Those of us interested in marketplace lending have recently observed many pejorative headlines about P2P lending platforms. These headlines mostly reported on Lending Club’s recent difficulties, but also criticized other platforms and the P2P lending model more broadly. Very few people anticipated this kind of a problem less than a year ago as investors were competing for allocations on platforms.

More often than not, it has been very challenging to purchase loans, particularly on the more established platforms. Indeed, the limiting factor for the growth of volumes has been the lack of borrowers. Platforms have had to compete with each other and ramp up marketing expenditure in order to attract borrowers. Even the biggest skeptics of the marketplace lending sector would not have imagined the extent to which the situation would change in 2016. In Q1 2016, leading platforms significantly decreased originations (Prosper, 12 percent; Avant, 27 percent) — and this was only the beginning.

After Renaud Laplanche, the former CEO of Lending Club, had been dismissed, the loan amounts issued by Lending Club dropped dramatically: Q2 originations dropped to $1,955 million from $2,750 million in Q1 2016. Other platforms were hit even more significantly — Prosper originations dropped 50 percent YoY, from $912 million$in Q2 2015 to $445 million in Q2 2016.

However, after taking a hit, Lending Club stock was one of the best performers — climbing from a low of $3.51 per share on May 13, 2016 to $6.43 on September 16; that represents an 83 percent increase (compare that to 4.5 percent increase in S&P 500 Index). The market slowly understands that things are not as bad for marketplace lenders as reporters or bloggers mistakenly infer.

I personally believe there is one thing that is crucial for the success of the marketplace lending industry in the long run, and it is loan performance. Should investors get what they have anticipated, sooner or later money will flow into the industry. One can argue that in the long run we are all dead, and it is important that investors continue purchasing loans sooner rather than later for marketplace lenders to be sustainable.

In my opinion, there are few good reasons why investors will continue buying loans and we will soon see an increase in originations:

- The unemployment level is at its historic lows, which means the probability of loans being paid is high;

- Major marketplace lenders recently increased rates in order to attract more lenders to platforms;

- With a limited amount of money coming from lenders, and borrowers’ demand exceeding funding capacity of marketplace lenders, platforms are forced to stick to better borrowers (when you have a limited amount of capital, why should you prefer a weaker borrower to a stronger one?)

- As shown by Lending Club reporting, platforms pay incentives to investors to stimulate purchases of loans that further increase loan yields.

All of the above means that returns for investors in loans originated by platforms are likely to stay high. And high returns always attract those willing to take a risk. The key question in my opinion is “what is the risk that I am taking when investing in P2P loans and what indicators should I follow in order to try to predict what is going to happen next?” A lot is written about risks of investing in P2P loans, but what are the indicators to watch for?

In my opinion, the best proxy for P2P loan defaults is the credit card default rate. This is because a significant portion of loans originated by P2P platforms are used by borrowers to refinance credit card loans, with P2P platforms typically offering lower interest rates. While there is limited data available on the performance of P2P loans during recessions (though that data is positive for the marketplace lending industry), credit card default rates are available since 1985.

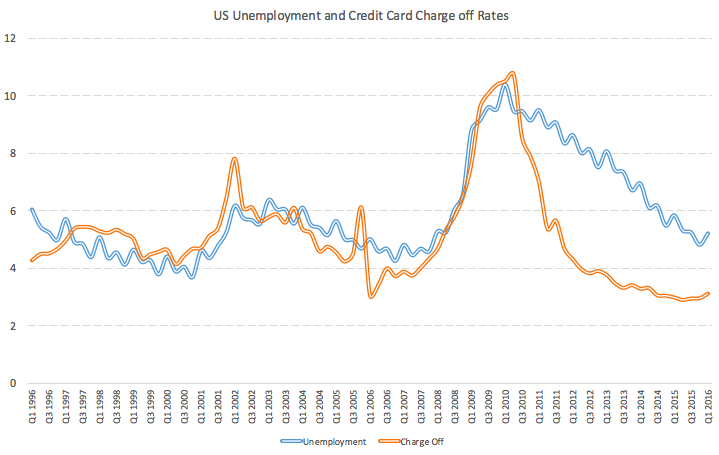

An article by Stephen Cecchetti and Kermit Schoenholtz analyzes the relationship between credit card default rates and unemployment rates. As expected, the article suggests a strong dependency — default rates are expected to increase by 0.55 percent for each 1 percent growth in unemployment. However, the regression described in the article also exhibits a strong autocorrelation, which can lead to incorrect conclusions.*

To evaluate the presence of autocorrelation, the Durbin Watson test is commonly applied. If the value of the test is close to zero, there is strong evidence of autocorrelation. Upon replicating the regression presented in the article, we found strong evidence for autocorrelation — the Durbin Watson test was equal to 0.16. The function of the regression is presented below:

Default Rate = 1.49 + 0.55 * Unemployment Rate

To eliminate the autocorrelation, we built a regression using the change in the default rate and the change in the unemployment rate (i.e. the first difference of the underlying variables) and we get the following function:

Change in Default Rate = 1 * Change in Unemployment Rate

This result indicated that 1 percent increase in unemployment is likely to lead to a 1 percent increase in default rates (not 0.55 percent as the article cited above states). In this case, the Durbin Watson test statistic is close to 2, meaning that no autocorrelation is present. However, the regression exhibits a rather low R2, indicating that changes in the unemployment rate only partially explain changes in the credit card default rates, and there are other factors that should be taken into account, as well.

The graph of the unemployment rate and the credit card default rate clearly demonstrates the relationship described by the regression above.

What does this tell us about the potential increase in the default rate if the U.S. economy experiences another major recession? The graph above demonstrates that the credit card default rate increased from an average of 3.53 percent in 2006 to 10.43 percent in Q3/Q4 2009 – Q1/Q2 2010, a 2.95x increase. Meanwhile, the default rate increased from 4.35 percent in Q2 1999 to 7.81 percent in Q1 2002, a 1.8x increase.

From these observations we can estimate that the default rate will likely increase 2-3x depending on the severity of the recession. Orchard Platform published a very good white paper that discusses potential consequences of such increases in defaults. Page 11 of the white paper states “In fact, realized defaults would have to be 2.2 times projected rates in order for a loss to be realized.” This gives a good representation of what to expect, and I strongly encourage those of you who are interested in understanding this topic in detail to go through that white paper thoroughly.

History tells us that the most lucrative investment opportunities arise during major capital outflows from the markets. Does investment in P2P loans bear significant risk? It certainly does, but I hope the analysis provided above sheds some light on that risk and key factors to consider — watch the unemployment closely and enjoy the return in the low-yielding environment.

*For analytics lovers: Autocorrelation is a common problem of regression analysis. It occurs when data sets change inherently in one direction, not because one variable depends on the other, but due to an external factor. The autocorrelation of regression residuals leads to poor estimation quality of the regression parameters and to overstatement of test statistics that are used to test the significance of coefficients.

Disclosure: Mike Lobanov is the general partner of Target Global, which is invested in Prosper, and a board observer in Prime Meridian Capital Management.