How far can the Pokémon brand carry Pokémon Go? Will its popularity fade after that initial burst of activity thanks to the power of its brand?

That’s a huge question that’s circulating now that the game has immediately popped to the top of the App Store and has cemented itself as one of the most successful game launches of all time. The mechanics of the game are fundamentally sound, and it has an extensive library of nostalgic content and a unique real-world experience that spans multiple demographics that should for the time being continue actively bringing in new players. But can it keep that up?

Dan Porter, the former head of OMGPOP and one of my favorite game managers out there, lays out a good argument for why Pokémon Go could be a bang-and-fizzle. Already Pokémon Go has the makings of a cultural zeitgeist, tapping into nearly a decade of pent-up demand for a smartphone version of Pokémon. But it may lack some of the core elements — like strong user-generated content and a sharp difficulty curve after the initial ramp — that can sustain the game’s playability beyond just rapidly progressing through early content.

I think pegging Pokémon Go as a potential bang-and-fizzle game right away might not be giving the game (or its developers) enough credit. I think if the game’s existing mechanics can’t sustain an extended player life already, then it has so much overhead that its brand can very easily carry it until future, more traditional user-generated content features come out. I’d also argue there are early elements of user-generated content already built into the game. There’s a challenge of avoiding feature-creeping the game to death, but it seems like the team has shown it has the developmental chops to build a really good game.

This feels a bit like a too-soon question. We haven’t seen where the game’s development and iteration is going to go. That being said, Dan has a lot of great points in his post. I have a few I’d like to add here for the general argument on the internet happening:

- I think the Minecraft analogue between user-generated gameplay (UGP) and user-generated content (UGC) here is the difference between jumping into a session and building versus encountering something new that’s already built or with an existing structured community. Minecraft does a really good job of both of these, which is what I’d argue is its biggest contributor to its staying power.

-

- Good UGC is a precursor to good UGP. In order to create a fun, unique playing session, the creator of the game has to have good tools for producing UGC that leads to good UGP, or create the content themselves that can facilitate a good UGP experience. Each playing session is a unique experience, giving players a reason to come back over and over again — even if it’s for the same level.

- Candy Crush Saga, meanwhile, doesn’t have UGC. Its core, reliable mechanic is fresh UGP, which is something that can carry a game for a very long time as long as there’s good content. But in the case of Candy Crush Saga, that can also turn into a race against time to create enough content that keeps players engaged. I’d argue what Candy Crush Saga (and also Kim Kardashian: Hollywood, which we’ll get to later) excelled at was building a strong casual user base that progressed through the game at a more leisurely pace.

- The argument that there is no strong UGC in Pokémon Go I think is not giving the game enough credit. It’s the personality and quirks of a new player in the real world. Are they an ass? Are they nice enough to point out where a Pokémon is hiding? This has an opportunity to not only establish new social connections, but enhance existing ones (in the case of a 22,000-strong Pokémon Go crawl scheduled for this week). That’s all dependent on the user, and isn’t content that’s created by Niantic, though the company gave players the tools to do that.

- The amount of UGC for Pokémon Go in this case is a product of the number of users and the density of those users in a geographic area. This works for and against Niantic and Pokémon Go. It means the game is going to be a very good and sticky experience in high-density locations like cities, but in remote areas or less dense metropolitan areas there’s simply going to be less UGC for now. Niantic is going to have to figure out how to build in some elements of UGC for The Rest Of Us or end up in a content race to keep that player base engaged like Candy Crush Saga or Kim Kardashian: Hollywood.

- Pokémon Go seems to do a really good job of adding an element of randomness to the capture experience that should keep the player opening the app and not feeling like they have to go on a difficult three-mile hunt for a Charizard. For example, one of my colleagues (who will remain nameless for now) was walking to Caltrain and a rare Pokémon randomly popped up, much to the delight of other players around him.

- The gym component is still a question mark, and it’s on Niantic to make that a lightweight experience that keeps players from becoming too powerful, too quickly. Locking out end-game content is a classic problem for massive progression-based games. The notion in a lot of MMOs is that new end-game content for games like World of Warcraft and Destiny is built for hardcore users. Then the rest of the end-game content gradually becomes easier and more accessible. Pokémon Go is a different situation — it has to continue catering to the broadest audience if it wants to be something big and sustainable like Minecraft.

- What often goes overlooked is that Candy Crush Saga did a phenomenal job of building a strong, satisfying difficulty and progression curve by producing levels with differential difficulty. This is called “sawtooth tuning”: You would encounter easy levels, then increasingly hard ones, which would then be followed by easier levels. It’s the satisfaction of solving a really difficult puzzle, and then bringing the adrenaline down and letting the player relax a bit and ramp up again. Pokémon Go does this somewhat by varying the difficulty of capturing Pokémon and gym battles — for now.

