Exoplanets are the talk of the solar system this year, but as exciting as they are, their existence (as is often the case in astronomy) is more inference than direct observation. A new private effort known as Project Blue hopes to change that with a satellite built for a single purpose: to directly image an exoplanet in the Alpha Centauri system.

“There’s this confluence of scientific imperative with the exoplanet discoveries from Kepler, and the whole community being energized,” said Jon Morse, former NASA program director and leader of the project. “It’s plausible that there are Earth-like planets in Earth-like orbits around the two sun-stars in the Alpha Centauri system — and we’re going to go find out.”

To that end, Morse and his colleagues started the BoldlyGo Institute, a private space research firm. BoldlyGo is working on a few projects, but Project Blue is a collaboration with Alpha Centauri-focused nonprofit Mission Centaur.

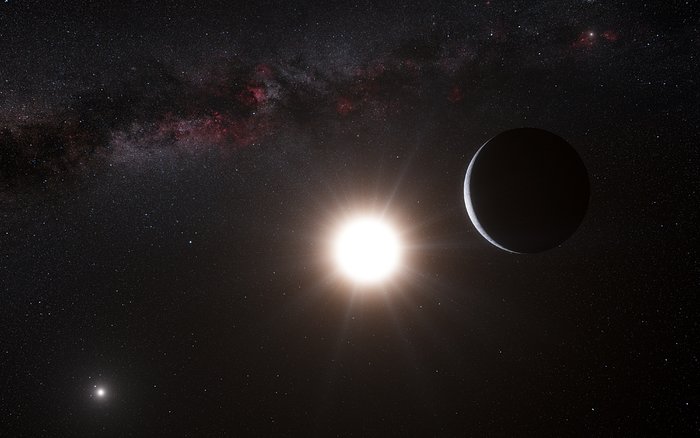

Recent surveys of space by Kepler and other missions have revealed that Earth-like exoplanets are actually fairly common, cosmically speaking. In fact, recent data already suggest there’s one in the Alpha Centauri system – but orbiting the red dwarf known as Proxima Centauri (and it too has a project dedicated to imaging it). Project Blue will be looking at the other, more sun-like stars there, known as Alpha Centauri A and B.

I can guess what you’re thinking: if we know the planets are there, don’t we just have to point something like the Hubble in that direction?

Turns out detecting planets is much easier than actually seeing them. And it’s still really hard! Even the closest stars are so distant that the strongest instruments we have available can barely detect them as single points of radiation — to say nothing of any planets they might have around them.

Morse compared it to trying to see a firefly while staring directly at a lighthouse – from 10 miles away.

But recent advances in an imaging technique called coronagraphy make it possible. Essentially, you have to very, very carefully block out the lighthouse.

“The coronagraph, the instrument type, goes way back,” Morse said. “It starts with observing the sun. When people discovered the corona, they did so by blocking out the disc of the sun so you could see faint things next to it. We’re borrowing that technique and applying it to blocking the light of another star so we can see a planet that might be a billion or more times fainter.”

The University of Massachusetts Lowell is one of the project’s partners; its scientists have been pushing the boundaries of interstellar coronagraphy. Test flights sent to the edge of space have demonstrated that coronagraph systems can successfully block out the light of a distant star, then make the minute adjustments necessary to their imaging and mirror systems to show surrounding objects. These prototypes will need to be improved by an order of magnitude, probably, but no one expected expanding the frontiers of astronomical observation to be easy.

With a general idea of the system and what type of object they’re looking for, they can narrow the search considerably — essentially they’ll look where Earth would be if it was in Alpha Centauri.

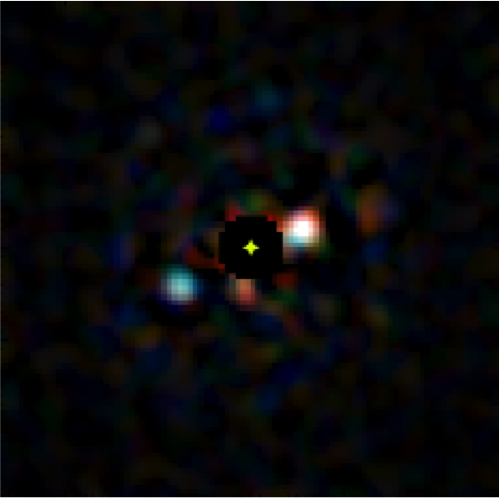

If it works, the results will be historic – though you probably won’t want to print them out. The planet itself won’t be much more than a handful of pixels. But oh, what pixels!

“We won’t resolve features on the planet. It will be a point source, a ‘pale blue dot’ just like the famous Voyager picture, seeing the Earth offset from the sun,” Morse explained, “but over two years’ time, we will see it move.”

Careful observation of that tiny moving pixel will tell us color, which tells us about atmosphere and surface chemistry; orbital characteristics, which tell us about volume, mass, and possible internal composition; other data may tell us about its temperature, the presence of moons or other objects, and so on.

It’s only possible because the telescope, floating in low-earth orbit, will be so specific to the task at hand. The satellite won’t be turning its attention to some other system afterwards. Of course, the first direct imagery of an Earth-like planet near a Sun-like star will be more than enough to justify the mission.

Project Blue is still far from a reality. It’s in the conceptual design phase — which, it bears mentioning, is different from concept phase for a product. In this case, it’s figuring out the exact parameters of the mission, from the size of the telescope mirror to the likely launch date and orbital path.

“We’ll have a mission development program which will look like a NASA Explorer mission, where you have Phase A, Phase B, Phase C/D, launch, then a Phase E science program,” said Morse. “We want to get Phase A going in 2017, so we can have a payload ready for launch by 2019, 2020. Then we’ll spend about two years intensively studying Alpha Centauri A and B looking for those planets.”

The cost the project, all inclusive, should be in the “tens of millions” — with a goal of $25 million. Compared to many a mission in the offing, that’s dirt cheap. Being able to hitch a ride on a commercial rocket helps, and the single-purpose design keeps costs down as well.

“We do need to find backers, all the way from possible crowdfunding to high net worth individuals,” Morse said. “But we also want to use in-kind contributions from partners, and perhaps could have the government as a partner.”

It’s ambitious, but then again, pretty much anything to do with space is. Expect more updates next year as Project Blue hammers out the details.