Apple’s head of security engineering and architecture, Ivan Krstic, told a rapt audience at the Black Hat security conference earlier this month that his notoriously secretive company was ready to open up its vulnerability reporting process to researchers.

Krstic announced that Apple was launching a bug bounty program, offering $50,000 for zero-day vulnerabilities that allow malicious code exploits in the kernel, among other rewards.

The thinking behind the bug bounty, according to Apple, is that discovering zero-day vulnerabilities — security problems that are unknown by a company but exploited by an attacker — has become more difficult as iOS security has advanced. Outside researchers could provide valuable assistance in discovering zero-days, and Apple wanted to start compensating them for their time.

On August 12, a week after Krstic’s announcement, Apple’s fears about an unknown vulnerability came true.

Ahmed Mansoor, an activist based in the United Arab Emirates, showed strange text messages he’d received to the human rights and technology organization Citizen Lab. The text messages contained a suspicious link, and analysis by Citizen Lab and the security firm Lookout determined that the link delivered a highly sophisticated packet of three zero-days that could take total control of Mansoor’s phone and spy on his calls, emails, text messages and contact lists.

The vulnerabilities show that hackers are increasingly turning their focus to mobile devices, and Apple’s increased focus on detecting zero-days shows that companies are striving to keep up. Mobile phones — particularly the iPhone — are often thought to be more secure than desktop computers and network infrastructure, so vulnerability research and hacking have been focused on those weaker devices. But the revelation of zero-days for Apple’s robust iOS security system marks a new era, in which the focus is heavily on mobile.

“To see three vulnerabilities, not just three vulnerabilities but three zero-days chained together to gain a one-click jailbreak is unprecedented,” Lookout’s vice president of security research and response Mike Murray told TechCrunch.

“A lot of people think mobile is a solved problem,” Murray added. “If I had said five years ago that committed attackers are attacking phones, you would have looked at me like I was crazy. The era of the highly-resourced attacker going after phones instead of network or desktop infrastructure has arrived.”

Our mobile phones now hold a wealth of information — and that information is drawing the attention of resourceful and sophisticated attackers.

‘An incredible level of sophistication’

Because of the three-pronged nature of the iOS exploit used to target Mansoor, Lookout researchers nicknamed it Trident. The exploit begins as a simple phishing attack, in which the hacker sends the target a link and entices him to click it. (In Mansoor’s case, the link came in a text message that offered him information about the torture of detainees.) The first zero-day was found in the iPhone’s default browser, Safari, where a memory corruption vulnerability allowed an attacker to run arbitrary code.

The texts sent to Mansoor.

Two kernel exploits are then downloaded to the device — the second and third zero-days of the set. The only indication of compromise that Mansoor would have received, had he clicked the link, is that Safari would have quit unexpectedly.

The first kernel exploit takes advantage of an information leak, allowing the attacker to locate the kernel in the device’s memory. In an iPhone, the kernel is a core component of the secure boot process — a security feature on which Apple prides itself. “Apple has done a good job of obfuscating where the kernel lives in memory,” Lookout’s Murray said. “For a jailbreak, you have to find the kernel.”

With the kernel located, the third zero-day is executed, giving the attacker read/write privileges. At this stage in the attack, the phone is jailbroken, and an attacker can add surveillance software to the device to collect information from Apple’s own apps and third-party apps.

Murray said the attack demonstrates “an incredible level of sophistication and commitment.”

“I don’t remember seeing many attackers at that level of professionalism and sophistication,” he added.

Murray’s team notified Apple of its findings on August 15. In the 10 days since Apple was notified of the security problems, it issued patches for all three. It’s a remarkably swift turnaround time for the security industry — many researchers will allow companies 90 days to patch a vulnerability before going public with their findings.

“We were made aware of this vulnerability and immediately fixed it with iOS 9.3.5,” an Apple spokesperson said. “We advise all of our customers to always download the latest version of iOS to protect themselves against potential security exploits.”

iOS users can download the patches by going to Settings > General > Software Update on their iPhones or iPads.

