Everything is getting hacked to the point that it’s getting kind of ridiculous — and everyone needs to have secure passwords. The trouble, however, is making them tough to crack and also being able to remember them. That’s led to a blossoming ecosystem of password management services like OnePassword.

But if you ask Antoine Vincent Jebara and Priscilla Elora Sharuk, that’s not going far enough. Instead of locking those passwords away online and accessing them when you need to log in, their startup Myki looks to keep them locked away on your phone instead. Users can activate the Myki Chrome extension to log into various services through their phone, but the passwords are never kept on remote servers — and even administrators don’t know what they are once new passwords are issued. The company launched at TechCrunch Disrupt SF 2016.

“A big concern is the passwords are still in the cloud and people don’t want them to have access,” Jebara said. “Even when it comes to lawful access, in our case we don’t hold any sensitive info, which you can’t give away. We don’t want to have it, it’s your right to own and known where your proprietary data is.”

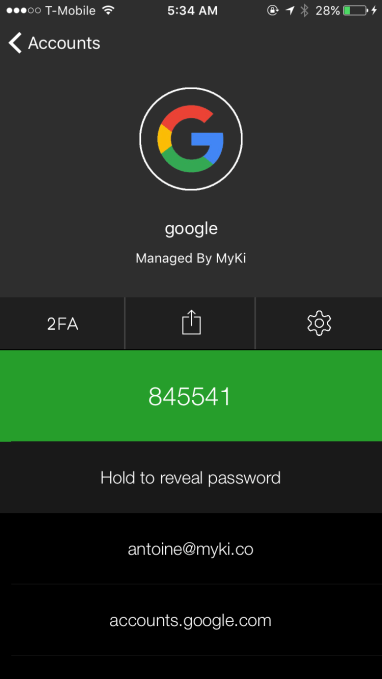

Here’s how it works: When a user decides to log into a service — it can be anything, really — they’ll choose to log in through Myki. They then authenticate that login on their phone through the Myki app, which is locked by fingerprint or PIN in addition to managed remotely, and the password and login is dropped into the browser.

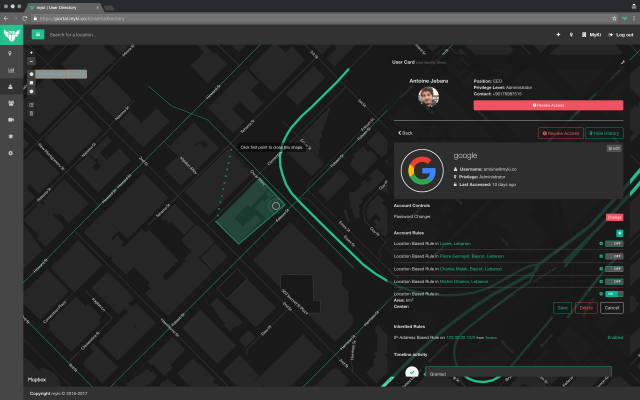

Through an administrative panel, users can authorize a variety of services, whether traditional browser logins or complex enterprise software, for login through Myki. The company generates passwords for those services that are then passed over to the phone and kept there instead of online. The passwords and login signals relay back and forth from the phone in order to log into various services, and administrators can assign passwords to be reset on a regular basis.

Myki is also constantly reporting back information about the logins. The administrative panel logs physical addresses, phone status (even battery level), IP addresses, geographic area, times and other kinds of irregular behavior, aiming to keep as many tabs on your password usage as possible. If something gets breached (through user fault or just a general hack) administrators can instantly trigger a mass reset, issuing new passwords to every user. Users operate the app using their phone number rather than typical credentials in an attempt to ensure that everything revolves around owning and operating a phone.

“What interests us is that the user is the owner of the phone,” Jebara said. “If GitHub gets breached, you need to do a mass reset of passwords — this takes time in the enterprise, and you have to pray for [users] not to change the password with only a slight variation.”

“What interests us is that the user is the owner of the phone,” Jebara said. “If GitHub gets breached, you need to do a mass reset of passwords — this takes time in the enterprise, and you have to pray for [users] not to change the password with only a slight variation.”

The goal here is to ensure that passwords remain complex, difficult to crack and easily accessible. Users have the option of looking at the passwords within the app (though an administrator can actually disable this, even though they don’t actually have access to the password), but they are designed to be kept on the device and away from remote servers that could potentially be breached.

The device control can be extremely granular, all the way to allowing only certain IP addresses (such as in the case of different floors on buildings of larger companies) or even locking geographic regions. That’s important to keep the right apps only being used at the right time and making sure everything is used in a secure environment.

Here’s another cool one: Users can actually share their login credentials with one another on a highly regulated basis. So if I need to give one of my colleagues a login to Getty or Shutterstock, for example, I can authorize them to use my account on a limited basis, and revoke that access at any time. Again, they’ll never see the password — that’s just for the account owner.

Right now, the company isn’t built into various mobile device management providers, but that’s another welcome opportunity, Jebara said. “We like the idea of bundling with MDM providers because they do root detection. If you root your phone that’s where we draw the line. If you use an MDM provider and push the key, they do root the detection, and we do access management, and it becomes more powerful.”

There’s always a risk for sticking all your passwords in one place. If your phone is compromised for some reason, like stolen by someone who somehow manages to crack the core iOS security and Myki, they’ll have access to everything to which you’ve given Myki access. To get around that — obviously use all the existing security features — Myki users can quickly revoke access to the device.

Right now the company is targeting companies as primary providers, but there’s obviously a consumer hook to it, as well. If users start relying on it for their traditional work login, they may want to tie in their Gmail and Facebook passwords — and IT managers won’t have access to that information, Jebara said.

There’s a reason all these password managers are reaching popularity — and companies are actively encouraging them. Often, user password behavior is pretty bad. They’ll re-use the same password for multiple accounts, the passwords won’t be strong, and they aren’t changed that often. That’s prompted a lot of breaches in the past several years, with hundreds of millions of credentials hitting the web.

With Myki, Jebara is hoping to take that level of security one step further, and make it even easier to log in and out of services. Time will tell if having everything locked away on your phone will work out in their favor — but it’s certainly something that Apple is trying to do, keeping a lot of operations on the phone instead of the cloud. The fewer the touch points where individuals can capture sensitive information, the better, Jebara said.