Theranos has had a long 10 months. The company, beset with regulation issues, has faced a Congressional inquiry, possible criminal charges, lawsuits, a recall of test results from the past two years, its main partner Walgreens severing ties, Forbes downgrading its worth from $9 billion to now just under $800 million, and its founder Elizabeth Holmes was formally banned from operating her own laboratories for the next two years.

So it was in this dark night of despair that Holmes told members of the media and the science community she would finally be opening up about Edison, her one-drop blood analysis technology 11 years in the making. Hundreds of scientists lined up at the American Association for Clinical Chemistry this week in the hopes of finally getting a behind-the-scenes look at the secret machine. Instead, they got an introduction to an entirely new product — an all-in-one Zika-detecting tabletop miniLab.

According to Holmes, the miniLab can run a number of automated tests using blood and urine samples, including one she claimed is a first-of-its-kind for detecting Zika. Those tests are then uploaded through a centralized system that can collect samples, process the data and dispense results.

Holmes told audience members that the plan was to fast-track the device through FDA approval under the newly issued emergency use authorization (EUA) for Zika detectors.

It’s a strategic move for the company. Zika has struck fear within the U.S. health community, especially after 14 people in a Miami neighborhood were recently diagnosed with the primarily mosquito-transmitted illness. Zika is often asymptomatic or causes a mild rash, fever and joint pain. But the bigger concern is what the virus can do to pregnant women. Zika has been linked to microencephaly in infants born to mothers with the disease.

However, detection is tough, and with a lack of any commercially available diagnostic tests cleared or approved by the FDA for Zika at the moment, the virus is spreading rapidly throughout many parts of the Western hemisphere. The FDA has said it would be fast-tracking certain Zika detection tools under EUA for that reason — something Theranos clearly hopes to take advantage of.

Will Theranos’s new miniLab be enough to save the company from itself?

Recycling material

Theranos seems to have pivoted away from a previous lab testing facility model and is moving into field collection via the new miniLab. But according to several clinical lab scientists with whom TechCrunch spoke to, there’s not anything novel about Theranos’s new product — at least nothing detectable from Holmes’s presentation.

“It left a lot of us dissatisfied. It was kind of a letdown,” University of Chicago’s Jerry Yeo said of the new miniLab. “It doesn’t even have the routine immunoassay and didn’t show how sensitive it was.”

Professor of clinical and lab pathology at Weill Cornell Medical College Stephen Master, who was in the audience at Holmes’s presentation along with Yeo, agreed. “It wasn’t like there was anything fundamentally we hadn’t seen before,” he told TechCrunch.

To be fair, Theranos’s previous mishaps likely jaded much of the scientific community before Holmes took to the stage.

But to Master’s point, there are several companies with “lab-on-a-chip” technology, which Theranos maintains is not what its box is, but does have elements of.

Qualcomm’s Tricorder X-Prize searches for similar companies with the idea of revolutionizing healthcare by placing an accessible lab in the field. The organization offers millions of dollars to companies that can come up with automatic non-invasive health diagnostics packaged into a single portable device. The concept is exactly what Theranos wants to do with the miniLab.

Zika bytes

The new product is also not much different than other Zika-detection prototypes out there – some of which are already listed on the FDA’s website.

Zika detection devices actually seemed to be a trend at AACC’s event this week. John McDevitt from the NYU college of dentistry also presented a device that Master thought sounded pretty much exactly like what Theranos proposed.

“I swear his first five minutes were almost identical to Theranos in terms of the box look, in terms of the slides, some of the pieces that were actually inside. It was another integrated analyzer like that,” Master said.

The difference is McDevitt’s programmable bio-nano-chip, which Master referred to, has been peer reviewed – something the miniLab has yet to do but will likely need if it wants FDA approval.

There were other Zika detectors presented at the conference, as well. One promising device was developed in collaboration with MIT, Harvard, University of Toronto and Cornell University.

It’s unclear how likely, given Theranos’s reputation, the FDA will approve its miniLab, even under fear of Zika. We’ve reached out to the FDA but have not heard back.

But we should note Zika is not the first disease Theranos has used to drum up support within the government for its technology. The company sought FDA approval for early Ebola detection last year, devoting a large chunk of time and resources to its test for the highly contagious and deadly disease.

“We stopped everything for Ebola — for the world,” Theranos exec Richard Kovacevich told the New York Times in 2015. But focus on the disease seemed to fizzle out and Theranos moved on, saying FDA approval for the test was no longer something the company was pursuing. Would the same thing happen if it doesn’t get approval under EUA for Zika?

It also seems quite expensive and makes little sense for Theranos, once a lab operation with dozens of testing facilities inside Walgreens, to switch into manufacturing. Yeo, who has looked into similar operations in the past repeated those concerns to us — but the move may be the result of Holmes’ recent ban from operating her own labs.