Despite Pokémon Go being already very highly polished from a mechanical standpoint, the game still actually feels a little half-baked (or, at least, three-quarter baked). It’s missing many elements of the core Pokémon experience, like trading. While that, for example, has the potential of cannibalizing the walking experience to gather new Pokémon (a strong element of UGP in the game), it also offers a unique opportunity for players to build a stronger social graph that piggybacks on other communication channels (real world, WhatsApp, Facebook, Craigslist, etc). That social graph doesn’t necessarily have to exist within a game if the UGC and UGP of the game is strong enough.

There’s a ton of opportunity for additional UGC for Pokémon Go. The one I’d first point to would be team composition at gyms. Facing off against a unique team of Pokémon with a unique set of moves requires a level of adaptation and improvisation much like entering into another player’s Minecraft universe and having to understand its structure very quickly in order to better participate. When you play the original Pokémon for the first time, you have little knowledge of what to expect in a gym other than that it generally relies on a certain element. You can prepare somewhat, but you’re also restricted to the resources you have, so you have to basically improvise and hope for the best — or try again when you lose. Now, imagine this happening in every gym encounter you ever have in Pokémon Go.

The same could be said of trading. Encountering a player open to trading again has an element of randomness to it. Different players open to trading, in theory, should have different Pokémon. So once again a player has to improvise and negotiate a trade for a Pokémon if it’s one they have a strong desire to obtain. That player has to deal with a new personality and a new set of expectations when setting up the trade.

Both of these help contribute to the staying power of Pokémon on Nintendo’s devices. Users are faced with an onslaught of UGC once they clear out the main storyline and gather their own set of Pokémon as they start battling and trading with other players. The battle is a strong UGP experience, but the opponent’s experience and team composition is also a strong UGC experience. The competitive elements might not be particularly palatable for casual users, but, nonetheless, it’s a big well of potential UGC and UGP to keep people engaged for the years that span a development cycle of a Pokémon game.

The intent of the developers here seems to be that they do not want to go the route of focusing just on content to extend the life of the game, but rather try to bake in additional UGC mechanics. They could always add more Pokémon, but that doesn’t address the problem of users racing to the end of the game and finding themselves with nothing left to do. The makers of Candy Crush Saga were great at pumping out new content, but eventually your player base will catch up and lose interest.

I understand the necessity of keeping the features to a bare minimum. Very rarely are applications released in a complete form that never iterates. Even the most-polished games like World of Warcraft and Minecraft are in a state of constant flux, with new content and balance changes regularly coming out. It’s important to ensure that the experience feels like Pokémon, but is best suited for mobile devices.

So! All that said, for now let’s assume Pokémon Go already is where it’s going to be in the next year. Does that mean it has to entirely rely on its brand in order to keep it rolling, and how far can that carry it?

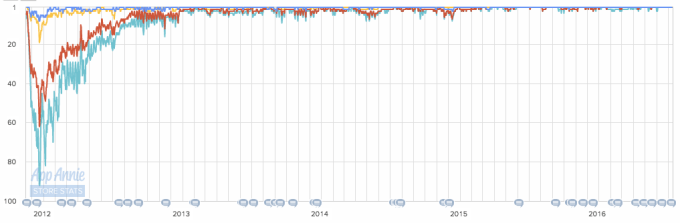

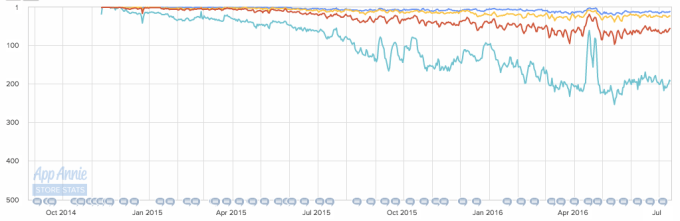

Let’s take a look at different cases of games that have been carried by brand equity at their launch. The first case we’ll look at is Minecraft: Pocket edition. This, like Pokémon Go, really nailed pretty much every aspect of the game development process. But it also had years of built-in brand equity among a very diverse set of demographics. To be sure, that starting base was definitely way smaller than Pokémon. But nonetheless, here are the charts:

Top Paid Downloads (wow!)

Top Grossing

So we can see here that it actually took a while for Minecraft to really ramp up, despite having some brand equity built up. But what we can see from this sustained top grossing status is that it’s constantly attracting new players (because it’s a paid app) despite the lack of an internal social graph. The only incentive to getting a new player into the game is really to add someone new to play with, and you really have to hunt someone down to accomplish that. What Minecraft does really well is have the baked-in tools to inspire really strong UGP and UGC. It’s an augmented Lego experience, after all.

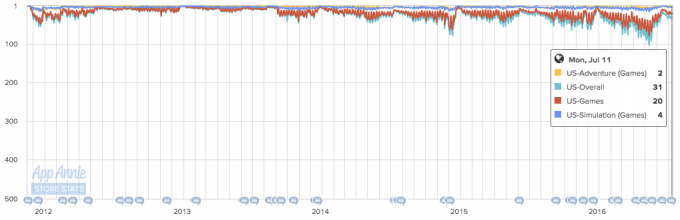

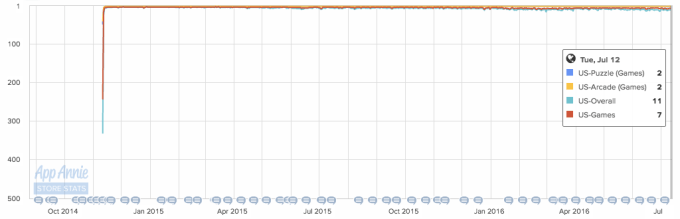

So let’s look at a different, maybe more unique case. Kim Kardashian: Hollywood also represented a huge, untapped cultural zeitgeist that had yet to make its way into a mobile game. Then it came out with a bang and blew away most (all?) other games in the App Store. The charts:

Top Free Rankings

Top Grossing (wow!)

