As the graphics in games and movies edge closer and closer to photorealism, even the subtlest tricks of the light must be simulated. For years an especially tough one has been recreating the sparkling, uneven surfaces of water, metals and other materials — but these glints can now be rendered 100 times faster than before thanks to a new technique from computer scientists at UC San Diego.

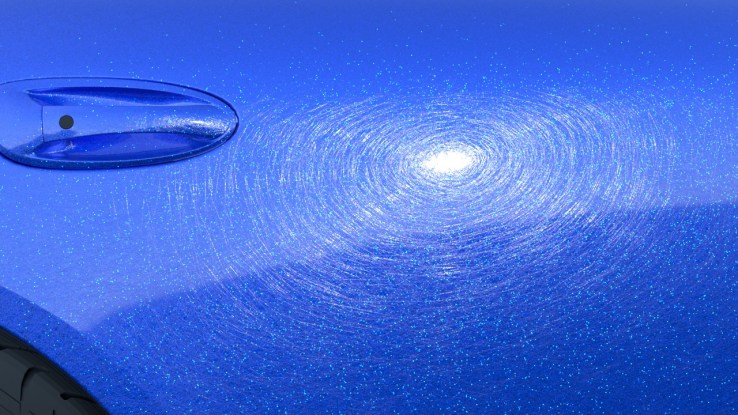

The problem with rendering these specular highlights, as they’re called, is that they’re just so complicated. Up close, a surface is rarely totally smooth, but rather is covered in microscopic bumps and scratches — and light hitting that surface is scattered all over the place, producing the glittering spots and lines that are so familiar to us.

Nature, of course, has no problem rendering where the light goes, but a computer must perform thousands or millions of calculations to create an accurate simulation. There are shortcuts and ways to fake it, but no real solution.

“There is currently no algorithm that can efficiently render the rough appearance of real specular surfaces,” said UCSD’s Ravi Ramamoorthi in a news release. “This is highly unusual in modern computer graphics, where almost any other scene can be rendered given enough computing power.”

Using the technique to render all those little scratches only took 1.4x as long as rendering it totally smooth.

Ramamoorthi and his colleagues took an unusual path in computer graphics: simulating the phenomenon at an even lower level. Each pixel making up one of these uneven surfaces is considered as a multitude of light-reflecting “microfacets.” Some clever math allows the system to determine which microfacets will reflect light toward the virtual viewer, then generalize that information among similar microfacets according to a normal distribution.

Using this “position-normal distribution” technique produces a highly accurate representation of speculars — and because the renderer is spared the trouble of checking how every ray of light interacts with every tiny scratch or bump, it’s far faster as well.

Two more samples of the kind of lighting and features this new technique renders so efficiently:

The researchers are presenting their work at SIGGRAPH next week, but you can read the full (rather technical paper) here.