So what happened to the old tech? Theranos left a room full of skeptical scientists wanting, barely mentioning the data it has likely gathered over the last decade from its technology. TechCrunch reached out to Theranos to ask about its proprietary Edison technology and how much of it was applied to the new miniLab.

“Edison is the name of one early iteration of this technology,” a spokesperson for Theranos told TechCrunch. “The miniLab is the latest iteration of the company’s testing platform and an evolution of Theranos’s technology.”

We were promised hundreds of tests on a single drop of blood and all we got was this box

Theranos’s tabletop lab is not exactly revolutionary; dozens of companies have made miniature lab-testing devices. And though the company told TechCrunch it has not “worked on a lab-on-a-chip system for some time,” this is, essentially, according to all the experts we spoke to, the same idea. Except it’s a box.

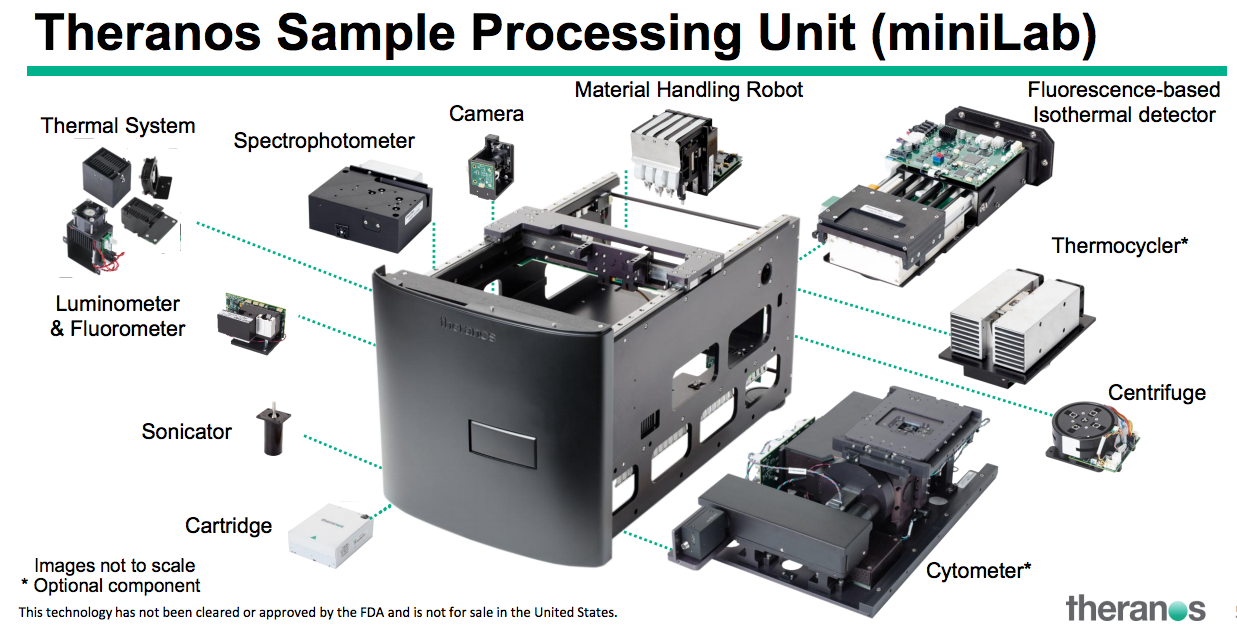

The miniLab is composed of parts that collect small samples of blood and urine to automatically process and upload to a centralized system. It doesn’t process hundreds of lab tests on a single drop of blood, as previously promised.

Holmes showed data from 11 tests in her presentation but says it can run up to 40 tests. However, Yeo told us there would need to be several samples of blood and multiple finger pricks to run these tests, not just one drop of blood for dozens of tests — a far cry from Holmes’s story of getting into this business to make blood testing quick, easy and painless.

“The reality was the reason everyone was in that room [at the conference] was because they made these really broad claims about what their technology was going to be able to do,” Master said. “The excitement was how in the world are they doing that…Instead what they ended up showing was some of the general performance and classes of tests but they never came close to really addressing those larger capabilities that they had talked about.”.

