It’s been four decades since the Viking 1 lander touched down on Martian soil, the first lasting human presence on the surface of the Red Planet. It beamed its unprecedented data back to NASA, where it was stored on the hot new format of the day: microfilm. Now one scientist wants to bring these analog records into the digital world — for posterity and for science.

“I remember getting to hold the microfilm in my hand for the first time and thinking, ‘We did this incredible experiment and this is it, this is all that’s left,'” said David Williams, a scientist at Goddard Space Flight Center’s archives in Maryland, in a NASA blog post. “If something were to happen to it, we would lose it forever.”

Many of us have surely felt the same way about a shoebox full of 3x5s, and we likely had the same instinct: get this stuff saved digitally ASAP.

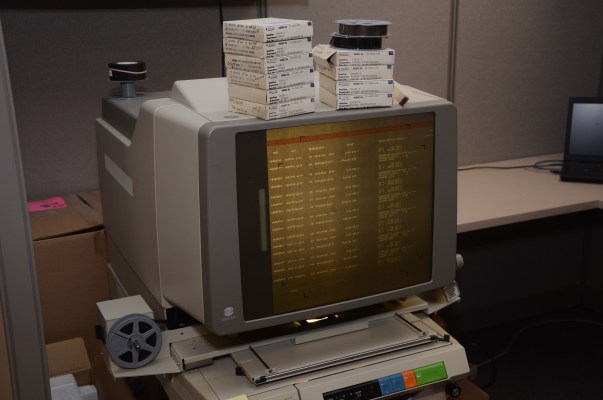

So that’s what his team started doing: digitizing the rolls one by one using the microfilm reader — a device old school library users will remember, perhaps not entirely fondly. The process of getting the information you want is pretty involved.

It’s not just a sentimental gesture, though: missions to the surface of other planets aren’t exactly thick on the ground, and data from them stay relevant more or less forever. Williams had only looked for the microfilms, in fact, because a biologist had requested the data from them in order to look into certain hypotheses.

“All the biology data was only on microfilm,” wrote Williams in an email to TechCrunch. “The microfilm was a copy of a computer printout, it was a combination of tables of numbers and text and numbers combined. Each frame was one page of printout, about 30 to 40 lines. We scanned all the frames, and for the labeled release we ended up typing the numbers in by hand.”

Current missions like Curiosity and the upcoming Mars 2020 rover will also want to compare their data with Viking 1’s and all the rest — after all, changes over decades could indicate interesting processes occurring in the soil or atmosphere, which in turn could suggest the presence (or absence) of life, among other things.

“The capabilities of the Viking landers and instruments were very advanced for the technology at the time,” explained another Goddard scientist, Danny Glavin. “Viking data are still being utilized 40 years later. The point is for the community to have access to this data so that scientists 50 years from now can go back and look at it.”

Because I’m curious about the process of digitizing all this cool old analog media, I’ve asked NASA for more details. I’ll update this post when I hear back.