So this is another case that’s a little perpendicular to Minecraft. Kim Kardashian: Hollywood had a very strong set of tools for UGP. But what the game was really about was a lot of strong content that kept players compelled. The tricky part about that is producing enough content becomes a race against time to keep players engaged and not deleting the app. This led to a really powerful start, but it couldn’t sustain the momentum and eventually tapered off. We’re probably going to see something when a game about Taylor Swift or Kanye West comes out.

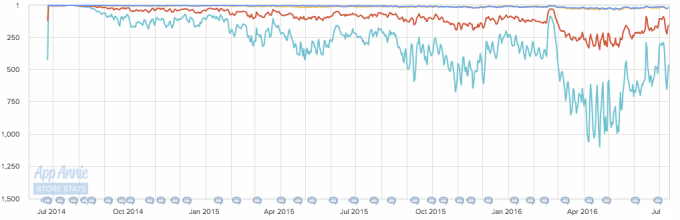

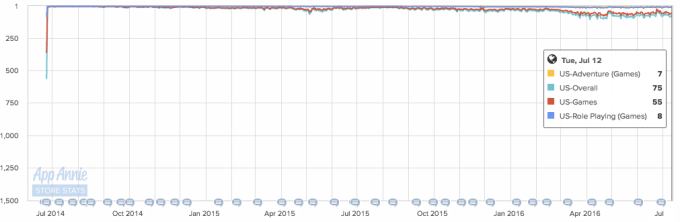

A quick, but similar case before moving forward — let’s take a look at Candy Crush: Soda Saga, because it is probably the closest comparable given that it’s piggybacking off existing brand equity.

Top Free Downloads (this looks familiar…)

Top Grossing (also familiar!)

The lesson from Kim Kardashian: Hollywood and Candy Crush: Soda Saga is really that brand equity can only carry you for so long, but holy hell does it give you a head start. That’s important for attracting a core “whale” user base that’s going to sustain the life of your game. And, lining up with Dan’s point as well, just glancing at the top grossing charts means you don’t have to sustain a constant flow of new players in order to be a successful game from a revenue standpoint. These games are clearly monetizing well for years.

So, here’s the rub: If you want to see a success like Minecraft, it’s clear you need both strong UGC and strong UGP. If you have good UGP and an accompanying social graph but lack in UGC, you probably built a highly monetizable game — and a potential cultural zeitgeist — that might not have the long shelf life of a game like Minecraft. If you have the brand to give you a boost, it buys you the room to figure out how to build in strong UGC. And Pokémon Go, which already has pieces of UGC in place, has that window to build stronger and more long-lasting tools.

Before closing, I’d like to address the Words with Friends or Chess with Friends comparisons. While these also have strong elements of UGP and UGC, I’d argue that the playground for these games simply didn’t have the strong infrastructure to trigger that moment of inspiration in really casual players that progresses them toward the finish line. These kinds of games might be really fun for creative or well-trained individuals, but the early curve was a little sharp in order to make the game really fun to a huge audience without the patience to achieve that mastery without any guidance. If a player isn’t progressing — especially for games that aren’t obviously showing how the player is growing in skill or practice — then it might lead to some burnout outside the most devoted players.

In the case of Pokémon Go and Minecraft, the depth of initial content is so structured that players don’t have to be grandmasters of Pokémon and Minecraft to have a really fun experience. They can just screw around with the entry-level content until they pick up the basics and not be restricted by the immediate stringent goals of games like Chess or Scrabble. Playing the same player over and over again also gives users an understanding of how the other player thinks, which kind of removes the potential of seeing brand new strategies that require extensive improvisation. There’s a massive universe of player-created content already available in Minecraft that’s a product of the number of active Minecraft users, and that’s how Pokémon Go should be moving.

Having an explicit, smooth mastery and progression curve — and initial ramp — is critical to a long-lasting game, and in cases like Chess or Scrabble players may be paralyzed by the options and not know which move to make. They might also not know what the rate of their progression is, or how to gauge the “level” of their opponent. Match-3 is great for this because it’s more of a compulsive mechanic that feels very natural and tuning level difficulty is a little more straightforward. To be truly great at Chess or Scrabble, you pretty much have to study (online or other players) or have a dictionary out with you (which is totally cheating).

Worst case scenario, as Dan suggests, is that it has a core devoted user base in cities that’s highly monetizable. There’s a good chance it’s already attracted the whales it needs to actively sustain itself. End of the day, I’m long Pokémon Go.