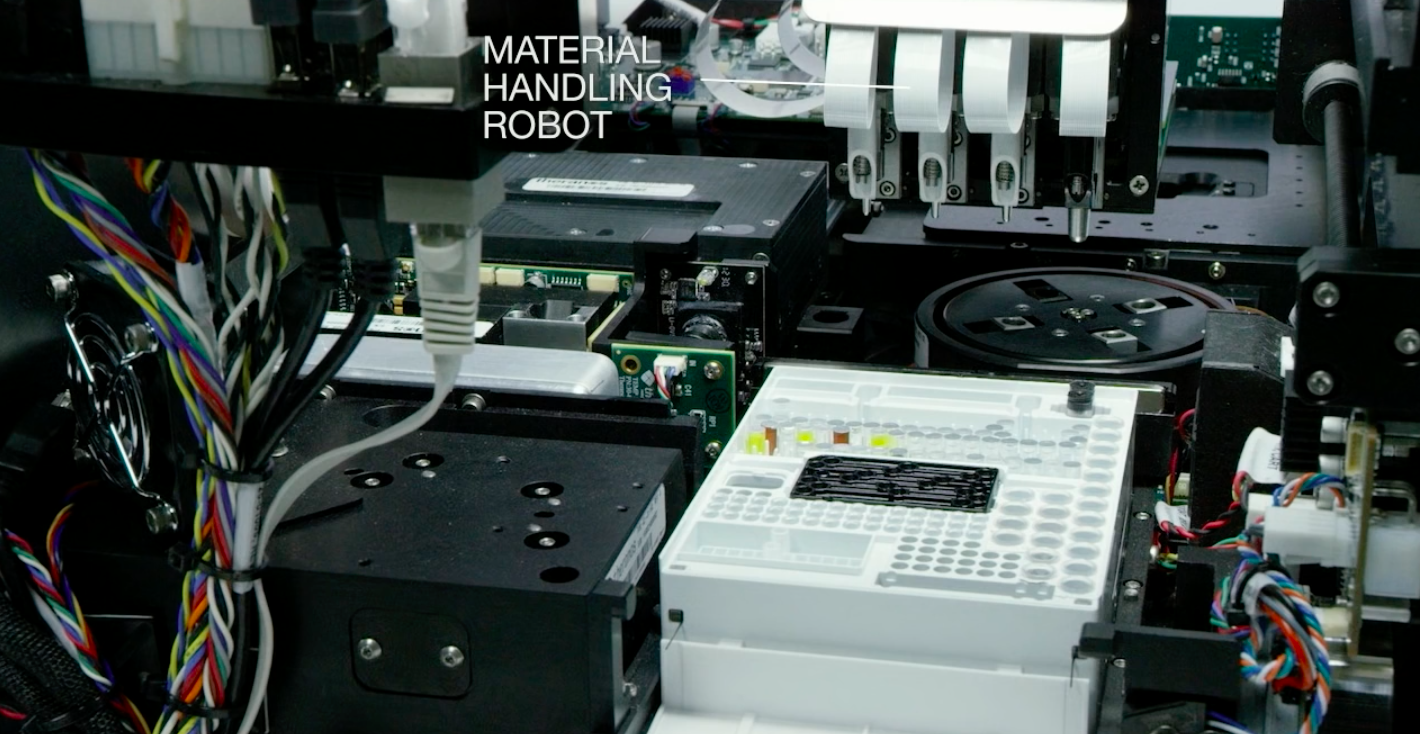

The key here may be in the automation of lab tests in the field. You’ll see different components in the illustration above of the box from Holmes’ presentation. The founder laid out how her capillary blood collection devices, including the proprietary Nanotainer tubes and Sample Collection Device (SCD) would collect the samples and be inserted into the box to process.

She also outlined the Theranos Virtual Analyzer (TVA), a remote communications software system that could upload results to a lab.

“The miniLab architecture provides a potential framework for testing in a decentralized setting while maintaining centralized oversight,” Holmes told the audience.

Something like that could be applied in the field, like say in a Zika-infested area, but both Master and Yeo emphasized the difficulty in conducting lab testing in an uncontrolled field environment.

“As soon as you start going out into the wild, as it were, into doctor’s offices and different settings, it’s going to be difficult to maintain,” Master said.

It’s also unclear if the miniLab will be fast-tracked to go out into the wild, given the company’s background and current lack of third-party, independent research.

Theranos told TechCrunch it considers its own Zika test as its clinical trial, per FDA guidance. Compare that approach with other device makers like Scanadu, which is in the process of seeking permission from the FDA for its Scout device, partnering with Scripps to conduct a 4,000-person clinical trial to get it there.

However, Holmes did mention during her presentation the company would be publishing the findings from its technology in peer-reviewed journals and conducting third-party studies, indicating Theranos would be subjecting itself to independent scrutiny in the future. But, added Holmes, that “will not happen in one day and one presentation.”

And maybe Theranos is starting to understand how to operate. It’s added a medical advisory board, hired clinical lab experts to key positions, says it wants to be more transparent in the future and, as mentioned, says it is willing to publish in peer-reviewed journals — something it has been roundly criticized for not doing in the past.

Is the box enough to help it regain credibility in the medical community? Who knows. Those in attendance expected to hear about the technology that could produce hundreds of lab tests on a single drop of blood and all it got was this box. From what we’ve gathered the scientific community doesn’t seem overly impressed.

Theranos has an uphill battle ahead to prove itself to these scientists, government regulators and consumers. But one thing is clear, past the jargon and pomp, Theranos is more of an evolution, not a revolution so far.