass whoopin’

For a preview of what could be coming up in Southeast Asia one only needs to look at what happened to Uber recently in China.

Learnings From China or How Alibaba’s Trojan Horse Strategy Killed Uber China

“Uber didn’t lose in China in 2016. They lost in 2014 when they got in, and found out 2 years later.” — Wang Di, Quora User

Alibaba, partnering up with long-time frenemy Tencent, adopted a similar strategy in China to take out Uber.

Outsiders often point to the classic textbook “why-foreign-Internet-companies-fail-in-China” excuses like lack of localization (culture/language barrier), lack of connections/guanxi, government protection, and lack of IP law enforcement. Although these do apply to a certain degree, none of them get to the core of why Uber failed in China.

Uber failed because it thought it was competing against Didi in the smart transportation space. Little did they know that Didi’s majority shareholders, Alibaba and Tencent, were playing according to an entirely different set of rules.

For Alibaba (and Tencent), Didi wasn’t just a ride-hailing app; Didi’s strategic and hidden purpose was to serve as a scalable user acquisition channel for Alipay Wallet, Alipay’s mobile version, as well as Tencent’s WeChat Wallet, according to this brilliant Quora answer:

Around 2012, WeChat’s super success helped many Chinese IT companies shift their focus to the mobile app market. Meanwhile, though with occasional suspensions, the government started encouraging mobile payment development. All was set for Tencent and Alibaba to launch their mobile payment app to be a booming big thing. All except for the Chinese user habits.

The Chinese were not familiar with mobile payment at that time. In fact, no large group of people in the world were significantly better than the Chinese either. Moreover, the Chinese were mostly quite cautious when paying online, and a lot of them are not exactly fans of novelty gadgets.

But how they love discounts or kickbacks! A dollar saved is a dollar earned.

The cab-calling apps Didi and Kuaidi became perfect for user traffic introductions.

Users could tap Didi to call a cab and pay 30 yuan in cash, but if they paid the cabbie by Tencent Wallet (redirected from Didi), they would only have to pay 10. Were users willing to save 20 yuan—3 or 4 US dollars—by using an already built-in feature in another app? Just a few taps here and there? Hell yeah.

And then they were hooked-up with WeChat Wallet. Which was what Tencent really wanted.

With Didi as a key distribution channel for Alipay Wallet, Alibaba was able to acquire more users into its ecosystem of services including Taobao, Tmall, Ant Finance and much more, leading to monetization across different products. Uber only had transportation.

Tencent and Alibaba have been throwing unthinkable amounts of money to pay for all the unbelievable kickbacks. Unthinkable for a cab-calling app, but totally reasonable if you want to mark your territory in the biggest market in the world that is most advanced in mobile payment.

What The Future Holds for Southeast Asia

With Southeast Asia being hailed as the next big and untapped ecommerce market in the world, we are seeing many players subsidizing their way into growth through discounts and coupons. Not surprisingly, critics often look at this as a race to the bottom for everyone.

Not entirely true. As the Uber China example has shown us, this will only be the case for companies that fail to look at the bigger picture and are unable to monetize through a diversified set of products or services, whether now or in the future.

With all this in mind, one could argue that Alibaba got a pretty good deal with Lazada, especially given the long-term opportunities in SEA beyond retail ecommerce. A quick look at Alibaba’s stock confirms this—Alibaba’s share price jumped after the April 12 acquisition announcement and has increased by 35% ever since (as of October 3, 2016).

Alibaba’s acquisition is widely considered a victory for the growth of ecommerce in SEA but how many of us here are ready to face the fact that whatever trophy we hauled in may not be a shiny unicorn but perhaps something else?