The NSO Group

Now that the sophisticated malware has been exposed, it’s natural to wonder who created it.

According to Citizen Lab’s analysis, the newly revealed vulnerabilities are the work of the Israel-based surveillance software developer NSO Group. The NSO Group appears to have marketed the vulnerabilities as a product called Pegasus. The company likely offers similar exploits for Android and Blackberry, and Lookout estimates that the iOS exploit has been available for purchase for roughly two years.

The company deliberately keeps a low profile and maintains little web presence. Founded in 2010, the NSO Group focuses its work exclusively on mobile exploits, according to Lookout’s research. Its founders, Niv Carmi, Shalev Hulio and Omri Lavie, sold the company to Francisco Partners in 2014 for $110 million, but still appear actively involved in running the business. The NSO Group sells its wares to government clients, including Panama and Mexico — and now, apparently, the UAE.

The NSO Group denied selling its exploits for unlawful purposes and tried to distance itself from the attempted hacking of Mansoor, the human rights activist, in a statement to Motherboard. “The agreements signed with the company’s customers require that the company’s products be used in a lawful manner. Specifically, the products may only be used for the prevention and investigation of crimes,” the NSO Group said. “The company has no knowledge of and cannot confirm the specific cases mentioned in your inquiry.”

Based on NSO Group earnings reports, Murray estimated that the zero-days Lookout uncovered could have been used on anywhere from 10,000 to 100,000 devices worldwide, but he stressed that it was just a back-of-the-napkin calculation.

“As far as I can tell, no one else has ever caught these guys before,” Murray said. “The product is committed to stealth.”

Busted

Now, the NSO Group is being forced out of the shadows, and three of its precious zero-days are burned (although similar exploits for major operating systems Blackberry and Android likely still exist in NSO’s toolkit). Lookout and Citizen Lab are already turning their attention to digging up more dirt on the NSO Group.

Now, the NSO Group is being forced out of the shadows, and three of its precious zero-days are burned (although similar exploits for major operating systems Blackberry and Android likely still exist in NSO’s toolkit). Lookout and Citizen Lab are already turning their attention to digging up more dirt on the NSO Group.

Citizen Lab published preliminary information on domain structures and command and control structures used by the NSO Group, and more information is sure to find its way into the public eye. Lookout is continuing its research into the malware used by the NSO Group and suggested it may publish more details soon.

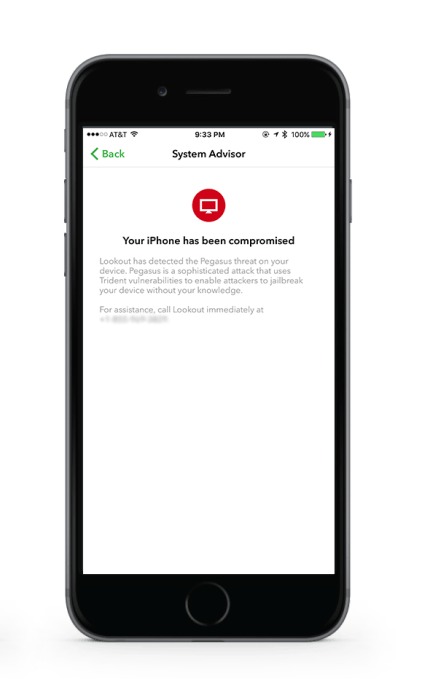

For now, Lookout is making it possible for iOS users to check if their devices were compromised. Users can download Lookout’s app, which is already installed on over 100 million phones, and scan their device for the NSO Group’s code. Murray encouraged journalists and others who believe they may be government targets to check their devices and call Lookout if they detect Trident.

“We want to catch these guys,” Murray said. “My goal is that you know what’s on your phone. If you click on a link and your life is owned forever, my goal is to make that stop happening.”

But while these zero-days are patched, they’re likely only one item on the NSO Group’s menu — and that’s why Apple is pushing harder than ever to find its vulnerabilities before the NSO Group or other mobile specialists do.